Observer Name

UAC Staff

Observation Date

Sunday, February 7, 2021

Avalanche Date

Saturday, February 6, 2021

Region

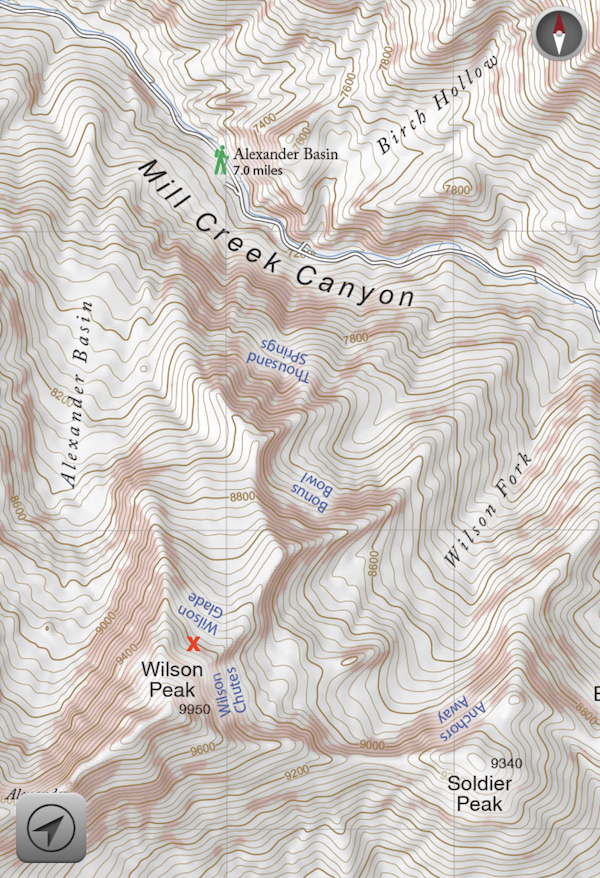

Salt Lake » Mill Creek Canyon » Wilson Fork » Wilson Glade

Location Name or Route

Wilson Glade

Elevation

9,600'

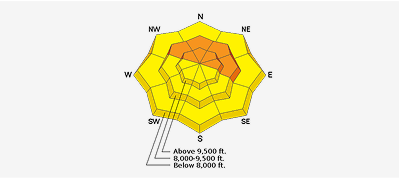

Aspect

Northeast

Slope Angle

31°

Trigger

Skier

Trigger: additional info

Unintentionally Triggered

Avalanche Type

Hard Slab

Avalanche Problem

Persistent Weak Layer

Weak Layer

Facets

Depth

3.5'

Width

1,000'

Vertical

400'

Caught

7

Carried

7

Buried - Partly

1

Buried - Fully

6

Injured

1

Killed

4

Accident and Rescue Summary

Synopsis: On the morning of February 6, 2021, two different groups (eight people total) went to ski in the Wilson Glades area of Alexander Basin on the north side of Wilson Peak in Millcreek Canyon. Both groups were ascending when the avalanche happened. Group A was near the top, and Group B was below. This avalanche was likely human triggered, but it cannot be determined by whom. Six people were caught and fully buried. Two of them survived, and four did not.

Note: Several take-home points and lessons are included at the very bottom.

Their names are grouped into their respective groups below. Each party was traveling separately and had not seen or talked to each other that day.

