Drew Hardesty

Forecaster

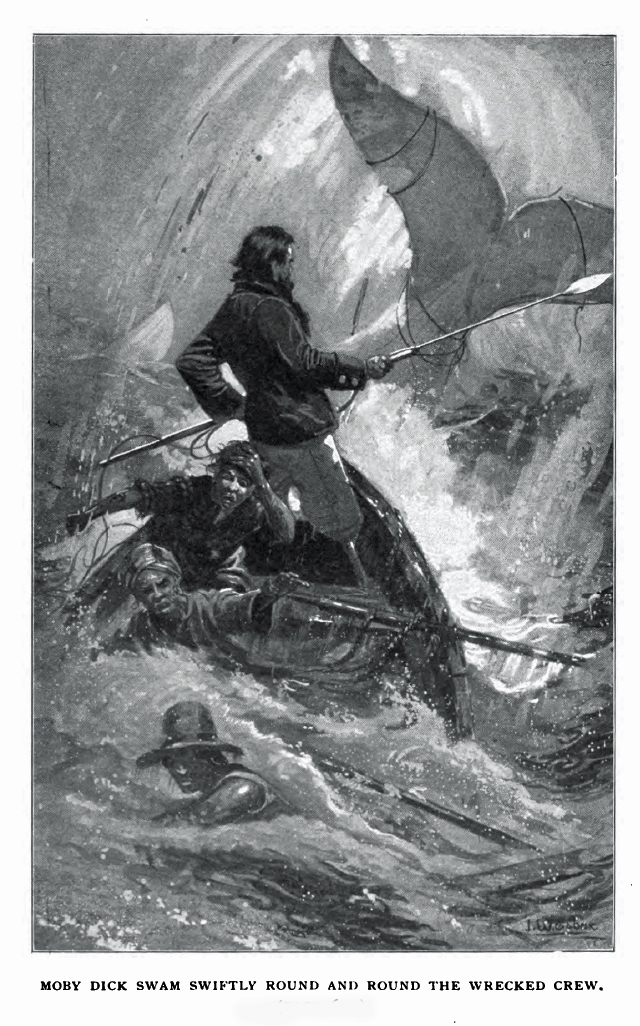

In his novel, The Crossing, Cormac McCarthy describes a scene where the two boys, having just crossed the border into Mexico, come into the company of an old man and ask him directions to the ranch of which they seek.

The old man proceeded to sketch in the dust streams and promontories and pueblos and mountain ranges. He commenced to draw trees and houses. Clouds. A bird. He penciled in the horsemen themselves doubled upon their mount. Billy leaned forward from time to time to question the measure of some part of their route whereupon the old man would turn to squint at the horse standing in the street and give an answer in hours.

All the while there sat watching on a bench a few feet away four men dressed in ancient and sunfaded suits. When the old man had gone, the men on the bench began to laugh.

Es un fantasma, they said.

One of the men threw up his hands. He said that what they beheld was but a decoration. He said that anyway it was not so much a question of a correct map but of any map at all. He said that in that country were fires and earthquakes and floods and that one needed to know the country itself and not simply the landmarks therein.

He went on to say that the boys could hardly be expected to apportion credence in the matter of the map. He said that in any case a bad map was worse than no map at all for it engendered in the traveler a false confidence and might easily cause him to set aside those instincts which would otherwise guide him if he would but place himself in their care. He said that to follow a false map was to invite disaster. He gestured at the sketching in the dirt. As if to invite them to behold its futility.

Another man on the bench nodded his agreement in this and said that the map in question was a folly and that the dogs in the street would piss upon it. But another man only smiled and said that for that matter the dogs would piss upon their graves as well and how was this an argument?”

And yet.

The last man gestured. He said that plans were one thing and journeys another. He said it was a mistake to discount the good will inherent in the old man’s desire to guide them for it too must be taken into account and would in itself lend strength and resolution to them in their journey.

A Bad Map is Worse than No Map at All

On Saturday, January 5th 2019, I issued what turned out to be the most blown avalanche forecast of my 20-year career. And not by a little. I stated that the avalanche danger in the backcountry was LOW. By the end of the day, we heard about nine skier-triggered avalanches with seven people caught and carried in separate events, with one visit to the emergency room. One might imagine the unspoken conversations of the slid skiers that day prior to the incident while noting the significant transport of wind drifted snow (on top of weak diurnal facets no less) - “Are you gonna believe Hardesty’s Low...or your own lying eyes?” They followed the bad map.

And this brought about great introspection:

- What are the goals of a forecast?

- Why do we get it wrong?

