Many large and dangerous human-triggered avalanches have occurred over the

past several days, failing on a layer of faceted snow (a

persistent weak layer) that formed during the January/February drought. Avalanches failing on this weak layer are 2-4' deep and well over 100' wide and can easily catch, carry, bury, and kill a human.

Now is a difficult time because triggering one of these avalanches is getting a little harder to do each day, and there may not be as many obvious signs of instability while traveling. The challenge is, avalanches issues don't just turn on and then turn off after a few days. Instead, the odds of triggering a slide decreases just a little each day, and then increases again when it snows or the wind loads a slope. Unfortunately, we don't know the exact odds of triggering one of these deadly slides; we just know it remains possible today.

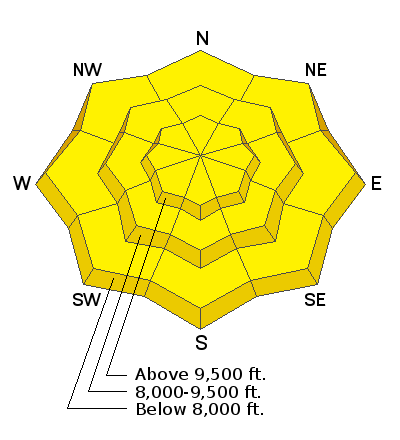

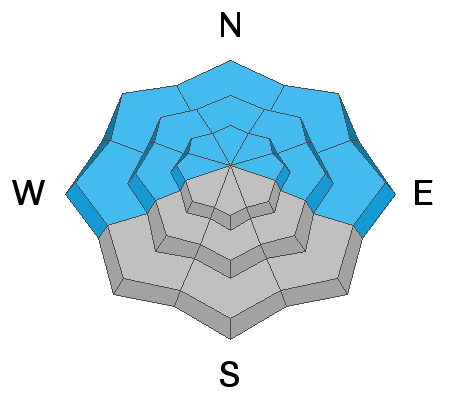

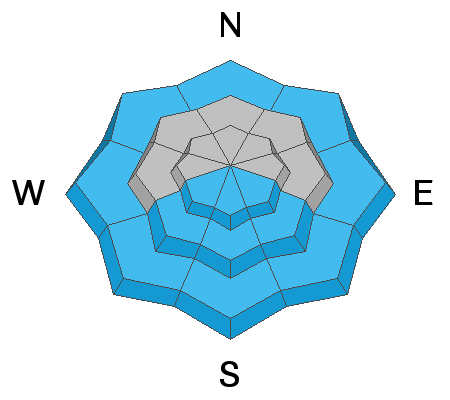

There will come a time we can begin pushing it out onto north-facing slopes with confidence, but that time isn't quite here yet. Just because the likelihood has decreased doesn't mean the problem no longer exists. Personally, I am going to continue to avoid being on or below slopes steeper than 30 degrees on the north side of the compass for the time being. I have very little confidence in the snowpack right now. If you do choose to ride slopes where this layer exists, stack the odds in your favor by choosing slopes with a clean runout zone free of trees and rocks that would cause trauma if you do trigger an avalanche.

A few things to remember when dealing with persistent weak layers.

- Persistent weak layers can be triggered remotely, from a distance, or from below. Look at the avalanche in Millcreek.

- Avalanches can happen on short steep slopes in "what we think is benign terrain." Remember, avalanche terrain is anything over 30° in steepness. Read Lucky Days & Silver Fork.

- This avalanche problem can produce very large avalanches that run long distances. Look at the slide in Mineral Fork.

- Signs of instability may not always be present: you may or may not see or experience shooting cracks or audible collapsing.

- Tracks on the slope offer zero signs of stability. Avalanches can take out multiple existing tracks.

A valuable note from Trent yesterday: "By my count, we've had eight very close calls, and in fact, all of these close calls are by people that are either avalanche professionals or very experienced backcountry riders. This tells me that if the avalanche professionals are getting it wrong, we all need to take two steps back, and re-evaluate our decisions."