Observer Name

Staples and Meisenheimer

Observation Date

Sunday, January 19, 2020

Avalanche Date

Saturday, January 18, 2020

Region

Ogden » Farmington Canyon » Farmington Lakes

Location Name or Route

Above Farmington Lakes

Elevation

8,400'

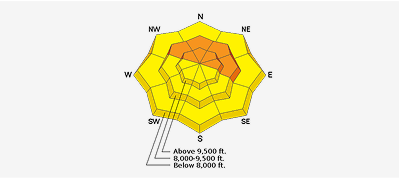

Aspect

East

Slope Angle

38°

Trigger

Snowmobiler

Trigger: additional info

Unintentionally Triggered

Avalanche Type

Soft Slab

Avalanche Problem

Persistent Weak Layer

Weak Layer

Facets

Depth

3'

Width

200'

Vertical

400'

Caught

1

Carried

1

Buried - Fully

1

Killed

1

Accident and Rescue Summary

Chase Adams (18 y/o) and his father were riding in Farmington Canyon on January 18. He was caught, fully buried, and killed on a slope just above the Farmington Lakes. Several other groups who own cabins in the area were riding nearby as well. At least one rider among these groups had ridden on the slope prior to the accident. The photo below was taken the morning of the avalanche.

Chase was sidehilling across the slope just above several mature evergreen trees. The avalanche happened just after he passed the trees and began to turn downhill. At some point during the avalanche, he was able to deploy his avalanche airbag.

He was carried in the avalanche and fully buried at the toe of the slope where the debris piled up deeply. His father was parked on the other side of the two small lakes and witnessed the avalanche. He called 911 at approximately 1:38 p.m. Chase was wearing an avalanche transceiver, but his father was not. Other people riding in the area including some cabin owners, saw the avalanche and came to help.

One person began searching with a transceiver and detected Chases' signal. As this person got close to the burial location, he became a little confused because the direction lights on his transceiver were flipping back and forth which can happen when you are directly over a buried person. In the confusion, he switched his focus from the direction lights to the numbers indicating distance to the victim. He moved to a location where he got the lowest number which was 4 meters. Then they began searching with a probe and got a probe strike after about 10 tries. They began digging. They also noted the depth of the probe strike was 180 cm (almost 6 ft). It is likely the probe struck Chase's backpack or the inflated air bag. At some point during the digging process, a shovel punctured the airbag and deflated it.

Note about the transceiver search: The searcher was using a modern avalanche transceiver that turns off the direction lights when the distance gets below 2 meters. Unfortunately, this was a deep burial which can be challenging. The searcher used the right method by switching to a bracketing or grid search method and ignoring the direction lights.

Davis County Search and Rescue (DCSAR) personnel were paged at 1:41 p.m. and the first two personnel from DCSAR arrived via helicopter at 2:17 p.m. (39 minutes after the 911 call) They commented that everyone seemed exhausted from digging up to that point.

Based on interviews with multiple people, it took approximately 50 minutes from the time of the avalanche until they reached Chase's airway and cleared it of snow. It took at least another 20 minutes to fully extricate him. He was found facing slightly downhill. He was transported to the University of Utah Hospital via an AirMed helicopter. The following day his snowmobile was found buried slightly below his feet.

Photo of the slope the morning of the avalanche.

Overview of the avalanche. The burial location is immediately uphill of the people.

Photo of his tracks traversing above a few trees into the avalanche starting zone.

Photo of burial location. The probe is held with 180 cm at the surface. The total depth of the excavation was 11 feet.

Terrain Summary

This slope faces almost due east, and the elevation of the avalanche crown face was 8400 feet.

Classification for this avalanche is SS-AM-R2-D2-O (SS - soft slab, AM - artificially triggered by snowmobile, R2 - small avalanche relative to the size of the path, D2 - destructive enough to bury, injure or kill a person, O - it broke within old layers of snow)

Slope angles range from 38 degrees near the crown face to 36 degrees in the middle. Below and through a rock band, the slope steepens to 40 degrees and then ends abruptly in on the upper Farmington Lake. This abrupt transition is a terrain trap that causes avalanche debris to pile up very deeply compared to slopes with a gradual transition to lower angle slopes. It acts just like a gully or creek where avalanche debris has nowhere to go. Avalanche airbags do not work well in terrain traps.

Burial location: 40.97560 -111.82022

Alpha angle of the toe of avalanche debris: 29 degrees

Weather Conditions and History

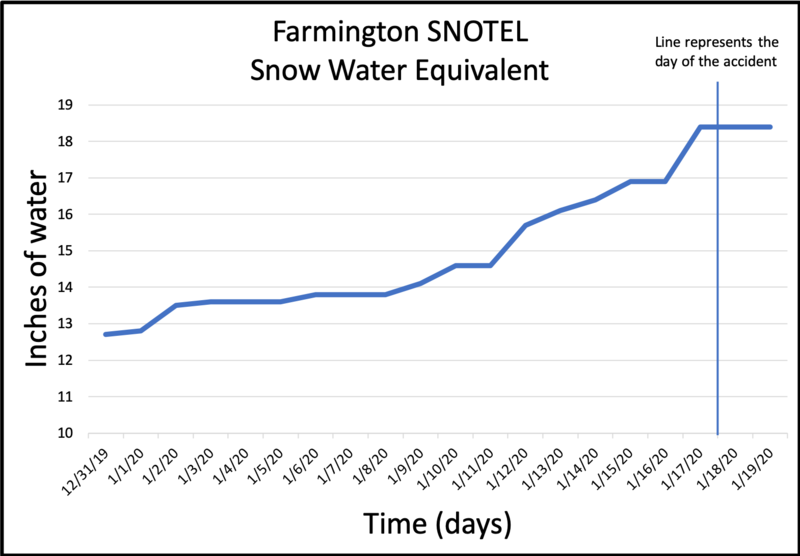

Precipitation

Precipitation data is taken from the Farmington SNOTEL site which is 0.64 miles to the south of the accident site. The day before this accident the area received about 9 inches of snow (containing 0.6 inches of snow water equivalent). Snowfall containing 3 inches of water had fallen between Jan 9th and the afternoon of Jan 14th.