Group A - Chris, Sarah, Louis, Thomas, Steve

Group B - Nate, Ethan, Steph

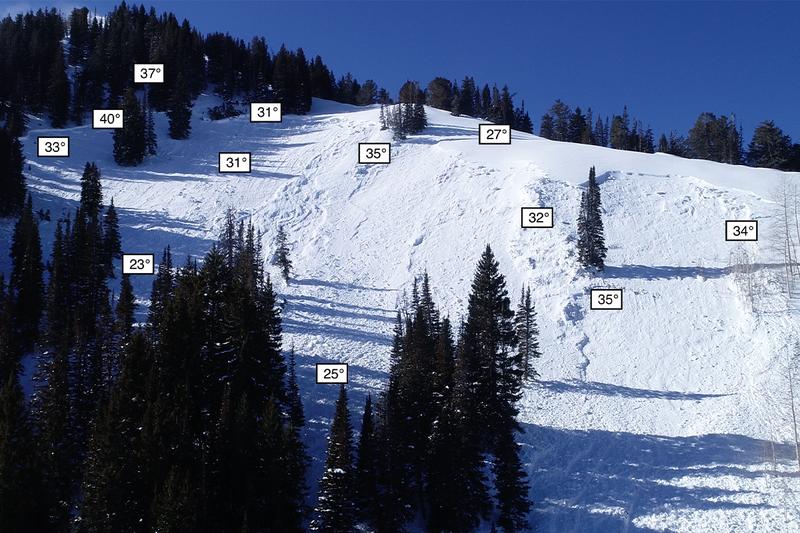

Photo of the avalanche crown, which was 3-4 feet deep and close to 1,000 feet wide

Group A started at the Butler Fork trailhead in Big Cottonwood Canyon (BCC) at approximately 0700. They used the Butler Fork trail to access a ridgeline between Soldier Peak and Wilson Peak with a plan to ski the Wilson Glades. While they knew that Wilson Glades was avalanche terrain, they considered it a safer option during HIGH avalanche danger. They thought any avalanches in that area would be “pockety” and did not think the entire slope would avalanche as it did.

While ascending Wilson Peak, Group A noticed a very large natural avalanche in the Wilson Chutes on the east-facing part of Wilson Peak. They posted a photo of this avalanche on Instagram and tagged the Utah Avalanche Center at 0833.

Group A reached the top of Wilson Peak (9,950 feet). At the top, they discussed how to ski Wilson Glades but never discussed if they should ski it or not. They discussed avoiding the steeper sections and going one-at-a-time with everyone participating in that discussion. No other party had been there that day, and they descended/skied the Wilson Glades one at a time. Once the group reached the bottom of the slope, they started breaking a trail back to the top to ski Wilson Glades again.

Group B approached the Wilson Glades from Millcreek Canyon starting at 0830. They began walking on skis from the end of the plowed road, approximately three miles to the Alexander Basin trailhead. They began breaking a trail uphill to the Wilson Glades drainage from that trailhead, just east of Alexander Basin. Group B saw several natural avalanches in Alexander Basin while ascending their route into the Wilson Glades. As Group B continued up Alexander Basin into the Wilson Glades, they all discussed the avalanche danger. They were all aware that the avalanche danger was rated HIGH for the day in that terrain.

Group B was aware that the Wilson Glades could avalanche, and their general plan for the day was to avoid avalanche terrain. Their specific travel plan was to ascend the Wilson Glades, stop at some point before the steeper section, and then discuss a plan for where to go and what to ski. Ethan and Steph were familiar with the area, while it was Nate’s first time skiing the Wilson Glades as he had just moved to Utah on January 1st. Both groups made observations of recent avalanche activity, but neither dug a snowpit to investigate the snowpack.

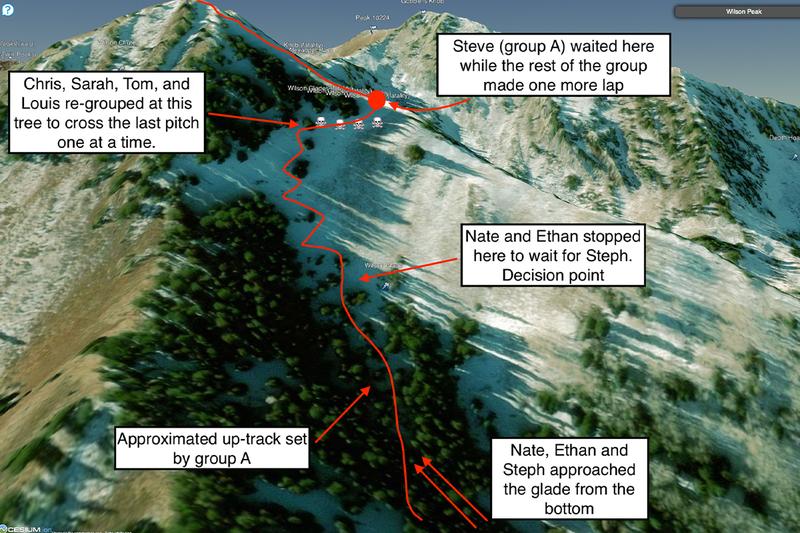

Group B reached the bottom of Wilson Glades and noted many tracks in the area and a recent skin/uphill track to the looker’s left (to the east). They followed the skin track uphill. When Nate and Ethan reached a point where they could see the steeper slopes above them, they waited in a sparse opening in the trees for Steph so they could discuss their plan for the day.