Why do forecasters blow a forecast and what does it mean to be wrong?

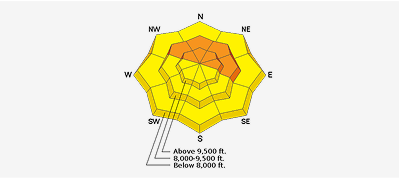

First, let’s tackle the second question - What does it mean to be wrong? This is best understood by looking at what “It” means. Undoubtedly, this means the forecast, but what part of the forecast? Is it the Bottom Line? Or can it be more than that? The bottom line is an aggregation of the devil and the details. It’s comprised of avalanche problems, location (aspect/elevation/slope specific details), likelihood (sensitivity, spatial distribution), size, and stability trend.

Below are just a couple examples of getting it wrong:

Right avalanche problem, wrong location.

Right avalanche problem, wrong likelihood.

Right avalanche problem, wrong size.

Right avalanche problem, wrong trend.

Right avalanche problem, wrong trend.

Right Process Wrong Outcome?

Sidney Dekker, Annie Duke and others encourage shedding the hindsight bias in favor of looking at what may have been a reasonable judgement with the facts, experience, and motivations at hand. In poker, if I hold three kings, I will almost always bet the farm. It may be that my opponent holds four 2s; but most would make my bet again ten times out of ten. This is a reasonable and understandable judgment call prior to knowing the outcome.

Annie Duke discriminates between poker and chess where the first involves uncertainty while the second does not. Mathematics is not a forecast and visa versa. The key point here, in trying to answer the question What does it Mean to be Wrong, should move upstream from the confluence to gauge the difference between two blown forecasts - one with the right process and the other without.

The more interesting question is Why Do Forecasters Blow the Forecast? The reasons avalanche forecasters blow the forecast are three-fold.

They Blew the Weather Forecast:

If they blow the weather forecast, then they are likely to blow the avalanche forecast. Expect 2” of snow with no wind but instead receive 12” with moderate wind? Hmmm. Expect overcast skies but instead see greenhousing? Yep, blew that one too. This is why forecasters often hedge and write words such as may, possible, probable: you get the picture.

If they blow the weather forecast, then they are likely to blow the avalanche forecast. Expect 2” of snow with no wind but instead receive 12” with moderate wind? Hmmm. Expect overcast skies but instead see greenhousing? Yep, blew that one too. This is why forecasters often hedge and write words such as may, possible, probable: you get the picture.

They Misunderstood the Nature of the Snowpack

There are myriad reasons here: lack of data or field time; inexperience; failure to appreciate the complexity or to adequately view “non-events” with suspicion.

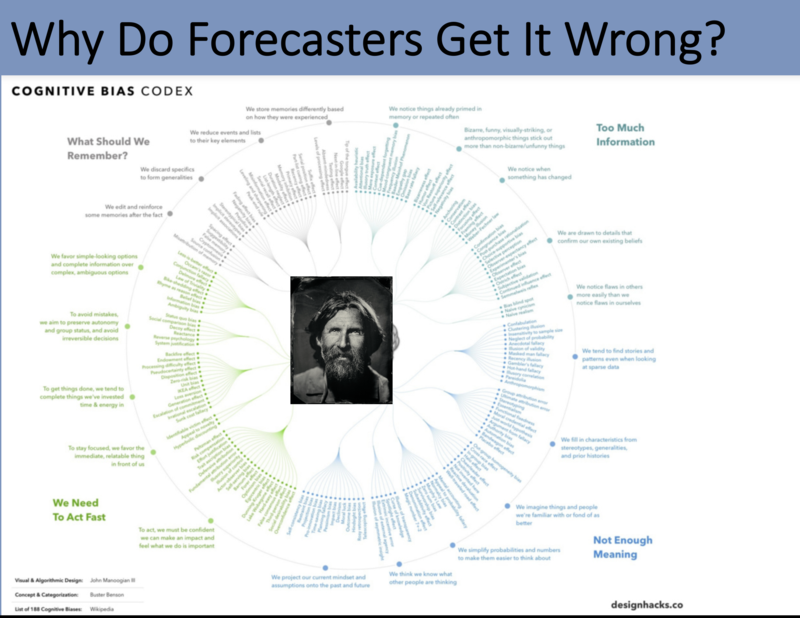

They Misunderstood the Nature of Themselves

It should be recognized that forecasters may blow the forecast in spite of themselves. Much of the literature examining the “human factor” in recent years may also be applied to the forecaster. Some of the heuristics and biases are the same.

