Observer Name

UAC Staff

Observation Date

Sunday, February 9, 2025

Avalanche Date

Saturday, February 8, 2025

Region

Salt Lake » Big Cottonwood Canyon » Silver Fork » East Bowl

Location Name or Route

East Bowl

Elevation

10,300'

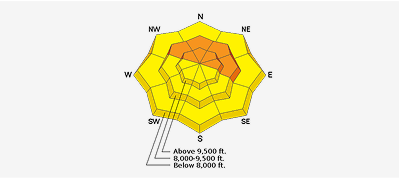

Aspect

West

Slope Angle

38°

Trigger

Skier

Trigger: additional info

Unintentionally Triggered

Avalanche Type

Soft Slab

Avalanche Problem

Persistent Weak Layer

Weak Layer

Facets

Depth

2'

Width

125'

Vertical

800'

Caught

2

Carried

2

Buried - Partly

1

Injured

1

Killed

1

Accident and Rescue Summary

On the morning of Saturday, February 8th, 2025, a long time ski guide Higinio “Quino” Gonzalez met his client in upper Little Cottonwood Canyon to discuss ski plans for the day. It was a beautiful morning with abundant powder on all aspects. The two settled upon skiing in Grizzly Gulch and Michigan City, generally benign and well-known backcountry ski terrain in the Wasatch. They skied two south facing runs into Michigan City and then ascended back up to the Cottonwood ridgeline above Silver Fork. At this point, Quino tells his client that they’ll ascend to near the top of Honeycomb (or East) Peak to take a look into the East Bowl. The East Bowl is steep west facing terrain and offers excellent skiing. It is also a well known avalanche path. According to the client, there was little to no discussion regarding the merits of the slope, only that it was clear that it looked to be an excellent powder run.