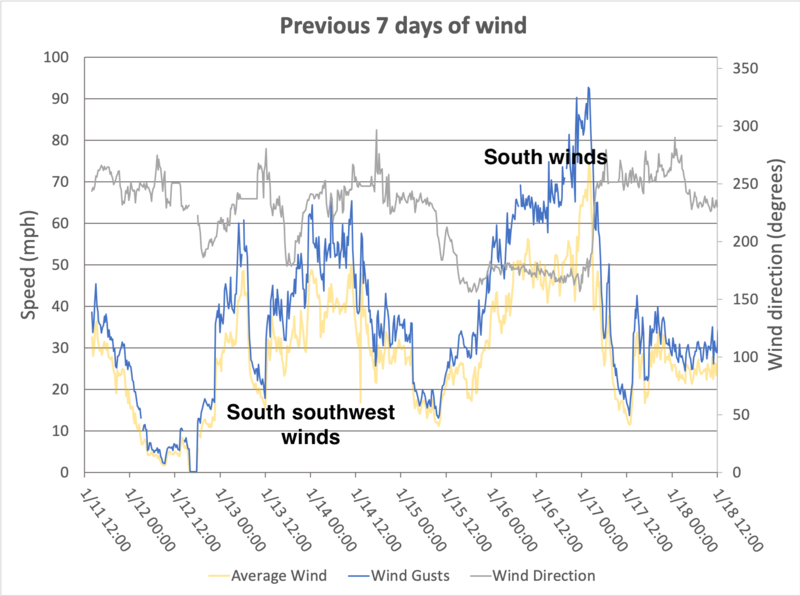

Winds

There are no upper elevation weather stations recording wind near the accident site. The best wind data comes Ogden Peak at an elevation of 9,570 feet, 16 miles to the north. While this wind site is at a higher elevation, it records winds that are mostly unaffected by terrain. The ridgeline above this accident is only at 8500 feet but has no terrain in front of it. Bountiful peak which is along the same ridgeline about 0.8 miles to the south may have blocked some south winds.

Strong winds from the south-southwest blew 30-50 mph and gusted 40-60 mph from Jan 13th to Jan 14th. Even stronger winds blew 45-55 mph and gusted 65-90 mph from the south on Jan 16th to 17th. These winds likely transported some snow over the ridge and onto the slope that avalanched. However, with such strong winds, the wind loading was not obvious as they would have transported snow much further off the ridge and been deposited further down the slope. Because we could not investigate the crown face, these comments about wind loading are speculative.

Short video showing windward terrain above and west of the avalanche.

Snow Profile Comments

We were unable to record a crown profile because there was too much hangfire (snow remaining above the crown face) to access the crown safely. Instead, we dug two snowpits on a 30 degree slope about 100 ft north of the avalanche. Pit 1 seemed like it had been affected by winds and we dug another Pit which is graphed below. Locations of these two pits are marked in a photo below.

Comments

The snow profile was recorded in the location marked by a red circle in the photo below. A short discussion is in the video below. We found the same weak layer on Jan 9th five miles to the south above the town of Bountiful. It can be viewed HERE and the full observation HERE. It was an interesting weak layer because we had not seen avalanches happening on this weak layer or any other signs of instability other than the results from Extended Column Tests. We revisited the area above Bountiful on Jan 14 during a storm (observation HERE) and were unable to see if any avalanches had occurred on this weak layer. Despite continual loading on this layer, ECT scores had climbed into the 20s and not all columns were propagating which was a positive sign.

Comments

Avalanche Danger

This location exists on the border between the Salt Lake and Ogden forecast zones, but it is generally considered part of the Ogden zone. The avalanche forecast for Saturday, Jan 18 rated the danger for that terrain as MODERATE. The avalanche problem was Wind Drifted Snow.

Signs of Instability

The day after the accident, Mark Staples and Trent Meisenheimer visited the area. The only avalanche spotted was a small slab of wind drifted snow. Riders had put a few tracks on other slopes without incident.

Comments

We aim to learn from accidents like this and in no way intend to point fingers at victims. All of us at the Utah Avalanche Center have had our own close calls and know how easy it is to make mistakes. Our intention is for this report to offer a learning opportunity. For that reason we have the following comments.

(1) This slope ended in a terrain trap that is not obvious like a creek or gully. Because there was such an abrupt transition from a steep slope to a perfectly flat slope (the frozen lake), the debris piled up very deeply.

(2) Deep burials (greater than 6 feet deep) are very difficult to survive. Even shallow burials require exhausting digging to reach a buried person because avalanche debris sets up like concrete. It is very dense and heavy, and it makes the digging very time consuming and grueling work.

(3) Avalanche airbags are great lifesaving devices that can decrease mortality from 22% to 11%. However, they are not a sure thing. On January 1st in Montana, a snowmobiler was buried 7.5 feet deep with a deployed airbag. Read more about the statistics HERE or the detailed scientific study HERE. In the case of this accident, even though Chase deployed his airbag, he was fully buried because the debris ran into a terrain trap.

Of note: Since last winter at this time, there have been 6 avalanche fatalities in Utah in which the victim or someone in their party was missing critical safety gear which includes an avalanche transceiver, probe, shovel, and partner(s) in a safe location ready to respond.

Our deepest condolences go out to the friends, family, rescuers, and everyone affected by this tragic accident.

Coordinates