See a quick list below –

Ego/Reputation - Hate to Cry Wolf

Impatience/Message Fatigue

Ego (not appreciating uncertainty)

Anchored to previous forecast (Expert Halo?) or efforts to be consistent

Overcompensate for yesterday’s blown forecast

Cognitive Dissonance – Discounting contradictory evidence

Personal Near Miss or Fatality in Zone

Consistently Over Forecast (“I’ve been burned too many times”)

(Benson/Manogian)

What’s the Goal Here?

This brings about understanding the goals and objectives of the forecast. Is the goal to save lives or is the goal to accurately portray the conditions as they are? If the only goal is to save lives, then most mountain passes and highways would be closed from November to May. But we know this is not the case. If the goal is to portray conditions as they are and will be, then we are bound to make mistakes. And we know that it must be worth it for the greater public good because agencies employ people to make judgment calls and forecasts. And yet there is often great tension between the two. The answer, of course, is both.

Which brings us to the economist Peter Donner’s paper Bias, Variance, and Loss. Donner hits upon a number of interesting topics, not the least of which involves the asymmetry of loss in regards to bias. Overforecasting can be expensive (margins) and often leads to a deaf audience...and if a tool is not a tool, then it is a rock....and rocks should be thrown through windows. Just ask Homeland Security about their Homeland Security Advisory System aka the “Terror Alert Level” (lasted only from 2003 to 2011 because they never used the bottom two levels..and people stopped paying attention!) Underforecasting leads to...well, it leads to Jan 5, 2019 in the Wasatch, the nine skier triggered avalanches and the Blue Ice incident. Blown forecasts have consequences.

What led to the blown forecast?

A good sampling of “all of the above”. I’ll briefly address each category.

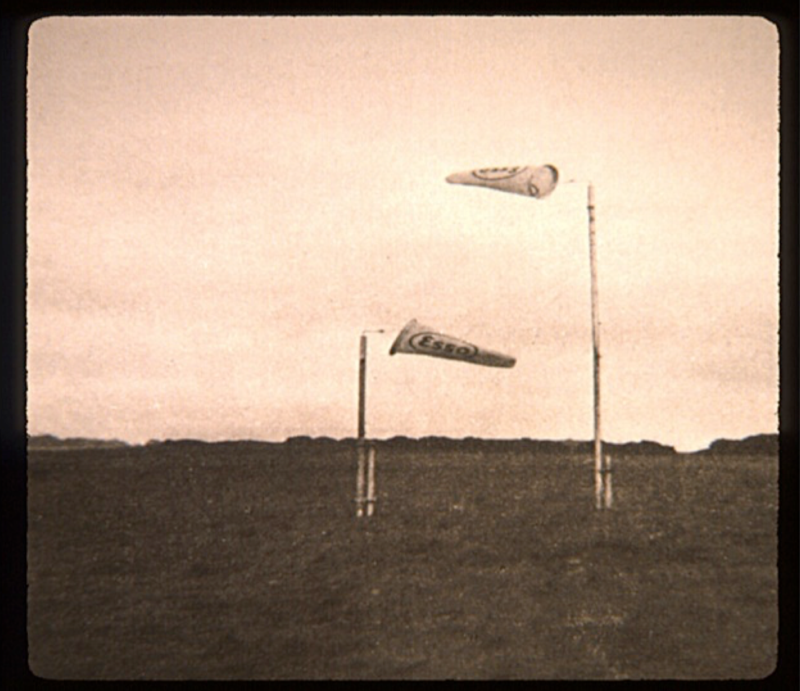

I blew the weather forecast. The southwest winds arrived earlier and stronger than I expected.

I misunderstood the Nature of the Snowpack. The range had been hammered by north and east winds the previous few days. South faces held bulletproof suncrusts. I pictured wind damage and-only later - areas of wind slab.

I misunderstood the Nature of the Myself. We’d had consensus for my previous day’s Low danger and I was probably anchored to that. I knew we’d be at Considerable the next day and felt a Low-to-Considerable jump would well capture that danger trend. I also spiraled into forecasting philosophy at 5:30am, ‘We really don’t use Low and Extreme as much as we should.’

I blew the weather forecast. The southwest winds arrived earlier and stronger than I expected.

I misunderstood the Nature of the Snowpack. The range had been hammered by north and east winds the previous few days. South faces held bulletproof suncrusts. I pictured wind damage and-only later - areas of wind slab.

I misunderstood the Nature of the Myself. We’d had consensus for my previous day’s Low danger and I was probably anchored to that. I knew we’d be at Considerable the next day and felt a Low-to-Considerable jump would well capture that danger trend. I also spiraled into forecasting philosophy at 5:30am, ‘We really don’t use Low and Extreme as much as we should.’