Meanwhile, Group A had skied the Wilson Glades three times totaling 14 tracks down the slope. After their second lap, Steve was tired and opted to wait somewhere above while the group made their third lap. After the third lap, their plan was to climb back up and descend into Big Cottonwood Canyon to the Butler Fork Trailhead, where they had started.

Photo of the slope minutes before the avalanche showing 14 sets of ski tracks taken three miles to the north. (D. Nix)

After Group A skied the slope for the third time, they transitioned back into uphill/walk mode and began climbing up their previously set skin track. The group traveled together until they reached the steepest part of their skin track, where they regrouped at a large tree to cross the last part of the slope one at a time as they had done two times before. (see the image below)

Image showing an overview of where people were right before the avalanche happened.

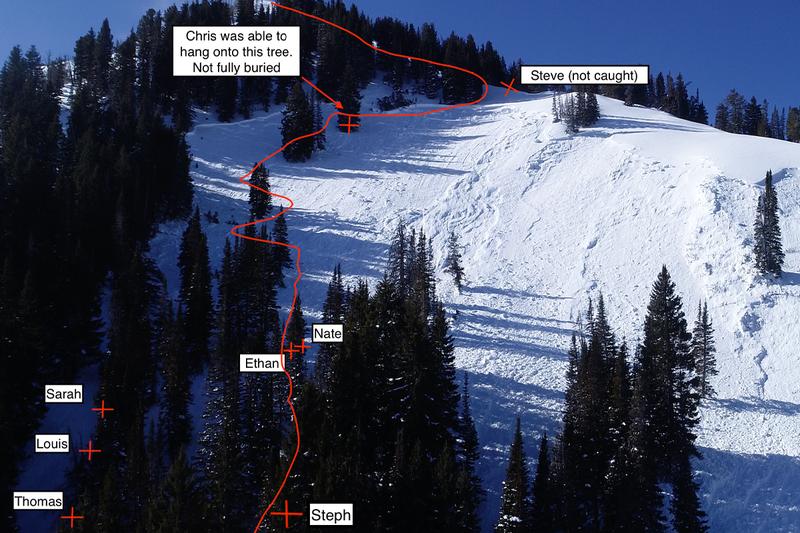

While the four people in Group A were grouped together on the skin track at the large tree, Chris was in front, and he reported hearing something that sounded like an earthquake. The avalanche broke approximately 30 feet above them, and Sarah, Thomas, and Louis were swept downhill in the avalanche. Chris lunged for a tree and hit it so hard that the “wind was knocked out of him.” He was able to hang onto it and felt immense pressure while the avalanche swept over him. He saw nothing but blackness for 2-3 seconds. Both skis were ripped off his feet, and he was left hanging in the tree above the bed surface after the avalanche passed. Note - It is very rare that people can hang onto trees as Chris did.

At this point, neither group was aware of the other aside from Group B seeing Group A’s ski tracks and skin track.

Photo looking down the path. The uphill skin track was to the right of the nearest tree on the right side of the image (B. Tremper).

Just as most of Group A was caught in the avalanche, Ethan and Nate, in Group B, were waiting together for Steph to catch up when they looked up and saw a wall of snow coming at them (see the image above for their approximate location). Ethan and Nate had only been stopped for roughly 15-30 seconds before they saw the avalanche, and all three were caught and fully buried.

In Group A, Chris dropped out of the tree he had been hanging onto and screamed for Steve (who was on the ridge above) to come down. Chris turned his transceiver to receive and began searching downhill in a zig-zag pattern on foot.

