Paige Pagnucco

Director, Forest Service Utah Avalanche Center

If you’ve been following the avalanche forecast this season, you’ve noted that Utah, and much of the Intermountain West, is dealing with a persistent weak layer avalanche problem that has been producing large, destructive avalanches. Tragically, some of these have been deadly. You’ve probably also heard a common trend among avalanche forecasters advising backcountry riders to avoid “thin and rocky areas, where you are more likely to trigger an avalanche.” In this blog post, we will discuss what’s going on with persistent weak layer avalanches and why thin spots are so dangerous.

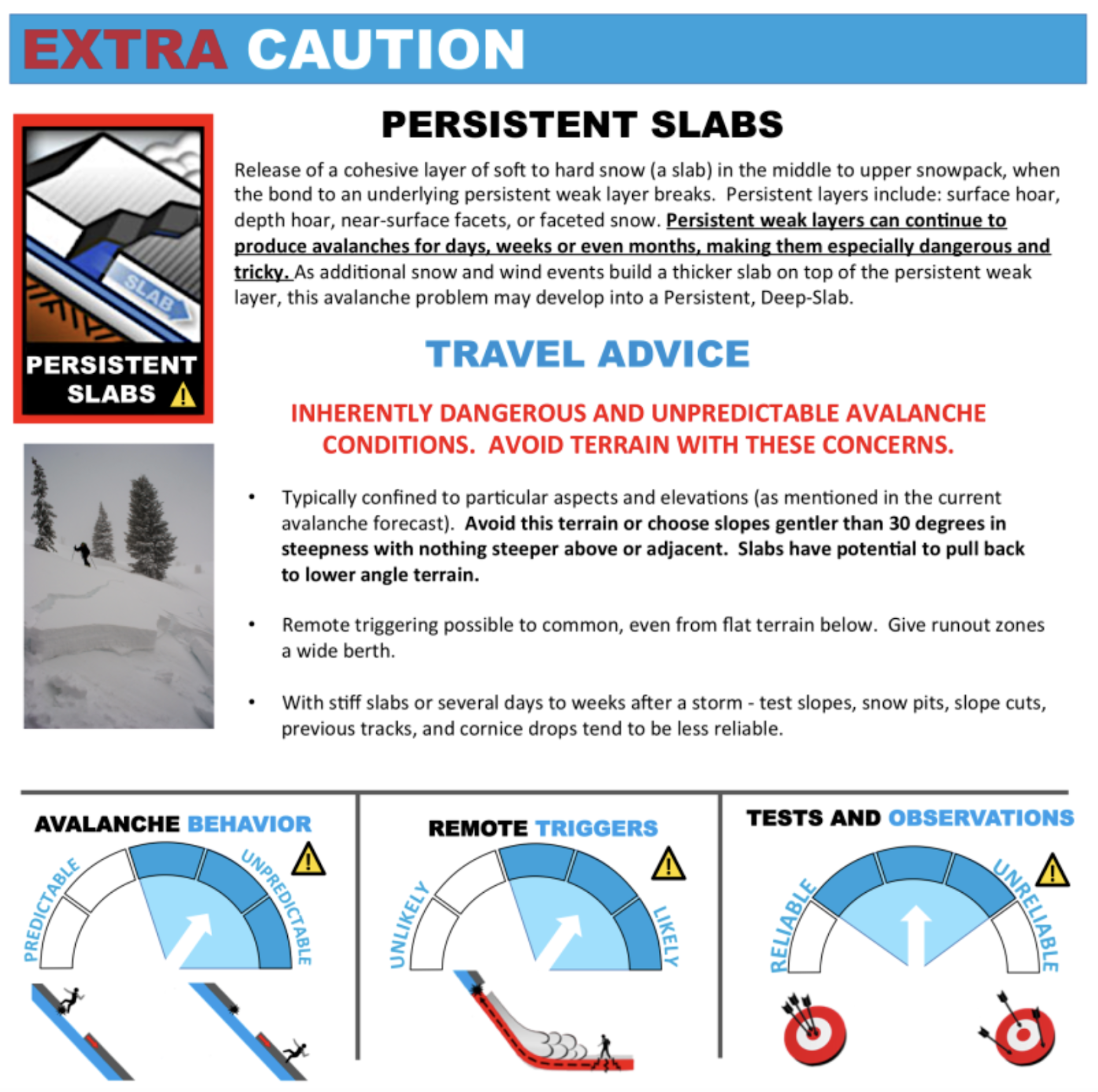

Before diving into the post, it’s worth noting the "Persistent Weak Layer" term used by the Utah Avalanche Center encompasses what other forecast centers refer to as "Persistent Slab" or "Deep Slab" avalanche problems.

Understanding the Risk of Persistent Weak Layer Avalanches

Avalanches involving a Persistent Weak Layer (PWL) are particularly dangerous because the weak layers can remain active for extended periods, even long after the snowstorm that initially created them. These avalanches are often triggered from locations where the slab above is thin, sometimes in spots that are hard to identify. The risk remains as conditions persist, making it essential to understand how these avalanches form and how to manage them.

