Toby Weed

Forecaster

An impactful way to learn about avalanches is through stories, especially unsolved mysteries. Most avalanche accidents are tragic, but retelling stories memorializes those killed and can teach us, who intend to venture into avalanche terrain, valuable lessons. In May 1990, Bruce Tremper, then the Director of the Utah Avalanche Forecast Center, wrote the report on the Mark Miller Accident. The report lived in the 1989/90 UAC Annual Report until I pulled it out on the 35th anniversary of Miller's disappearance. I reworked Bruce's narrative a tiny bit and made a blog. Whether or not an avalanche killed Mark Miller, he probably would have survived had he just gone into the backcountry with a partner or companions, and had he survived, he would have been my age.

NOTE*** I created a PowerPoint with the report, but the pictures are not from the Mark Miller accident, but rather from more recent avalanches in the same area.

November 25, 1989, Mark Miller Avalanche Fatality, Tony Grove South

In mid-May 1990, the body of 24-year-old Mark Miller, an expert skier from River Heights in Cache Valley who had been missing since November 25, 1989, was found by two backcountry skiers about a third of a mile south of Tony Grove Lake. Although inconclusive, the evidence indicates that an avalanche killed him. This was the first avalanche fatality in Utah in nearly three years.

An accomplished skier, Mark Miller frequented the Logan area backcountry and was known to ski extreme terrain like the cliffs on the backside of Beaver Mountain. The previous year, he’d skied in the Tony Grove area at least a dozen times. Mark was a very experienced and fearless skier, but he had never taken an avalanche class, did not carry avalanche rescue gear, and was alone when he disappeared.

With about a foot of new snow and continuing snowfall, November 25 was probably the season’s first opportunity for good powder conditions. Friends last saw Miller hiking alone with alpine skiing equipment. He walked on foot, following the tracks of some snowboarders leading up the ridge from Tony Grove Lake, where he parked his car. The last person to see Mark, a friend and associate, said he mentioned heading toward the Mount Naomi area to go skiing.

A foot of snow had fallen the day before. Much of the new snow fell on bare ground, but some fell on a thin layer of recrystallized snow still remaining on the more northerly facing slopes—snow left over from the first significant snow of the season in late October, nearly a month before. There was a break in the weather, with an incoming cold front promising prefrontal winds and snowfall to commence in the late afternoon.

Miller did not return that evening. Two friends drove up to Tony Grove Lake that night around midnight, found his car there, and searched for him with headlamps, following his tracks up a ridge south of Tony Grove Lake. But a large winter storm was arriving in the Logan area mountains—one of the largest of the season. They lost his tracks as they ascended the ridge due to new snow and increasing winds.