Steve heard the yelling and skied down as Chris was acquiring the first transceiver signal. Chris followed the signal to the lowest number and deployed his avalanche probe. His probe struck a person on the first strike, and both Chris and Steve started digging. They dug roughly 4-6 feet deep, expecting to find a member of their group but were surprised when they uncovered Nate (Group B), someone they didn’t know or recognize, who was unconscious but breathing. As Nate gained consciousness, they told him to get out his shovel and turn off his transceiver.

At this point, Chris (Group A) called 911. He gave brief details about the avalanche and their location and hung up. Subsequently, 911 dispatch called Chris numerous times, but he didn't pick up as he was trying to find the remaining party members. There was some confusion with multiple calls, but the official time when 911 dispatch determined there had been an avalanche was 1140.

From group B, Nate initially thought the avalanche was moving slowly and did not think it would reach them. Then he remembers the wall of snow overtaking him and Ethan, moving them only a short distance downhill, and being buried as the debris stopped moving. He quickly lost consciousness. After regaining consciousness, Nate’s next memory was assembling his shovel and turning his transceiver off.

This photo shows everyone’s approximate locations when the avalanche stopped. The uphill skin track used three times is shown with a red line. The uphill skin track was taken out by the avalanche.

While Nate (Group B) assembled his shovel, Chris and Steve started to uncover Ethan (Group B), another skier they didn’t recognize and were surprised to see. Ethan was buried about two feet (east) from Nate at the same depth. By this point, Nate had recovered enough to help with the shoveling. They found Ethan unconscious but breathing and uncovered him just enough to turn off his transceiver. Ethan remained unconscious and breathing, and they left him partially buried, still anchored to his skis under the snow to search for the others.

After turning off Ethan’s (Group B) transceiver, Chris walked in a circle around Ethan and acquired another transceiver signal. They followed the signal to another buried person who was approximately 150 feet to the east at about the same elevation. They located Sarah (Group A), Chris’s significant other, under two to four feet snow. She was not breathing and did not have a pulse. They cleared her airway and gave rescue breaths and chest compressions. They also turned off her beacon. Chris continued CPR while Steve (Group A) and Nate (Group B) began searching for the next person.

Steve and Nate next located Louis (Group A) just downhill from Sarah. He was buried four to six feet deep. He was not breathing and did not have a pulse, and no further life-saving measures were taken. They turned off Louis’ beacon and continued searching for another person. After Louis was uncovered, Chris stopped performing CPR on Sarah and rejoined Nate and Steve to search for others.

At this point, Ethan (Group B) was regaining consciousness and screaming. Nate returned to Ethan, who was showing signs of hypothermia and in a lot of pain. Nate finished digging Ethan out of the debris and gave him extra warm layers and food/water. Then Nate left Ethan again to help Chris and Steve.

Steve, Nate, and Chris began searching once again and got another transceiver signal. They found Thomas (group A) buried 2-4 deep. They cleared his airway, but he was not breathing and did not have a pulse, and no further life-saving measures were taken. Sarah, Louis, and Thomas were all buried approximately 30 feet apart from each other down the fall line. Their burial locations are marked in the image above.

Nate, a registered nurse, was very concerned about Ethan’s condition and again returned to his location to provide care to Ethan.

After finding Thomas, Chris and Steve acquired another transceiver signal. They found Steph buried four to six feet deep in an upright position with her feet downhill. She was approximately 100 feet to the west and slightly downhill from Thomas. Nate rejoined and cleared her airway, but she was not breathing and did not have a pulse, and no further life-saving measures were taken. After uncovering Steph, Nate returned to Ethan and continued caring for him.

The left photo shows Dave Richards demonstrating how Ethan was positioned when he was found alive. Nate was recovered alive just to the right of Ethan. The right image with the backpack shows where one of the victims was buried.

These three photos show the burial depths of the other three victims.

This photo shows the proximity of the three victims from Group A. A skier (with a small x) is standing next to each burial location. All are oriented in line with the fall line about 30 feet apart.

