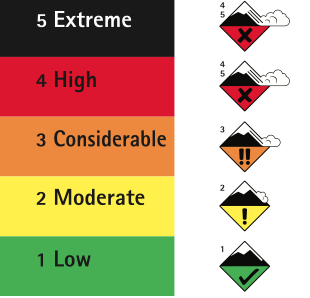

Who was it that said, "Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the other ones." Mark Twain? Rather, Winston Churchill, just after the war, and it's likely he borrowed it from someone else. (Perhaps Twain, again.) I think it's the same with our Avalanche Danger Ratings.

At the Black Diamond Fireside Chat a couple weeks ago, I had a surprise for those who showed up. I guessed that most of them had come to learn something from me...but I told them that I was going to turn the tables...and learn something from them. I gave them two scenarios and asked them to be the forecaster - and tell me what the danger rating was for each day. (Surprisingly, no one left.) But I gave them a crash course first....

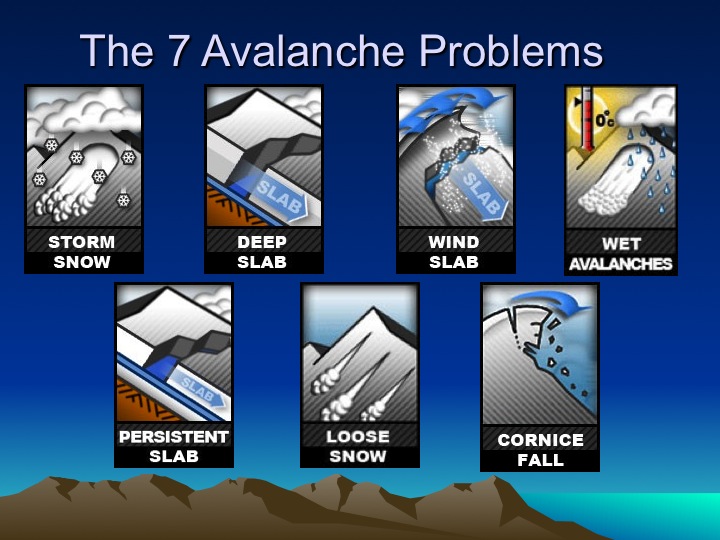

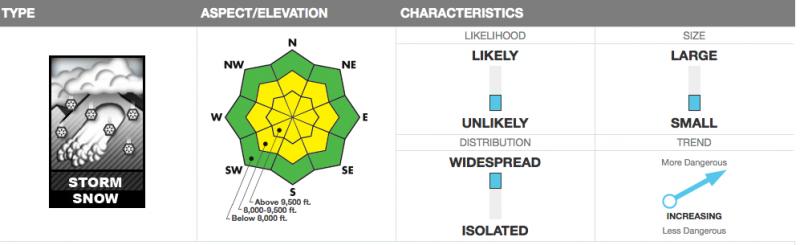

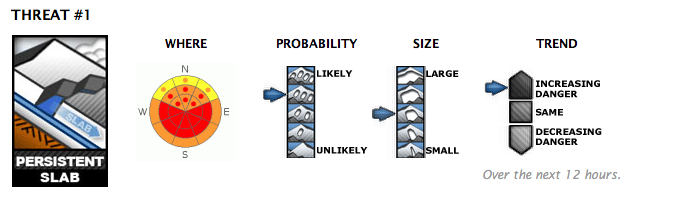

I pulled out a flip chart/dry erase board and launched into a discourse about how we come up with our danger ratings and how we looked at each avalanche problem. With each avalanche problem (Storm Slab, Deep Slab, Persistent Slab, etc), we would rate it on a variety of factors (of which I'll go into in more detail below):

- The Likelihood that one could trigger the slide. Also loosely described as Probability. (What are the odds?)