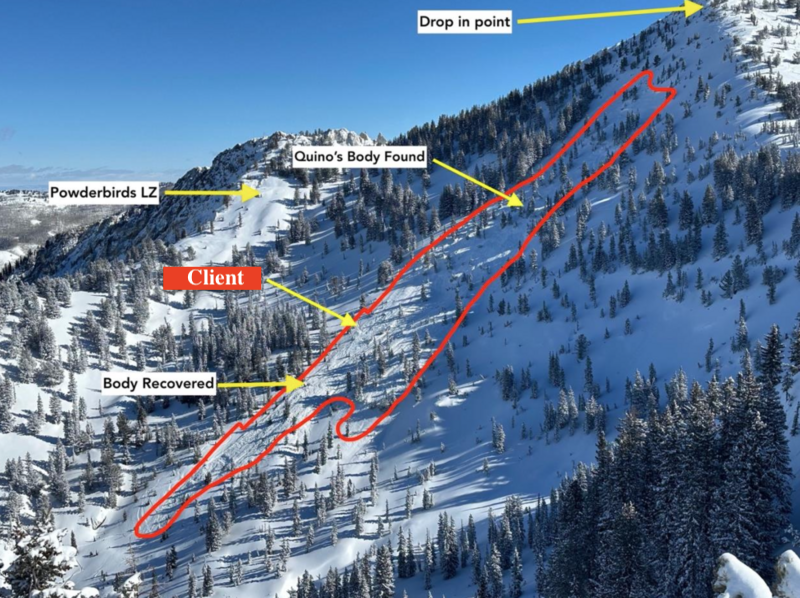

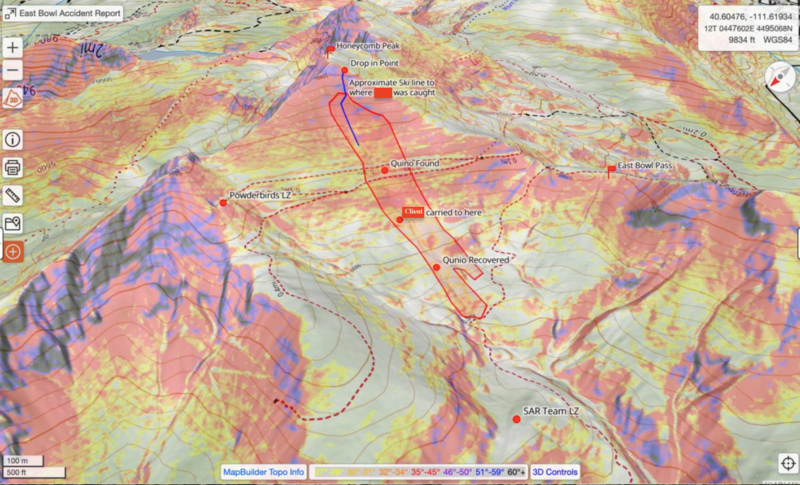

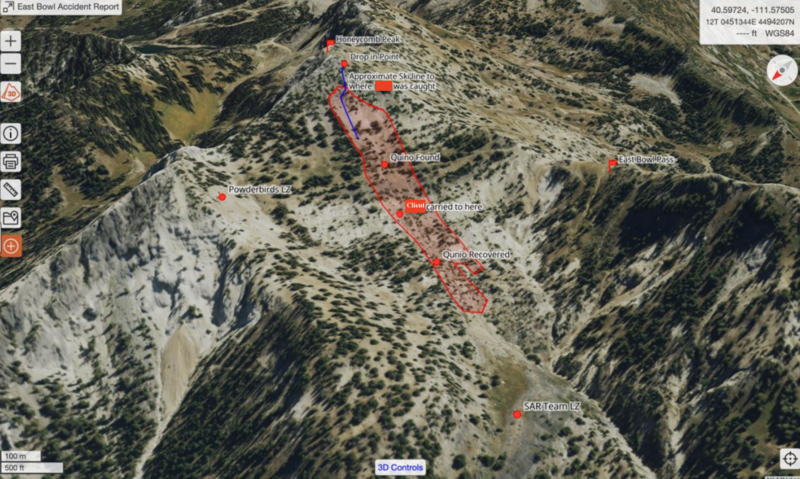

Once they gained an elevation of roughly 10,400’, they ripped skins and peered into the bowl. Quino told his client that he (Quino) will traverse onto the slope, do a ski cut, and then ski the fall line. He told the client to “wait 15 seconds and then follow my line.” The ski cut produced some very minor sluffing. The client waited the 15 seconds, traversed in, made four turns and the slope shattered all around him. (general depiction of ski tracks below). The client swam, lost his skis, slammed a tree, and continued with the avalanche to the bottom of the slope. He was partially buried with a fractured tibia and fibula and some face lacerations, but hasn’t yet realized the extent of his injuries. His only thought was that he is glad to be alive. And then he began yelling for Quino. Unbeknownst to the client, Quino had also been caught and carried in the avalanche and was carried into a tree and suffered immediate traumatic injuries incompatible with life. He did not survive.

On this day, It was around noon when Jeff Hardin and his 15 year old son got to the top of the West Bowl of Silver Fork. They saw a fresh avalanche in the East Bowl and descended to the West Bowl flats to traverse over to the East Bowl. They soon heard screams for help. Enroute to the accident site, they came across another skier Maria Saldutti whose partner Will Robbins was already headed for the debris pile. It should be noted that Jeff is an ER physician; Will is a wildland firefighter and also an EMT. Will initially arrived at the injured client, performed a rapid assessment and then continued up to find Quino. Jeff soon arrived at the client’s position, similarly ruled out any immediate life threatening injuries, and ascended the debris to find Will and Quino. Quino was found pulseless and with significant massive chest trauma. Still, the two performed CPR for an estimated 30 minutes. At this time, a Powderbird helicopter landed with Powderbird guides and then members of Alta and Snowbird ski patrol, who immediately provided care and packaging to the client. A Utah Department of Public Safety helicopter hoisted the client to the Incident Command Post where he was soon transferred to Intermountain Health Care to attend to his broken leg. Members of Salt Lake County Search and Rescue packaged Quino to be transported to the ICP; however, deteriorating weather conditions ceased the air operations and Quino was recovered the following day.