A quick digression on Low. It seems to me that Low is different than the other forecast danger ratings insofar as how many adjust their habits and protocols, and not necessarily in a good way. Risk compensation (homeostasis) is not a new idea to the avalanche world but when that “glowing green orb” is at the top of the page, something changes in the chemistry of the brain. We may more commonly travel solo, become lax in our travel habits, and seek out more unforgiving terrain where - pound for pound - even a small harmless avalanche is not so harmless. That traumatic injury becomes the result.

And in perception, I wonder if Low reduces the five point scale to a binary one: it’s either dangerous or it’s not...and now it’s viewed as “ not dangerous”. In other words what has been an unacceptable risk is now acceptable. Similarly, I wonder that Low may convey more certainty than all the other ratings. And perhaps it should. In a recent study on forecast verification last year, Statham, Holecsi, and Shandro found that Low was the most accurate at 84%...and things became less accurate as the forecast danger increased. Flipped upside down, this points out that one in every six forecast Low ratings is wrong. How’s that for spin?

What to do?

The list is certainly incomplete but considerations for both the forecaster and the public -

For the forecaster in the hotseat –

- Communicate/Gain Consensus When Possible

- Do a Pre-Mortem Before You Publish the Forecast (How will you be wrong and What will happen?)

- Appreciate and Communicate Uncertainty

- Remember It’s a Forecast (not Back, Now, or Wishcast)

- Choose Impact over Criteria (Hurricane Sandy/Katrina)

- Remember the Asymmetric costs between blown over/under forecasting

- Psychology of Glowing Green Orb of LOW danger and how it may be viewed by thepublic

- Who’s the Audience? 32% only use the bottom line (St Claire, Finn, Haegeli)

- Know that once in awhile you’re going to make mistakes.... And when you do, own them. (Just try not to make the same mistakes)

The bottom line for the public is below –

- The Forecast is Guidance Not Gospel

- Know Who’s in the Forecast Office

- Choose Terrain in Case you/forecaster is wrong

- Appreciate the Uncertainty (esp with the Extra Caution problems)

- Forecast is only ONE of ALPTRUTH

And yet.

The last man gestured. He said that plans were one thing and journeys another. He said it was a mistake to discount the good will inherent in the old man’s desire to guide them for it too must be taken into account and would in itself lend strength and resolution to them in their journey.

The last man gestured. He said that plans were one thing and journeys another. He said it was a mistake to discount the good will inherent in the old man’s desire to guide them for it too must be taken into account and would in itself lend strength and resolution to them in their journey.

Thanks to all the forecasters who contributed their thoughts and well earned wisdom to the piece. To Laura Maguire, Russ Costa, Jenna Malone, Zinnia Wilson, and many others who added to and clarified many of the points herein. The essay has greatly improved through their efforts.

Thanks also to Vlad and Jackie (just married!), Greg Gagne, Russ Costa, Laura Maguire, Derek DeBruin and of course Ben Bombard, producer of the Utah Avalanche Center podcast, found HERE.

Great article Drew. I happen to read this the same day I am taking the avalanche research program on-line survey.

There is a section of the survey where they ask if the route finding simulations are helpful in digesting the forecast. I said yes. Then it asks if they should be included with forecasts. I said no. The survey does not give you the option to explain your answers so I thought I would put it here. I could only imagine someone getting hurt after reading a forecast and making a route decision from an attached simulator and blaming the forecast for actually reinforcing the route they take for that day. I think is goes along with your comment about Low hazard forecasts...."And in perception, I wonder if Low reduces the five point scale to a binary one: it’s either dangerous or it’s not...and now it’s viewed as “ not dangerous”. In other words what has been an unacceptable risk is now acceptable. Similarly, I wonder that Low may convey more certainty than all the other ratings" I think route simulations are a great learning tool to help understand how to read a forecast, but adding them to the actual forecasts is a slippery slope any may give people more certainty to which route to take while causing them to back off the use of the five point scale.

johnadams218@co... (not verified)

Sun, 4/12/2020

Drew,

Just a note of thanks for the wonderful stories and lessons today. My best to everyone at the center and your continued work.

Willis Richardson (not verified)

Sun, 4/12/2020

Drew, thank you for being a huge part of the culture here in salt lake. For owning and sharing our mistakes and hopefully, becoming better for it. And truly thanks for being our friend when we needed it most!

Jackie (not verified)

Mon, 4/13/2020