How Persistent Weak Layers Form

Persistent weak layers form over uneven terrain, like rocky areas, where snow accumulates unevenly. While snowfall and wind smooths the surface, weak layers such as facets (or sugary snow) often develop beneath, especially in calm, cold conditions. These layers can remain active for days or even weeks, waiting for a trigger. Even though the surface may appear smooth, the persistent weak layer still lurks beneath, making these areas prone to triggering when stress is applied.

This example snowpit clearly illustrates a stronger slab (1F to 4F) sitting atop weak snow (F), the persistent weak layer. A classic poor structure snowpack. You’d likely get easy results in an extended column test, propagating at the interface between the facets and the slab.

The pit profile above is from a fatal PWL avalanche that occurred on New Years Eve. You can easily see the snowpack has low density snow capped by higher density snow.

When snow falls early in the season, it is a magical time for most people. For avalanche forecasters, it is the beginning of what could be a long, drawn-out problem with buried weak snow. When the shallow snow is exposed to many nights of clear, cold weather, it begins to facet. The grain shape becomes angular (see photo below), and the consistency of the snow is like rock salt—not great for snowman building.

The Danger of Triggering an Avalanche on a Persistent Weak Layer

The danger with persistent weak layer avalanches is they can be triggered far away from their weak spots, often by a skier, snowboarder, or snowmobiler unaware of the instability beneath. The avalanche may not release immediately, but once it starts, the crack propagates along the weak layer, spreading across the slope. If the skier or rider is unlucky enough to be on the wrong part of the slope, a massive avalanche could be triggered, potentially with deadly consequences.

Even when tracks are already visible on a slope, it doesn’t mean the risk is gone. The first person may not trigger the avalanche, but the second or third or tenth person could. Persistent weak layers can be tricky, and the stress from a person or snowmobile may be enough to cause a fracture if the slab is thin in certain spots.

This accident on Christmas Eve could have had a much worse outcome were it not for the partner’s avalanche rescue training. The buried person’s fingers barely poked out of the snow when his partner used his transceiver to hone in on his location. Luckily, he was buried with his head about 1-2 feet under the snow. Unfortunately, he broke his leg.

It should also be noted that roughly 70% of our avalanche fatalities involved avalanches failing on a persistent weak layer.

Identifying Persistent Weak Layers

So, how do you know if you're dealing with a persistent weak layer problem? Avalanche forecasts often indicate whether persistent weak layer avalanches are a concern, as they can form after significant snowfall, especially in areas with wind-loading. Terrain features like scoured areas, wind pillows, or exposed rocks can indicate where the snowpack is uneven and the slab may be thinner.

Probing the snow can sometimes reveal variations in snowpack depth, signaling possible areas of weakness. It’s important to remember that these layers may not always be obvious, and sometimes, it’s difficult to assess whether the snowpack has thin spots where an avalanche could be triggered. Get out your shovel and dig in a safe place to look for weak snow. Slopes with untouched snow can be tempting, but with a buried weak layer, they can also be booby traps.

This avalanche in Butler Basin on January 12 was triggered by the third skier who presumably hit a shallow spot on the slab. You can see rocks near the crown in two places, both right below some trees. Facets love to grow and stay weak around rocks. The skier was mostly buried and was luckily successfully rescued by his partners.

Managing the Risk

When the avalanche danger with a PWL has dropped to MODERATE, the consequences of triggering one of these avalanches are still very real. The size and magnitude of the avalanche is the same, it’s just that the “likelihood” of triggering has gone down. Using terrain management skills to reduce exposure to these areas is essential. Avoid slopes with visible wind effects, rocks, or other signs of snowpack instability. Complex terrain with uneven snow distribution should be treated cautiously, and it may be wise to opt for simpler, lower-risk routes.

In the field, constantly reassess the snow conditions and be prepared to change course if the risk feels too high. As experienced avalanche professionals often say, the more complex the avalanche situation, the simpler your terrain choices need to be. If in doubt, it’s always better to err on the side of caution.

When the avalanche danger with a PWL has dropped to MODERATE, the consequences of triggering one of these avalanches are still very real. The size and magnitude of the avalanche is the same, it’s just that the “likelihood” of triggering has gone down. Using terrain management skills to reduce exposure to these areas is essential. Avoid slopes with visible wind effects, rocks, or other signs of snowpack instability. Complex terrain with uneven snow distribution should be treated cautiously, and it may be wise to opt for simpler, lower-risk routes.

In the field, constantly reassess the snow conditions and be prepared to change course if the risk feels too high. As experienced avalanche professionals often say, the more complex the avalanche situation, the simpler your terrain choices need to be. If in doubt, it’s always better to err on the side of caution.

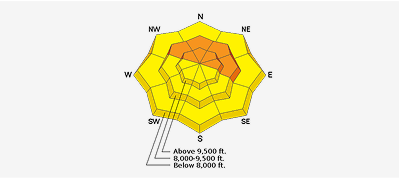

It’s critical to keep track of where buried weak snow exists. It usually lives on slopes on the cold, shady north half of the compass at mid and upper elevations. The heat map above shows the aspects and elevations where all Persistent Weak Layer (PWL) avalanches have occurred so far this season in Utah.