- The Size of the Expected Avalanche (best based upon the Destructive Scale)

- The Spatial Distribution (isolated, localized, widespread) to include our danger rose aspect/elevation diagram

- Trend (increasing, decreasing, same)

For us at the Utah Avalanche Center, it has looked like this -

Or This:

LIKELIHOOD

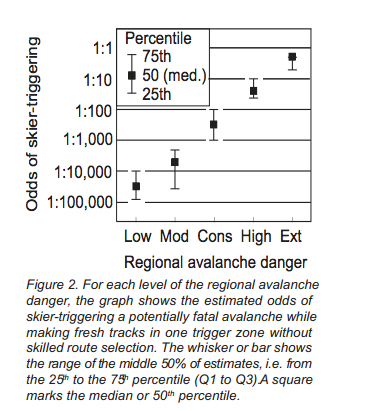

In the late 2000s, Dr. Bruce Jamieson from ASARC (an avalanche research group affiliated with the University of Calgary) sent out a survey to avalanche professionals in North America. Lacking good 'data', he wanted to gather thoughts on how likely a backcountry skier would be caught, carried, and killed in an avalanche based upon each danger rating. I remember receiving the survey. His results (it was a collaboration with the prolific Swiss avalanche researcher Dr. Juerg Schweizer and Jamieson's own grad student at the time Cora Shea) are below.

The authors go on to explain, "The calculated avalanche risk from skiing increases roughly 10-fold with each level of regional avalanche danger. This follows from the approximate 10-fold increase in triggering probability when the regional danger increases by one level (Figure 2, based on the survey).

(Jamieson, Schweizer, Shea, 2009. Simple Calculations of Avalanche Risk for Backcountry Skiing, Proceedings of the International Snow Science Workshop 2009)

In the "olden days", the bottom line danger rating typically fell to this metric - probability - and we had terms like "unlikely", "possible", "probable", "likely", and "certain". Typically, CONSIDERABLE hazard was when you transitioned to natural avalanches becoming "possible". This metric didn't work very well: Imagine if you were offered $10 million dollars to play Russian Roulette. Would it change anything if I told you ahead of time how many rounds were in the chamber? Would you make your decision on that? What if I told you what kind of rounds were in the chamber - paper spit wads, bbs, bullets, at 105mm howitzer shell, a nuclear bomb.

Other problems arose from odds - I asked the participants at Black Diamond what they thought the odds were (%) for human triggered slides with danger levels - below were there general thoughts -

Low - 1-5%

Moderate - 25-35%

Considerable - easily better than even chance - 60-65%

High - 75-85%

Extreme - 90-100%

The biggest take-home for me was the discrepancy between Moderate (35%) to Considerable (60%). What makes up the difference? After all, most people are out in the backcountry during periods of Moderate to Considerable hazard. Where does that 25% go?

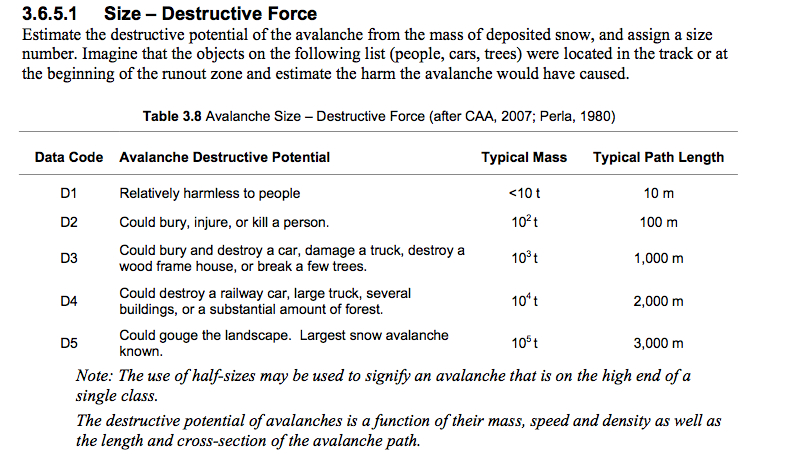

SIZE

Size matters. And so do the consequences. Some of this has to do with terrain choices (ie - are you above a gentle runout or a bergschrund?) but ultimately it comes down to what we call the Destructive Scale. The following is what we use to communicate among 'professionals', as taken by the SWAG (Snow, Weather, and Avalanche Guidelines; Greene, et al).

