When the first significant storm paints the peaks white and we're getting stoked for winter, it's time to start thinking about how that first layer will affect snowpack stability during the upcoming season. In a perfect world, it will keep right on dumping and we'll be ripping deep, stable snow by Christmas. But, as is often the case, we could see a return of high pressure, and then we'll be left with snowed in bike trails, cold crags, and a rotting foundation for our snowpack.

When shallow snow sits on the ground under cold clear skies it begins to transform, or metamorphose into a pile of loose, dry, sugary crystals called depth hoar. Lacking cohesion, and in turn strength, depth hoar is the bane of a snowpack. As a weak base layer, these large grained, faceted crystals can become the failure point for large, dangerous, and unpredictable full depth avalanches. And depending on your geographic location, and the type of winter you are having, depth hoar can plague your snowpack from as little as a few weeks, to a few months, or even for an entire season.

Depth hoar forms through a process known as temperature gradient metamorphism which isn't quite as complicated as it sounds. In winter, the ground, insulated by a layer of snow, has a temperature right around 32 degrees which is generally quite a bit warmer than the air temperature. When the ground loses heat into the atmosphere it causes vapor to transfer up through the snowpack. As the vapor moves upward, it recrystallizes into plates or facets on the bottom of overlying crystals. This faceted snow is square, angular, and has poor bonding properties as opposed to rounded, sintered grains which make up a strong snowpack.

Temperature gradient refers to the difference in temperatureover some distance, which in this case is the depthof the snowpack. When the insulating layer of snow is shallow, the gradient is larger because there is a big temperature difference over a short distance. This causes more heat to be lost to the atmosphere resulting in more vapor transfer, and hence faster growing facets. This is where the old adage “a shallow snowpack is a weak snowpack” comes from. As the snowpack gets deeper, the process slows down and eventually reverses, and grains turn from faceted and weakto round and strong.

The prevalence of depth hoar is largely determined by region. Continental climate areas such as the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, are notorious for depth hoar and by February, the entire snowpack may consist of weak faceted snow. In the inter-mountain region of northern Utah, Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana, where snowfall is usually greater, depth hoar is typically, but not exclusively, an early season phenomenon. In the wet maritime snowpack of the Pacific Northwest, depth hoar is almost non-existent, but in the Sierra Mountains of California, a place known for it's heavy wet snow, or “Sierra Cement” depth hoar can still form early season, especially along the east side of the range where snow is often dry and shallow in comparison to the west side.

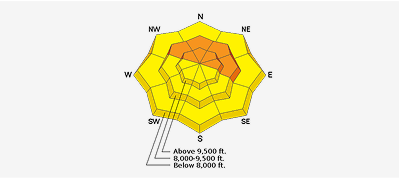

In mid latitudes, depth hoar forms primarily on shady, northerly aspects where the temperature remains the coldest, and the snow receives little to no solar radiation. In these cold dark places, faceted crystals develop and can remain for long periods of time. This is one reason why avalanche advisories often single out these areas as the most dangerous. In northerly latitudes and in colder climates, depth hoar can also develop on southerly aspects in shallow snowpacks.

My first experience with a serious depth hoar snowpack came from what is now my home range, the La Sal Mountains of Southeastern Utah. The La Sals have a shallow, weak snowpack and are much more akin to the mountains of Colorado than the Wasatch Range where I had grown up skiing, started touring, and eventually became a snow professional on the Alta Ski Patrol. I had gone down to the La Sals to tour with Dave Medara, who had recently left the Alta Patrol to take over forecasting duties after a devastating avalanche accident killed the previous forecaster and three others.

Medara tried to explain to me that this place was different from what I was used to, and as we turned off the snow packed road on to the skin trail, my ski pole went straight to the ground through three feet of loose, faceted snow. I had never seen anything like that before but I knew it wasn't good. We tiptoed around the rest of the day sticking to ridge crests and low angle wooded areas. Occasionally we would cross an open meadow and the entire snowpack would collapse under our weight, the ominous whoomphing sound leaving our hair standing on end.

But the dangers of depth hoar don't always present themselves so readily. Often times the loose, faceted grains are lurking far beneath subsequent layers of snow and you have to dig down to find them. In this case you have to do some serious calculation of risk. Picture a house of cards. Each passing storm adds an additional load to a fragile base. Small, incremental doses are the hardest to gage. Whereas big dumps can result in a wide spread avalanche cycle, small storms that don't cause the house to crumble can leave you on pins and needles wondering if your additional weight will be enough to tip the scales.

As the season progresses and the snowpack grows deeper, and in many cases stronger, spatial variability comes into play. Depth hoar persists in areas where the snowpack remains shallow. Shady mid elevation slopes, areas of frequent wind scour, rocky outcroppings, and the bottom of basins where cold air pools remain suspect.

In my travels over the years in a depth hoar plagued mountain range, I've had to learn to scale back my expectations significantly. Careful monitoring can give you clues to strengthening snow but you have to dig, and you have to be patient. Over the long run, you can measure the temperature gradient – 1 degree centigrade over 10 centimeters of snow is the threshold – but that does little to tell you about the here and now.

The only sure way to manage a depth hoar snowpack is to avoid slopes where it exists. When conditions are sensitive, and signs of instability such as whoomphing and collapsing are present, avalanches releasing on depth hoar can be triggered remotely. Stay out from under steep slopes and be careful to avoid locally connected terrain. When conditions grow less sensitive, you'll still need to perform stability tests to assess the underlying weakness.

Avalanche professionals over time have relied on the old saying “never trust a depth hoar snowpack.” Prudent words to live by. Pay attention to that first snow on the ground and watch how it stacks up from there. And if it turns into a pile of sugary facets, keep your early season stoke in check and wait for things to get deep and strong before you hang it out there.