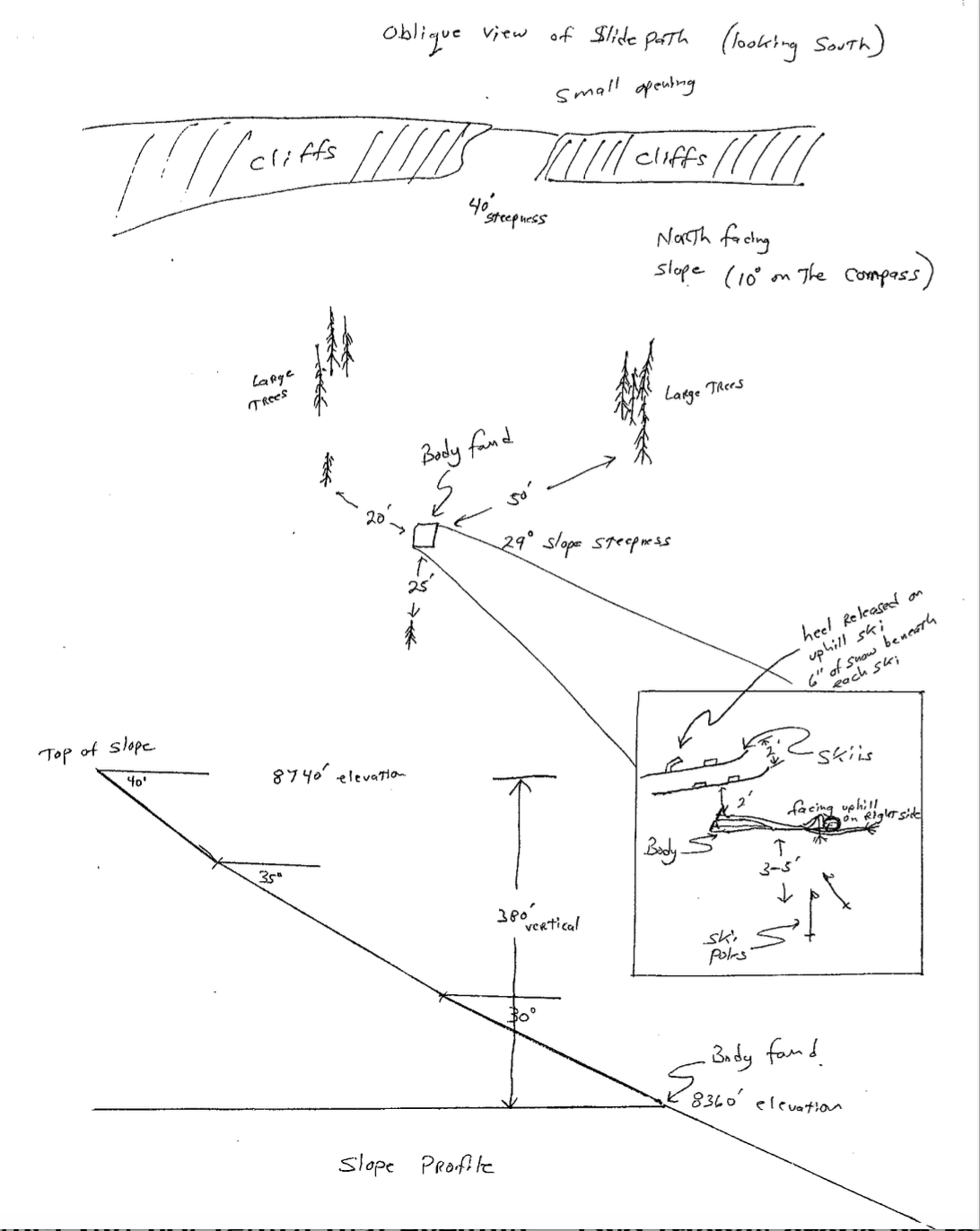

The following morning, a small hasty party on snowshoes searched through the blizzard with hazardous avalanche conditions, but they still found nothing. Two days after the accident, larger search parties searched the area and continued for over a week, with nearly 100 searchers at one point. One searcher with trained rescue dogs said that the dogs seemed to indicate near the slope where he was eventually found, but the owners wisely called them back as it was a hazardous avalanche path loading up rapidly during the storm. Another rescuer, Kevin Kobe, recalls seeing the remains of an avalanche buried by new snow on the same slope where Miller’s body was later found. The search was finally called off a week later, and smaller parties continued for another two weeks.

Then, in the spring, on May 22, 1990, two Logan area skiers were out with their pet dogs when the dogs began sniffing around the area. The skiers, suspecting that the dogs had found the missing Mark Miller, began digging and found his ski poles, then just uphill of that, the body, buried under five-and-a-half feet of snow. They went to notify the sheriff.

The Sheriff’s team found the body lying on its right side, facing uphill, right arm outstretched pointing uphill, the elbow cocked straight up in the air almost behind his head, and legs out straight. He still wore a hat and sunglasses. They did not find his skis, but Tremper and Kobe went in the following day and found them less than two feet away from his boots, both skis parallel across the hill, and the heel ejected from the uphill ski.

Because all his equipment remained so close to him and he still wore a hat and sunglasses, it first seemed to Tremper unlikely that it was an avalanche accident. Typically, an avalanche spreads equipment out over the slope and quickly tears off hats, glasses, and gloves. However, the medical examiner found no broken bones, no bumps on the head, etc, which might indicate that he fell and was injured while skiing the rocky, shallow snowpack. They concluded that he “died of suffocation from being submerged in the snow.”

In his report, Bruce Tremper wrote, “So perhaps the best conclusion is that he was pushed over in place by a fairly small avalanche and died of asphyxiation. He obviously did not ride the slide very far as it would have spread his equipment out more.” Bruce believes that he must have been near where he was found when he triggered a small slide that came down from above, knocked him down, and buried him. After that, the storm laid down a few feet of new snow, which kept rescuers from finding him until spring. Tremper’s report concludes that “this is most likely an avalanche fatality but not unquestionably so.”

Tremper asks how this accident could have been avoided and answers;

-First, if he had more avalanche knowledge (he had taken no classes).

-Second, he would most likely be alive if he was skiing with a partner and both had beacons and shovels and skied it one at a time.

Bruce wrote, “It must have seemed like an innocent slope at the time. Yes, it was steep, but it had very little snow on it. Many people get sucked in by the ‘there’s not enough snow to slide’ trap. It was early season with the first skiable snow of the season and passions run high when ski fever sets in.”

The tragedy of this accident resembles most others in that it was easily avoidable.

I was part of the group of snowboarders that Mark was hanging out with early that season. We kicked and maintained the "stairway" from the Tony Grove campground that Mark followed to the ridge that day. It was one of the hills we used early in the season, before Beaver Mountain would have enough snow to open. It was accessible from Tony Grove Lake, until the winter snows shut the access road down. We called the place #11s, because we would always start our post-hole stairway from the post marking campsite #11. I did not go up on the day he disappeared, but the word was that it was already snowing when the two boarders headed down passed Mark who was climbing up. I believe the narrator gets the story correct, particularly regarding him being alone and all of our groups lack of avalanche training and experience. Our guys supposedly tried to tell the searchers where they should look for him, because where he was found was a common "last run of the day," when it was time to head back down to the cars. They said the searches wouldn't listen, because they were perceived as just a bunch of hippy snowboarders. The rumors were rampant that season, including one completely unfounded suggestion that he was a drug dealer who faked his death and was alive incognito down in Las Vegas. We challenged all the scuttlebutt, because we knew he was still up there. I believe it was Scott Datwyler, the owner and manager of "The Trailhead" outdoor shop in Logan who went looking for him in spring and found the body.

Some good did come of it. It snapped the rest of us out of our youthful sense of invincibility. We began checking the regional avalanche forecasts before going into the mountains. From then on everyone in our group carried an avalanche beacon, probe, shovel, and some experimented with other avalanche technologies. We trained in proper search and rescue procedures. Many of us took courses in Avalanche and Snow Science, and when traveling in the back-country, we dug snow pack sheer test pits, did snow crystal analysis, and consider what loads might be piled up above us. We learned how to move safely in groups, and to ride one a a time safely in dicey terrain. It became part of our lifestyle, and nobody died after that.

Rest in Peace, Mark.

Donald Piburn (not verified)

Thu, 5/8/2025

- reply