By the time all six people had been dug out of the debris (two alive and four deceased), there were multiple helicopters circling above the scene with rescue personnel on-board. The survivors moved to a lower, open area where two search and rescue personnel were lowered from a helicopter via a hoist mechanism at 1340. (The initial dispatch notification of this avalanche was 1140.)

Note about skis - Both Chris’ skis were ripped off his feet as he clung to a tree. Thomas had one ski attached to his feet. All the other people had both skis still attached to their feet when they were buried, which may have contributed to deeper burials. All had tech/pin style bindings. Because they were all skinning uphill, the toe pieces were all likely in the walk or lock position, which would have made it very difficult for the skis to release from their feet.

The four survivors, Chris, Nate, Ethan, and Steve, were hoisted off the scene via an air ambulance from Life Flight. With darkness approaching, operations were discontinued until the following day. Before leaving the scene, the two rescuers turned on the victims’ transceivers for the night to ensure they could be found the next day.

The next day, on Sunday, February 7, Unified Police Department (UPD), Salt Lake County Search and Rescue (SAR), Wasatch Backcountry Rescue (WBR), and a helicopter and personnel from the Utah Department of Public Safety (DPS) met at 0700 to resume operations to recover the four victims. DPS transported four personnel from SAR and WBR and their equipment to the scene. There was no safe place to land, and all personnel and equipment were transported to and from the scene via hoist or long line. At approximately 1430, all the victims had been recovered and flown to the incident command post in Millcreek Canyon. Personnel from the Utah Avalanche Center were on scene collecting information about the avalanche and providing assistance in recovery operations.

This was a massive rescue mission involving many different organizations. Chris and Steve saved two lives (Nate and Ethan from group B) with their heroic rescue efforts. Then Chris, Nate, and Steve gave their best attempt to save the rest. Unfortunately, time was working against them. Their rescue efforts were top-notch, and they knew how to perform companion rescue quickly and efficiently. They did the absolute best anyone could do with six full burials.

Photo looking into the trees where the avalanche ran (B. Tremper).

Photo of DPS helicopter removing all the rescuers’ gear at 1430 and leaving the scene on Sunday, February 7.

Terrain Summary

Wilson Glades is a north-facing, 500 vertical foot run in Millcreek Canyon just below the 9,950 foot summit of Wilson Peak which is along the ridgeline separating Big Cottonwood Canyon and Millcreek Canyon. The map below shows an overview of the area, and the X marks the approximate location of the avalanche debris.

Image from the Wasatch Backcountry Skiing map showing Wilson Peak, Wilson Glades, and the location of the avalanche debris (red X).

The avalanche occurred on a northeast facing slope at 9600'. Slope angle where the crown profile was recorded was 31 degrees. Ski tracks from Group A were mostly on the part of the slope where it is 31 degrees. Their uphill skintrack was to the left in the photo where the slope is a touch steeper and then steepens considerably in the trees above. See all the slope angles measured in the photo below. Any slope generally above 30 degrees in steepness is considered avalanche terrain as well as runout zones below. Avalanches generally do not happen on slopes less than 30 degrees in steepness except in rare circumstances.

Photo showing slope angles. Data was collected by Cody Hughes and Clay James.

The route Group B took from Millcreek Road to Alexander Basin Trail to the Wilson Glades is approximately 2,220 vertical feet as you climb mainly along a summer trail and low-angled aspen trees until you reach the glade proper, where it pitches to 30-40 degrees in slope steepness. Just below this increase in slope steepness is where Group B had planned to regroup and discuss their route. At the time of the avalanche they were standing on a 25 degree slope.

Weather Conditions and History

On the day of the accident, the avalanche danger was rated as HIGH for northeast-facing terrain above 9,500 feet and CONSIDERABLE for northeast-facing terrain between 8,000-9,500 feet. The slope on which the fatal avalanche occurred faces northeast at 9,600 feet. The avalanche forecast for the day can be found HERE.