(Rescue photo S.Chovan, WBR pic)

Terrain Summary

(Photo of avalanche from below the toe: Ryan Clerico, SLCSAR)

This avalanche occurred on a west-facing slope named East Bowl in upper Silver Fork, in Big Cottonwood Canyon, southeast of Salt Lake City, UT. The crown face was between 10,200' and 10,300' and the toe of the debris was approximately 9,500 feet in elevation. Slope angles in the starting zone ranged from 35 degrees to 40 degrees in steepness. The avalanche ran approximately 800 feet in elevation.

Weather Conditions and History

In Utah, a fairly dry early season led to many mountain locations registering well below normal for snowpack.. It wasn't until the Christmas Holidays that Utah experienced its first significant storms of the winter. These storms led to many natural and human triggered avalanches that failed on early season facets and depth-hoar near the bottom of the snowpack. On December 29th, an avalanche class - from the safety of the ridgeline - remotely triggered the East Bowl from East Bowl Pass all the way to near the Flanagan’s shoulder with propagation over 1000’ wide through significant stands of trees. The crown was estimated to be 2-3’ deep, propagating from north to west to slightly southwest facing. This was one of hundreds of avalanches that occurred over the course of the holidays. It was a dangerous time with an avalanche fatality occurring on December 28th and another on December 31st. Unfortunately, many of these avalanches did not remove the entirety of the facets and depth hoar; leading to many slopes “repeating” as avalanches upon being reloaded by subsequent snowfall and/or wind.

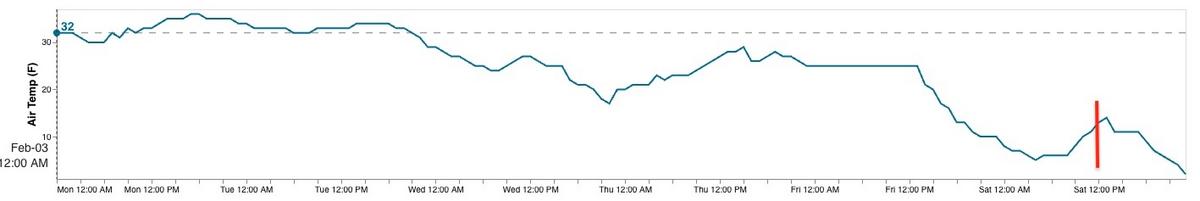

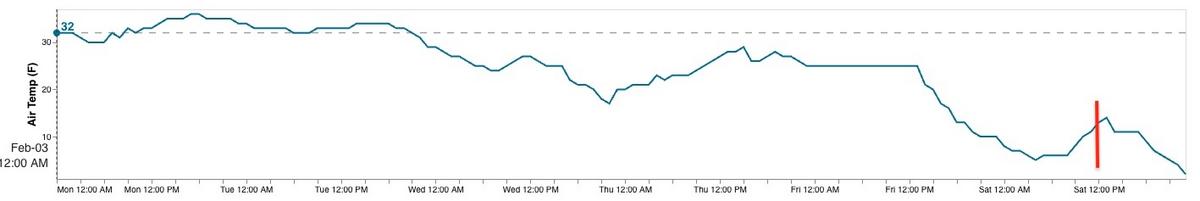

A late January dry spell led to recrystallization and faceting of the snow surface and this layer was buried on the 1st of February. Subsequent storms produced avalanches on this layering before a significant warm-up the first week of February. A quick-moving winter storm moved into the region on the morning of February 7. By the morning of February 8, the storm had dropped 12-20 inches of snow and 1.40-2.85 inches of water in the Upper Cottonwood Canyons. Moderate to strong winds accompanied the storm, blowing 10-20 mph from the south and gusting to the mid-40s mph at nearby weather stations. The start of the storm was primarily graupel and overnight on the evening of the 7th the new snow was lower density as temperatures fell.