DISTRIBUTION

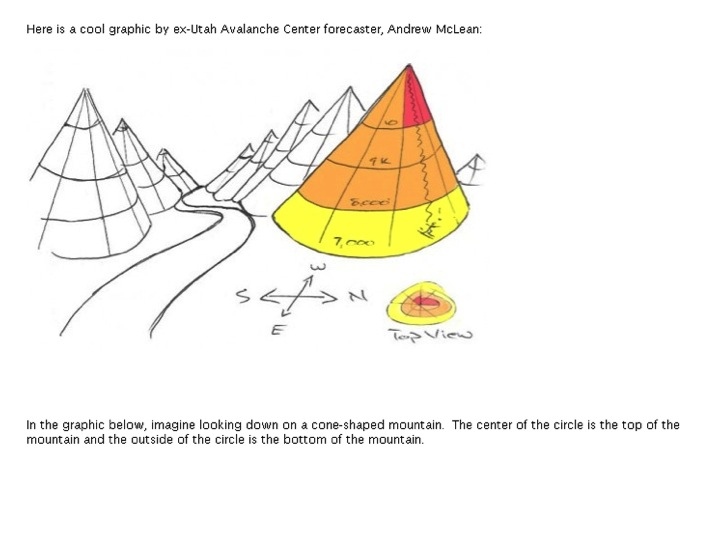

This comes down to how isolated or widespread the avalanche problem is. A few years ago, Andrew McLean sketched a pretty good 3d depiction of aof what our danger rose would look like. (See below). But to a great degree, it also indicates how pockety trigger points might be and or how pockety the wind slabs or surface hoar persistent slabs might be within that aspect/elevation 'square'.

DON'T WATCH THE VIDEO YET!

(DON'T WATCH THE VIDEO YET!)

Now the Good Stuff -

With the audience now well primed, I handed out index cards to each person and had them write Scenario A on one side and Scenario B on the other...and then I showed them two scenarios for which they would write down the day's danger rating (what we call 'Hind-casting' or 'Back-casting'). It was key that the participants did not talk amongst themselves. (See the Wisdom of Crowds).

Here they are -

Scenario A (which, as it turned out, was what I had observed that very day) photo below.

I had stumbled upon numerous of these natural soft slabs during the day, triggered by wind/heating. These were 4" deep and 30' wide on a variety of sunny aspects. Widespread. The participants went through their mental checklist and wrote down the danger rating.

Scenario B - OK NOW WATCH THE VIDEO

I tell them that this took place in the San Juans of southern Colorado which could house how many Wasatch Ranges? and that not only was he the 7th skier on the slope, that he skied in between all the other lines, but - get this - his was the only avalanche triggered in the entire range that day. Again, the participants hemmed and hawed over what to write down.

I then had an assistant come up to the dry erase board and she wrote down people's answers under Scenario A and B. While there was some scattershot, the answers were clear, striking, and - dangerously misleading. Huh? Clear in hindsight, but dangerous as a forecast. BOTH WERE RATED MODERATE.

And therein lies the problem. A few years ago, I started looking into many of the accidents and fatalities from the intermountain west and found that most occurred when there was a Moderate hazard with what I am terming an "UNMANAGEABLE" avalanche type. This refers to those persistent or deep slab avalanche that is often accompanied by either a hard slab or situation where remotely triggered slides are possible.

MANAGEABLE - loose snow, storm slabs, wind slabs, most wet snow slides, cornice - where (in 'MODERATE' anyway), they're triggered at your feet or sled.

UNMANAGEABLE - persistent and deep slab avalanches where you may trigger them remotely, or when you're half-way down the slope, or if you're the 7th person on the slope. You are not intentionally triggering the slide. Predictable only in their unpredictability.

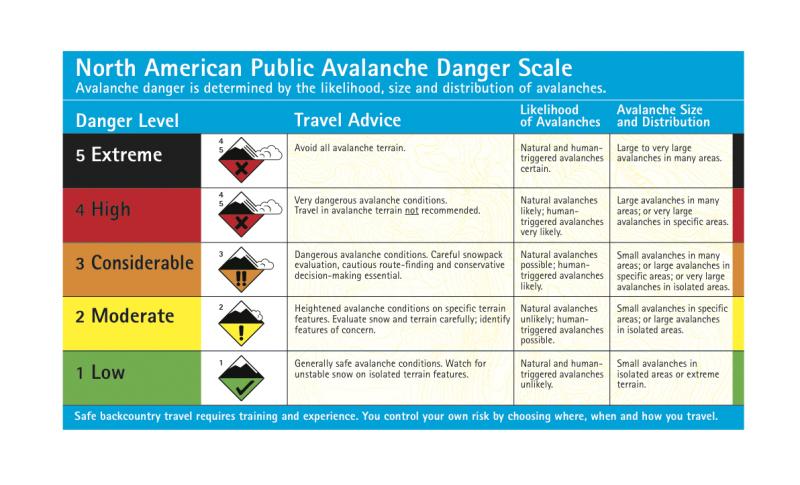

Below is the current danger scale, adopted a couple of years ago, that added size and distribution, but I feel that it still misses the mark. Read on...