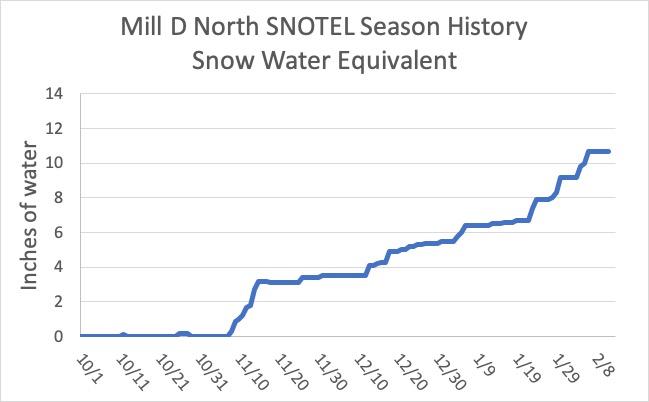

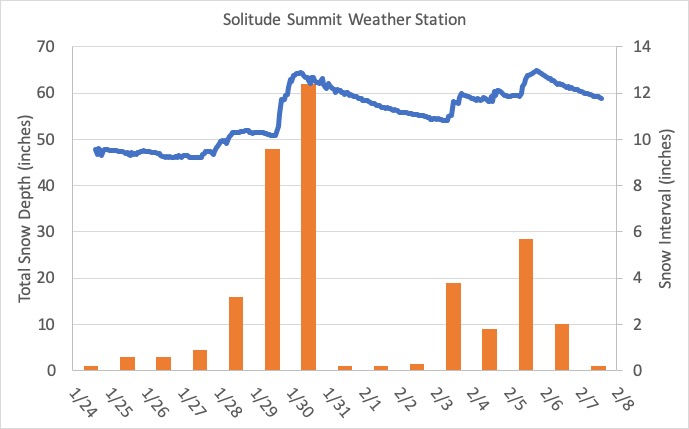

The weak layer for this avalanche was a layer of faceted snow that formed during periods of cold, dry weather in November and December. Two storms the week prior to the accident (February 2/3 and February 5/6) deposited 21" of snow containing 1.8" of water at Solitude Mountain Resort Summit Station, approximately six miles to the southeast of the accident site.

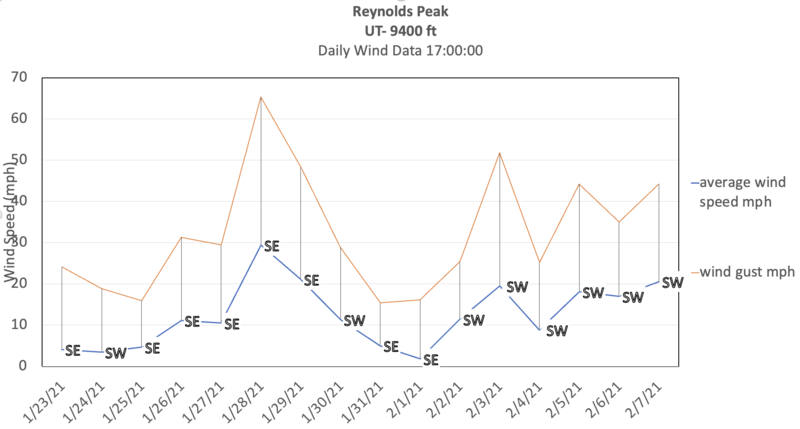

Moderate to occasionally strong winds from the west/southwest for two days prior preceded the accident. At the Reynolds Peak weather station two miles to the southeast at an elevation of 9,400’, wind speeds averaged 15-30 mph with gusts up to 45 mph in the 48-hour period prior to the accident:

Snow Profile Comments

The crown profile revealed the weak layer of faceted snow that caused the avalanche. The weak faceted layer was roughly buried 90 cm / 3 feet deep and 10 cm / 4 inches thick with a 3-6 mm grain size. The hand hardness of this layer was fist hard.

Comments

Photo of the layers in the avalanche crown that are graphed above.

Comments

History of the area and discussion about the terrain

Over the years, the Wilson Glades has been a place of many close calls in part because it is often perceived as safer than nearby terrain to the east (the Wilson Chutes) and the west (northwest chutes into Alexander Basin-February 2010 accident). Being less steep than the nearby terrain, the Wilson Glades seldom avalanches naturally; instead, it seems more often human triggered.