On the day after the accident, Utah Avalanche Center forecasters Dave Kelly and Drew Hardesty went toward the accident site to better understand the nature of the event. There was universal agreement, however, that conditions remained too dangerous to access the fracture line of the avalanche and therefore avalanche information is only conjecture based upon slope and snowpack history. Based upon zoomed-in photos from both the rescuers and the drone, it is estimated that the soft slab avalanche was roughly 2’ deep. This potentially matches the layering of the faceted grains buried on February 1st and it could also match a weakness of graupel from the Friday February 7th storm. It is also conjectured that this slope had avalanched previously on December 29th, leaving a layer of weak faceted snow on the bed surface. All three weak layers had been active prior to the accident.

(photo of crown; Hardin)

Based upon the nature of the snowpack with its attendant persistent weak layers, it is impossible to know exactly who triggered the avalanche.

On the day of the accident, the Utah Avalanche Center had rated the avalanche danger as CONSIDERABLE (link to forecast). The bottom line read as follows “The avalanche danger is CONSIDERABLE on all mid and upper-elevation steep slopes for slab avalanches. Here, avalanches can fail within the new snow or at the old/new snow interface. On northerly facing terrain, these avalanches could step down into buried weak layers of faceted snow, making them more dangerous. Human-triggered avalanches 1 to 3 feet deep are likely today.”

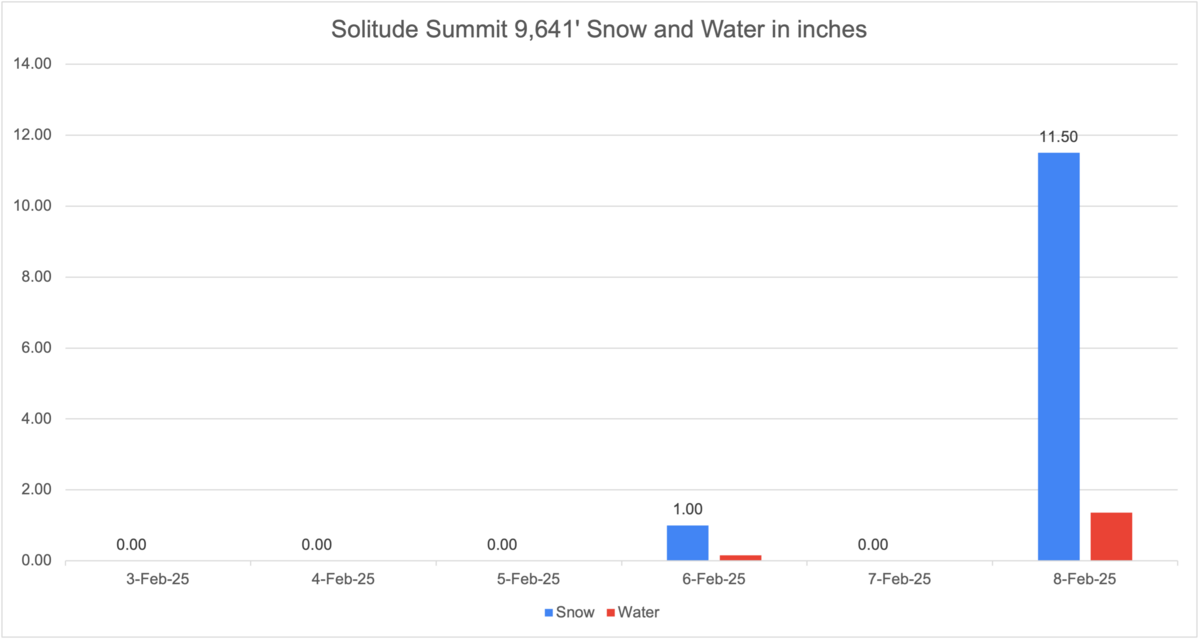

Solitude Summit (9,641') snow and water February 3-8, 2025 (located .6 miles southeast of the accident site)