It’s also important to note that with persistent weak layers, avalanche behavior is unpredictable, remote triggering is likely, and tests and observations can be misleading or unreliable based upon spatial variability. Note work done below on Travel Advice for the Avalanche Problems by Wendy Wagner of the Chugach Avalanche Center in 2014.

Conclusion

Persistent weak layers are a serious threat because they can remain dangerous long after the storm. By understanding how they form and how to identify suspect terrain, backcountry travelers can manage the risk more effectively. Always stay informed by reading avalanche forecasts, paying attention to terrain features, and making cautious decisions about where and when to travel in avalanche terrain. Stay safe, and remember that even MODERATE avalanche danger requires respect for the conditions. For many conservative people, this means choosing low-angle slopes with no overhead hazard or choosing aspects that do not hold this unstable structure.

The reality is that to steer clear of this avalanche problem completely, you must avoid steep slopes that hold this type of poor snow structure. If you don’t know what slopes those are, you must avoid them all.

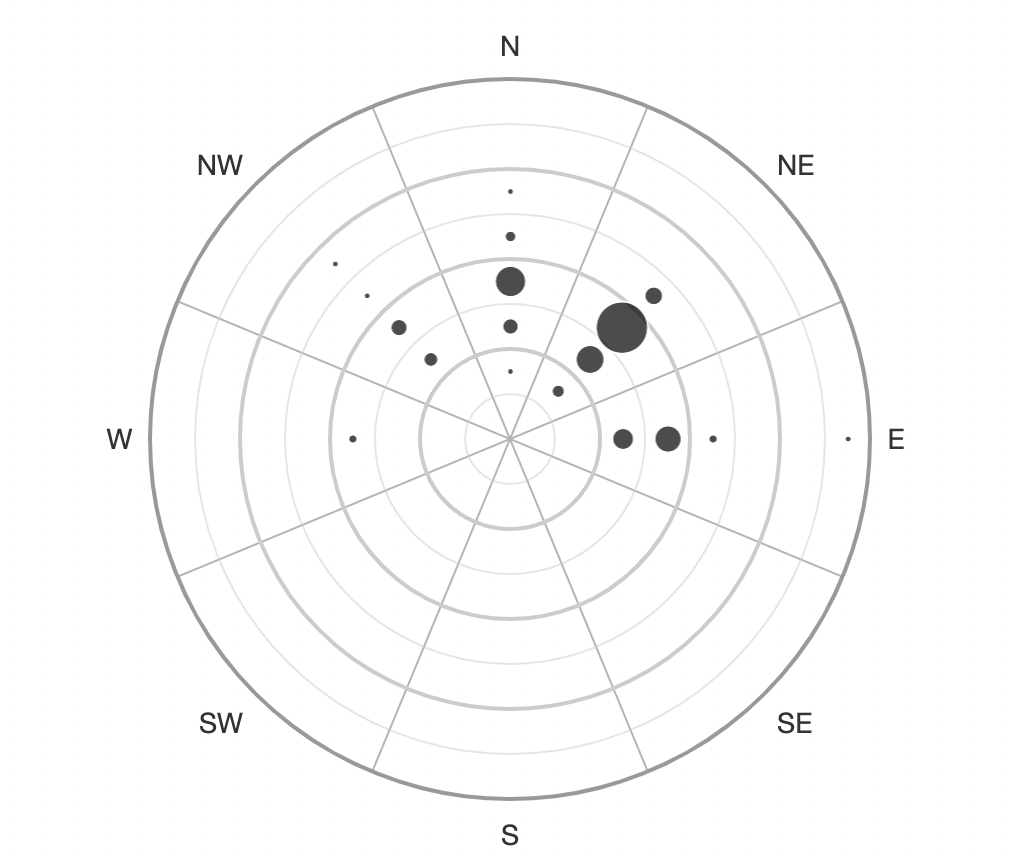

Above is a graph of PWL avalanches that have occurred so far this season in Utah (up to 1/26/25). The danger is very obvious when it is snowing and blowing, but as we move away from significant loading events, signs of instability start decreasing and it becomes much harder to identify suspect slopes. Outward warning signs like collapsing and cracking are less prevalent, and the slab may allow you to get out onto it before it releases.

A skier-triggered PWL avalanche occurred today (1/26/25) in Tibble Fork while I was writing this. See photo below.

OUTLOOK: Besides the buried persistent weak layer near the ground, the recent clear, cold nights are weakening the snow surface, adding another layer of complexity to this season’s avalanche conditions.

Please see Bruce Jamieson's video below. He does an excellent job of explaining the persistent weak layer or persistent slab problem.

This blog was written by Paige Pagnucco (Director, UAC), Jeremy Collett (UAC KBYG Coordinator and Educator), and Drew Hardesty (UAC Forecaster).