The most recent close call was just a little more than a month ago - Dec 27th, 2020 when a skier unintentionally triggered a soft slab avalanche failing on faceted grains. He reported the avalanche breaking above him but was able to ski off the slab to safety.

Two long-time backcountry skiers shared the following anecdotes about their close calls in the Glades:

- As we approached the ridge, maybe 50' below it, my friend John was in the lead. I saw all these puffs of snow shoot up from around the aspen trees. It was the depth hoar shooting up as the slab collapsed. The whole slope liquefied. Our spot stayed put. Regarding this fatal avalanche, I've never seen the glade slide wall to wall like that.

- I was working as an avalanche forecaster at the Utah Avalanche Center at the time. This was in the early 90's; it was early on in my career on the job. I had taken three other people out there into the starting zone to demonstrate a snowpit. I had taken my skis off and used one of them to cut out a Rutschblock test. As I was sawing the left side of the pitwall with my ski, the entire slope avalanched above me. Luckily I was able to grab a tree and hold on as the wall of snow went by. It was fortunate that all three of the others had their skis on and were miraculously able to ski off the avalanche. This could easily have been a quadruple fatality. A quick search on our website lists 10 reported avalanches since 2010 in the Wilson Glades.

Slope angle discussion

In 2009, Ian McCammon analyzed 496 avalanches to compare avalanche types, weak layers, and slope angles. Read the full article HERE in The Avalanche Review on pages 26-27. He found that 95% of hard slab avalanches happen on slopes 30-45 degrees in steepness.

Bottom line - If a slope is steeper than 30 degrees, it can avalanche.

Aspect and Elevation Discussion

The avalanche occurred on a northeast-facing slope at 9600'. An analysis of all avalanche fatalities in Utah since 1940 showed that most happened on north and northeast facing slopes above 9,500 feet in elevation.

View this short video for a visual representation of all reported avalanche activity in Utah from January 10 to February 8.

Lessons Learned

We aim to learn from accidents like this and in no way intend to point fingers at victims. All of us at the Utah Avalanche Center has had our own close calls and know how easy it is to make mistakes. No one is immune to this. Below are some bullet points as a learning lesson:

- “We were there to have fun, and this isn't fun.” Chris

- Chris, Steve, and Nate performed a heroic companion rescue, trying to save as many people as possible.

- People often try to grab trees but are rarely able to keep their grip. Surprisingly, Chris was able to do so.

- Locked toe pieces keep skis attached to your feet and can contribute to a deeper burial.

- Deeper burials lower the odds of survival.

- Multiple burials lower the odds of survival.

- Former forecaster Evelyn Lees found that 32% of avalanche fatalities of tourers from 2009 to 2017 happened on the ascent. Her study stresses the need to find safe ascent routes.

We are very fortunate to have so many organizations that will help with mountain rescue here in the Wasatch Mountains. Agencies, organizations, and individual involved include the following: Salt Lake County Search and Rescue, Wasatch Backcountry Rescue/Brighton, Solitude, & Alta Ski Patrols, Unified Police Department and Salt Lake County Sheriff’s Office, Utah Department of Public Safety, Life Flight, Cody Hughes and Clay James, Dave Richards from the Alta Avalanche Office.

US Classification of this avalanche is HS-ASu-R4-D2.5-O

Burial locations:

Ethan and Nate: 40°40’37.65” N, 111°40’14.06” W

Sarah: 40°40’37.31”N, 111°40’13.05”W

Louis: 40°40’37.49”N, 111°40’12.90”W

Thomas: 40°40’37.68” N, 111°40’12.82” W

Steph: 40°40’38.83” N, 111°40’13.62” W

The staff of the Utah Avalanche Center's hearts are heavy, and we send our condolences to the family and friends of the victims of this accident.

Right before the helicopter came in to remove the remaining survivors, Chris turned to the group and said, “We all got a second chance at life today; we need to go now make a difference in the world.” The four remaining survivors all hugged one another and left the scene.

Photo of the four people that lost their lives to the Wilson Glade avalanche on February 6th, 2021. Sarah Moughamian (top left), Louis Holian (top right), Thomas Steinbrecher (bottom left), Stephanie Ann Hopkins (bottom right).

Video

Coordinates