Mark Staples

2015-2024 - Director, Forest Service Utah Avalanche Center

This article orginally appeared in BackcountryMagazine.com on February 1, 2019

How quick pits improve decision-making

In another article on BackcountryMagazine.com, Sarah Carpenter described six steps for doing a “quick pit” and answering the question “Am I missing anything?” Make sure to read if you haven’t already. I’d like to offer a few reasons to dig a quick pit, including how it helps our decision making.

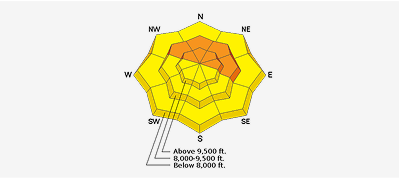

In mid-December I was skiing on Kessler Peak in the Wasatch Mountains. Strong winds had ruined the skiing on many slopes, and we were searching for the few slopes sheltered from the wind. We ascended a ridge and skied the lower part of a run called God’s Lawnmower. It was sheltered from the wind and the powder was five star. After high fives, we figured that one good run deserved another and climbed back up to ski the adjacent run on a different aspect. As we crossed onto the other slope, we were excited to rip skins, then rip powder, that’s it. See you at the bottom.

“Wait!”, my partner said. “Should we dig a quick pit?” Being mid-December, digging was easy because the snowpack was only 2 feet deep. Why not? Can’t hurt. Could help. Maybe a lot.

After 12 light taps on an extended column test, the entire column fractured on a layer of weak, faceted snow. Our perspective changed. Our excitement and stoke to rip powder were tempered by other emotions. We stopped. We looked at a map. We looked at the terrain and adjusted our plan.

I started skiing and once again was absorbed in powder fever. As I descended further, following our plan, a beautiful clearing with a steep slope appeared. Even though we had a plan, it didn’t matter because in that moment, all I saw was a perfect ski line. Without time to think, emotions from digging the quick pit took over, and then I saw a slope that could avalanche. I made a hard turn to avoid the steep slope just as the snow around me collapsed. A crack shot 50 feet in front of my ski tips. There was no avalanche because I turned and stayed off the steep slope. THE QUICK PIT SAVED MY LIFE.

UAC Forecaster Nikki Champion feels layers in the snow. Her perspective has changed being eye-level with the snow engaging different emotions. Photo: M. Staples

Digging a snow pit is a decision making tool.

First of all as Sarah discusses, a quick pit can provide life saving info which is sometimes found under our feet.

Second and just as important, snow pits are a decision making tool. Simply digging a snow pit, regardless of what you find, improves our decision making. This simple, life-saving, 5-minute action can improve communication and harness our emotions in a positive way by changing our perspective. They can also give us valuable rescue practice.

Communication

Before digging our snow pit on Kessler Peak, my partner and I had a simple plan - ski more great powder. After digging, we made a real plan. We decided where to ski. We decided how to watch each other. Most importantly, we talked.

Every day, every group and every slope is different. What this means is that the way we communicate can vary, but our lives depend it. Nearly every person in every avalanche accident says it was a problem. What to do? Dig a snow pit. Standing in the snow pit provides us a moment to STOP and communicate. It gets people talking. I use quick pits all the time, not only because it’s my job, but because I’m tired, need a break, and it gives me a good opportunity to talk with my partners.

Emotion

There are many decision-making traps that most avalanche students learn. By definition they are unavoidable. Having an awareness of them is a good first step, but it does little to help us avoid them.

Solutions include checklists and flow charts which attempt to remove emotion from the decision-making process. This can work great for pilots as when they use a check list before take-off. However, it’s impossible to remove emotion from our decision making. We’re human. When I was getting ready to ski my second run on Kessler, the great powder was tugging my emotions like a tractor beam pulling the Millennium Falcon to the Death Star.

Since we can’t remove emotion, we should find a way to harness it to improve our decision making. Changing our perspective is one way to do this. We can use emotion to improve our decision-making if we change our perspective and bring up other emotions.

Things that bring out strong emotions are: skiing perfect powder, skiing with good friends, seeing weak faceted snow spill out of a snow pit wall, having an extended column jump into our lap, feeling how heavy the snow is when digging a pit, standing with our eyes level with the snow surface, and thinking about people we love.

Digging a quick pit changes our perspective to balance our emotions which improves decision-making. Standing in the snow pit on Kessler Peak gave me a new set of emotions to balance my excitement for skiing. When I reached the decision point at the top of the steep clearing, I turned away from it and lived to ski another day.

Rescue Practice

As an added benefit, digging quick pits help make us more comfortable and competent with our shovel. If not us, don’t we want our partners to be good with their shovel. Personally, I dig hundreds of pits every winter, and each year I relearn the body mechanics that are the most efficient for me. I hope I will never need to use my shoveling skills, but it’s nice to know they are ready.

Quick pits may only take 5 minutes but can save your life. This simple action is an easy way to avoid many decision-making traps (one caveat: As Sarah stresses, don’t use a pit to look for signs of stability). Digging a quick pit will make you smarter because you’ll learn more about yourself and the snow. The quick pit is the best, cheapest, and simplest decision-making tool available.

DIG IT!

Because digging is the hardest part of avalanche rescue, digging a snowpit is a great chance to become proficient with your shovel. Photo: C. Taylor