Note how under Avalanche Size and Distribution it says, "Small avalanches in specific areas; or large avalanches in isolated areas." If you asked the guy in the film what he thought the danger was that day (tragically he died), he'd probably say, "HIGH". What's difficult is that we're trying to have it both ways. Do you want to get thrown into a fishtank with 6 blacktip sharks that might nibble your toes....OR.....a single great white...and it's unclear how recently he's fed. Maybe there's blood in the water.

And so what we've found over the years is that we don't have a snow problem - we usually have a pretty good idea of what's going on with the snowpack...we have a communication problem. And it's not just us - remember the old Homeland Security Agency domestic threat scale you used to hear over the loudspeaker at the airports and cost millions? Yep, they scrapped that too.....

A few years ago, I proposed a modifier - X - to be added to the danger rating when the avalanche problem was more than what met the eye; in other words, Unmanageable. That article, printed in the Avalanche Review, is below -

X: death or serious injury may occur Story and photo by Drew Hardesty

What’s the danger? Moderate? Considerable? Scary Moderate? How best to convey this information to the Tier 1 user? I’ve never felt comfortable with this, particularly when deep slab instability persists for weeks, even months. For Tier 2 information (the actual avalanche advisory), I like our current method in Utah of separating out the individual “threats” (wind slab, persistent slab, wet avalanche, loose snow, etc) and rating them on probability, size, trend, and distribution (see TAR 24/4). But boiling it down into one word for a danger rating? Not so easy, especially with Moderate. For many users, it’s the new Low! (photo of remote by Jonathan Cracroft)

Let’s look more closely at Moderate danger, where the devil’s in the details. You and I will choose our terrain and manage our clients differently when presented with different types of avalanche problems. It comes down to what Roger Atkins and others term “avalanche character.” Implicit in its character is its “manageability.” Loose snow, shallower soft slabs, and storm-snow avalanches can often be “manageable” hazards; that is to say they respond to ski cuts and cornice drops and propagate from your skis, board, or sled. Hard slabs, deep-slab instability, remotely triggered slides – these are arguably “unmanageable” hazards. Yet, there are times when these hazards are rated as Moderate simply because they lack the previous (day’s/ week’s/month’s) sensitivity and spatial distribution. Maintaining the Considerable hazard for the public risks the perception of crying wolf.

In the climbing world, a clean, well- protected 5.9 is rated 5.9 due to its difficulty. What about that same route when it’s a tower of loose and friable rock with few options for protection? It’s a 5.9X. The X universally denotes that “serious injury or death may occur.” Here, consequences pair with difficulty to give the climber the complete picture. When one sees the X, one is required to pause and give it some thought. If a mistake is made, consequences are significant.

When the Tier 1 user sees Moderate, they understand that potentially “dangerous avalanche conditions exist on some terrain features.” Or “human-triggered avalanches are possible. Natural avalanches are unlikely.” And that they should “evaluate the snow and terrain carefully and use good travel habits.”

When they’ve been trained to see Moderate X, they get a different picture. When the sensitivity and distribution doesn’t warrant a Considerable rating, a Moderate X conveys the potential consequence in no uncertain terms. Again, X is wholly a function of the avalanche character, size/consequence, and manageability. And this makes all the difference – that not all Moderates are created equal – a lesson that some have learned with tragic consequences.

Spatial distribution of the danger also has interesting parallels in the climbing world. By most accounts, a single pitch route that is mostly 5.7 with one move of 5.9 is rated as a 5.9. How do you rate the overall danger if it’s Moderate with “one move of” Considerable? Do you follow the climbing paradigm? Perhaps.

The X may be most useful as a modifier for Moderate, but I can see many uses for it in the higher danger ratings as well. Thus far, I’ve gotten a lot of good feedback from many Tier 1, 2, and 3 users in the Wasatch on this model. And I feel strongly that it’s not whether we like it or not, but whether the public at large likes it. If it’s a simple, intuitive, and useful tool for the public to make good choices in the mountains, then, particularly at this time of evolution with the North American danger scale, we officially utilize the subscript or modifier X to wholly convey the bottom line when only one word counts.