Honeycomb Peak (10,448') air temperature (above), wind direction and speed (below) for time period February 3-8, 2025 (located 400' southeast of the accident site)

Snow Profile Comments

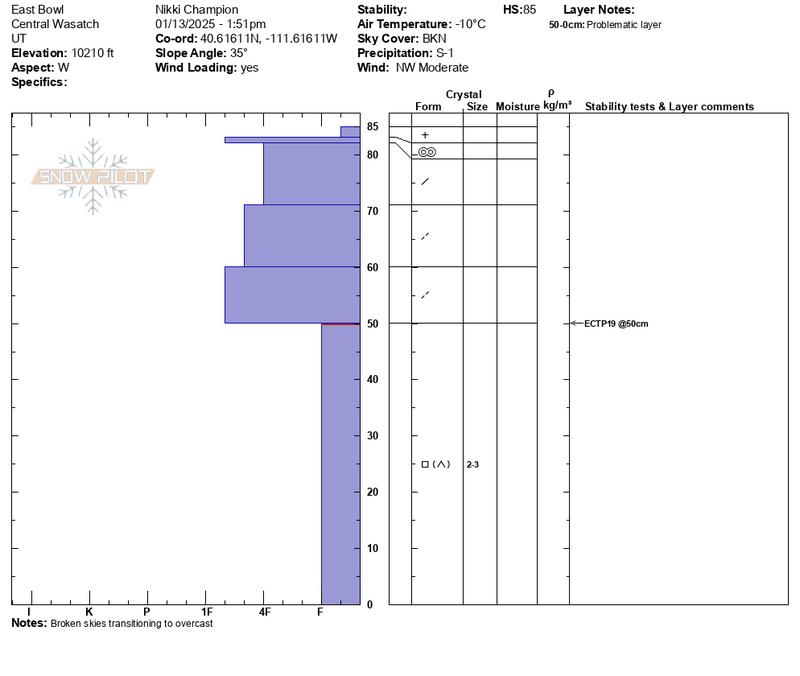

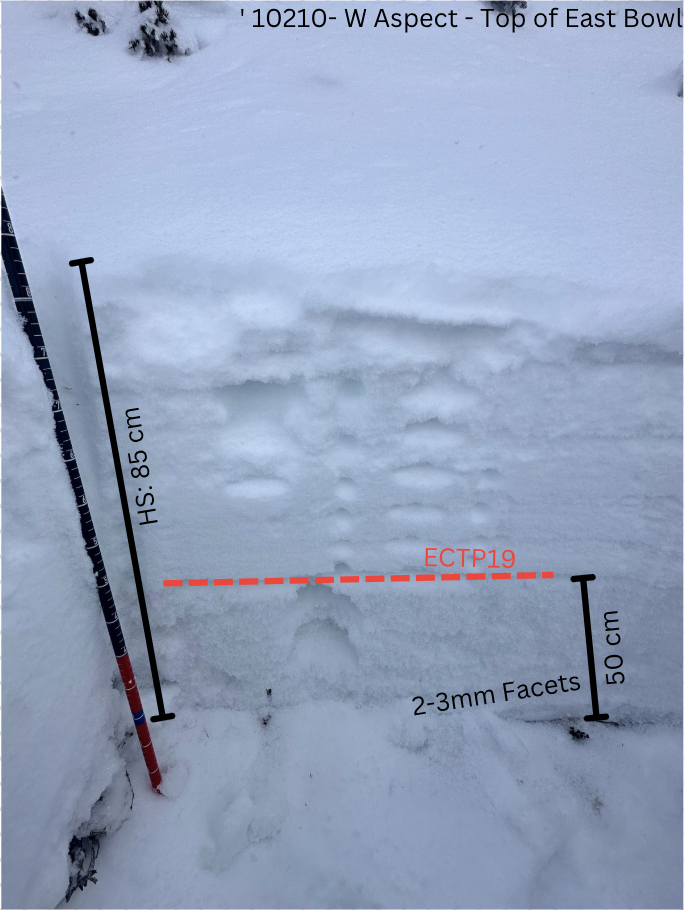

Throughout the season, multiple field days were conducted in west-facing terrain within the East Bowl zone. On January 13, UAC staff investigated a west-facing slope on the skier’s right shoulder below the top of East Bowl at 10,210’. This slope, a known repeater with no obvious ski tracks, served as a key indicator for some of the most suspect terrain. Near the ground, we found approximately 40 cm of well-developed, cupped facets. Stability testing produced an ECTP19 failure on these basal facets.

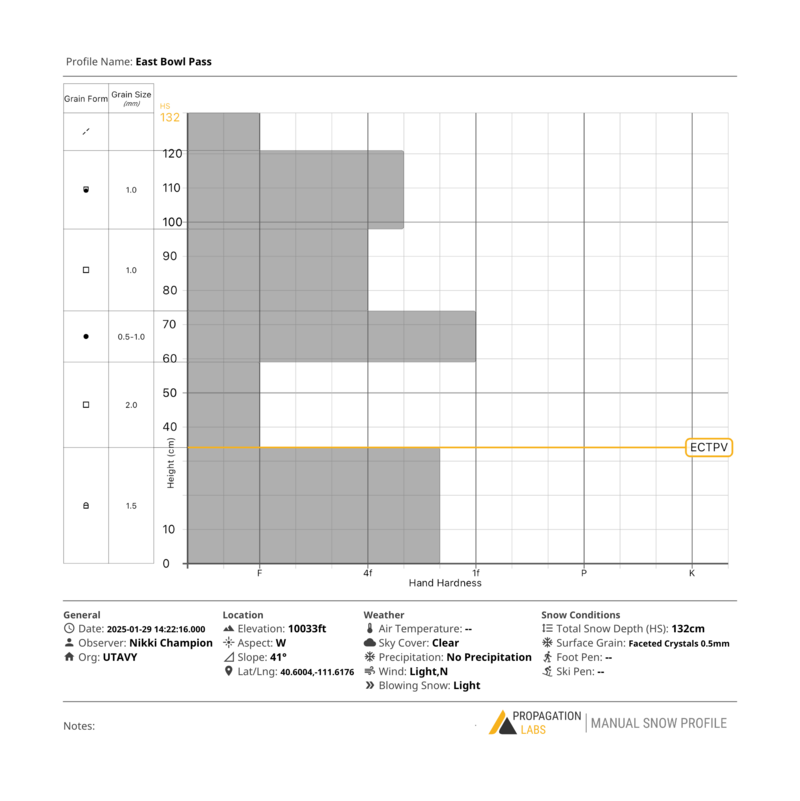

On January 29, UAC staff returned to the skier’s left shoulder below East Bowl and conducted another snowpit assessment on a west aspect at 10,033’ in a shallow, safely accessed zone. The height of snow at this location measured 130 cm, with extremely weak early-season facets found just 60 cm beneath the surface. Stability testing resulted in ECTP-V, indicating failure upon isolation within the basal facets.

While this deep instability did not appear to be widespread, it remained a factor in isolated terrain. Following the next storm, the primary concern was expected to be the new snow/old snow interface, which continued to facet. However, in shallower zones and previously avalanched terrain, there remained a chance that the deeper PWL could reactivate.

Pit Profile from East Bowl - W Aspect - 10210' 1/13/25

Pit photo from East Bowl - W Aspect - 10210' 1/13/25

Pit Profile from East Bowl - W Aspect - 10033' 1/29/25

Pit wall photo from East Bowl - W Aspect - 10033' 1/29/25

Comments

This report was compiled with support from many individuals and agencies, including Salt Lake County SAR, Powderbird, Wasatch Backcountry Rescue (Alta and Snowbird Patrols), as well as many good Samaritans from the backcountry, all of whom represent the best of our mountain community.

Video

Coordinates