This is the problem... avalanches are breaking from a distance and low on the slope like the avalanche in the image above which occurred yesterday afternoon on a north facing slope in Weber Canyon. It was triggered on an adjacent low angle slope, broke deep and wide, running into a group of trees and stacking up a surprising amount of bone snapping debris.

Some recent thoughts from boots on the ground-

"I can’t remember a time that I’ve seen more red flags in one ride. We observed widespread cracking and collapsing. Avalanches were easily triggered on any test slope steeper than 30 degrees. Snowpro, avy educator extraordinaire,Wasatch SAR member, pro sledder, and all around great guy Tyler St. Jeor states it best in his comment from Saturday.

"We were fooled by old tracks and a lack of signs of instability" (which is the nature of avalanches that fracture on persistent weak layers of facets.) Family involved in Saturday's close call near Humpy Peak

I'm still thinking through the incident and lessons to share but 2 critical errors that stand out to me are: I thought that I could manage the terrain to avoid the avalanche problem. I thought that the most likely place to trigger the avalanche would be high up on the slope and close to the ridge in one of the primary start zones. Snowpro and avy educator with a solid snow sense and impressive acumen, my friend and colleague Bo Torrey reflects on yesterday's avalanche in Upper Weber Canyon

Here's the deal-

Remember the big dryspell during January/February? (You're thinking to yourself... hmmm, "I forget what time I drop the kids off for soccer practice today.") Well, that midwinter drought helped create a weak layer of faceted, sugary snow which is now buried under several layers worth of storm snow from last week. And while we might forget everyday occurrences, the snowpack has an amazing memory. In fact, now that this layer is buried, it's our new problem child, or persistent weak layer (PWL).

Chads weekend viddy above illustrates the problem. We've got an unusual, late season, set up... strong snow on top of weak snow. And the weak layer is easily failing under our additional weight and will produce deep, dangerous avalanches today. Like a layer of dominoes with stronger snow resting on top, once our skis or track tip the first domino, it sets off a chain reaction in which all the dominoes (PWL) collapse. It's sorta like pulling the rug out from underneath, and the entire roof crashes down on us! Here's where it gets tricky... we don't even need to be on a steep slope, just near or connected to it (at the top, bottom, or to the side). Tip one of the dominoes over and now we're staring down the barrel of a scary avalanche!

What makes this situation tricky?

- We don't normally deal with long lasting avalanche problems like this, lingering deep into the winter. Today's avalanches act more like early and mid season slides that break on sugary snow near the ground except in this case avalanches will break in the middle of the snowpack. Avalanches may also break in areas below treeline where we don't often expect to see as many slides.

- You can trigger deep, dangerous avalanches by simply being near a steep slope but not necessarily on it.

- This weak layer is found on many slopes but not all, especially in the wind zone, where distribution is spotty and that makes stability patterns tricky to get a handle on. So... you might find weak snow on one part of a slope but not the other. This means you may see people ride a slope and not trigger a slide, but the second or third person on that same slope may be the one to trigger and avalanche.

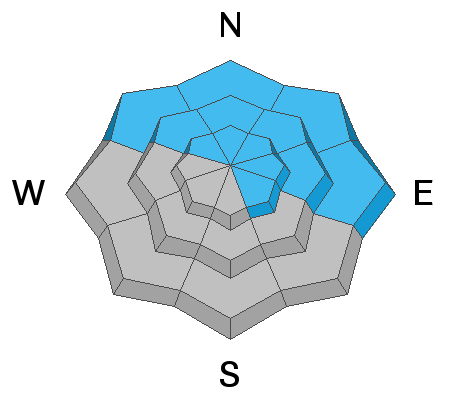

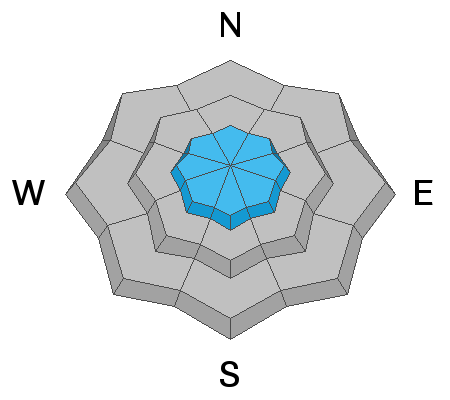

What's the exist strategy? There are two options. Ride southerly facing slopes that don't have this weak layer, but the problem is they have a much thinner snowpack. Terrain facing the north half of the compass offers a deeper snowpack and cold powder, but likely have this weak layer and are unstable. In those areas, simply ride slopes less than 30 degrees in steepness with no overhead hazard... and that means nothing steeper above you.