Would this work? Maybe, and maybe not. What other ideas are out there?

Bottom Line here is don't be fooled by what we sometimes call a MODERATE danger (for now). Low probability high consequence will kill you well before high probability low consequence. Keep an eye out when there's mention of Persistent or Deep Slabs.

Your comments are encouraged -

Drew Hardesty

Forecaster, Utah Avalanche Center

COMMENTS FROM THE PUBLIC

Hey Drew -

Once again, really good stuff from you. I really appreciated reading this entry and it must have taken some time to put together. Hopefully you'll get some comments as well as a conversation going. I don't have much to add as you've covered things pretty well. What is interesting is the focus on Moderate - rather than Considerable (which seems to be the rating that confuses most of us.) What I especially don't like about the current danger rating is the level is trying to convey (1) likelihood, and (2) size/distribution. As you clearly point out, these are often entirely unrelated (especially when we have a PWL.) I use the danger level only for the likelihood (perhaps I'm old school), and think about consequences specific to each slope. (I backed off a steep slope back in mid January on a largely Low hazard day because of the consequences of a slide in that area.) I'm sure alot of smart, experienced people have thought long and hard about how to come up with a new scale that addresses the many different factors involved with risks of avalanches, so I'm not even going to pretend that I could suggest something better. For now we really still have the 1-dimensional scale with the 5 different ratings. We really need something like a second scale - or x-rating as you suggest - to better assign some sort of more useful metric we can use for our risk management. It seems like the past two seasons have plagued us with persistent/deep slabs much more so than we are used to (certainly last season.), and like so many others have done I have made that second mental note of the type of avalanche issues we are dealing with and have planned accordingly. I think you have done a nice job in your forecasts of trying to convey these more difficult issues outside of likelihood and I suspect this burden will continue to fall onto you and the other forecasters. I'm sure there have been some forecasting days where you really didn't want to say what the danger level was, but rather simply describe the hazard and let people make the connections themselves. Education is obviously key as well. As I said at the beginning, I don't really have much to add, but I really appreciated reading this and am hopeful it will further the conversation. Thanks again for putting it together. //greg

Drew,

I very much agree with your assessment of the very difficult danger rating when there are low probability, high consequence conditions in the snow pack. Being a climber I certainly approach a 5.9 much differently than I would a 5.9R or X. Likewise, I choose my ski routes much differently when there are lingering deep slab issues within the snow. I feel as though you guys at the Utah Avalanche Center do a phenomenal job, day in and day out, of presenting the various hazards that exist in the Wasatch. Being a person who reads the avy report everyday and studies each observation, as well as getting out and skiing the backcountry regularly, it becomes easier to make sound judgement calls on which slopes to avoid and when. However, I imagine that much of your argument for creating an X rating is to continue to develop the danger scale to make it as easy as possible for people to quickly and easily understand the underlying consequences that are present when they decide to ski in the backcountry. When I look at a climbing guide and see an X, it very quickly makes me understand that if I get on that route I need to be damn sure I have the ability to climb the route without falling, and that a mistake could spell certain doom. Conversely, if I were to be someone who didn't keep track of the avalanche conditions everyday throughout the season, I could quickly look at the danger rating in the morning to see, moderate X, and understand that there is the potential for unsurvivable avalanches to occur, and plan my day accordingly. In the end, I think that anything that can be done to continue to make it easier for people, especially the tier one user, to recognize the consequences of skiing in avalanche terrain, the better. I very much appreciate all of the work that you and your colleagues do to educate me and others each day. I often look at other avalanche advisories around the country, which makes me feel very lucky to live in the Wasatch, where the avalanche report is far superior. Thank You, Jeff

Drew,

Drew -

I like the x modifier. It's been mentioned that a non climber may not understand it, but it took me 30 seconds to explain it to my partner Matt, he is not a climber and he got it and thought it should be used. Keep pushing for the x! I will help in any way I can. At Rogers Pass they merge consequences into the forecast and there are too many days where it is considerable because of that, where the probability is only mod.

Todd

FORECASTER COMMENTS:

Always, always appreciate your thoughts here...and particularly by approaching it from a different path (ie- the medical profession).

Hi Drew,