Drew Hardesty

Forecaster

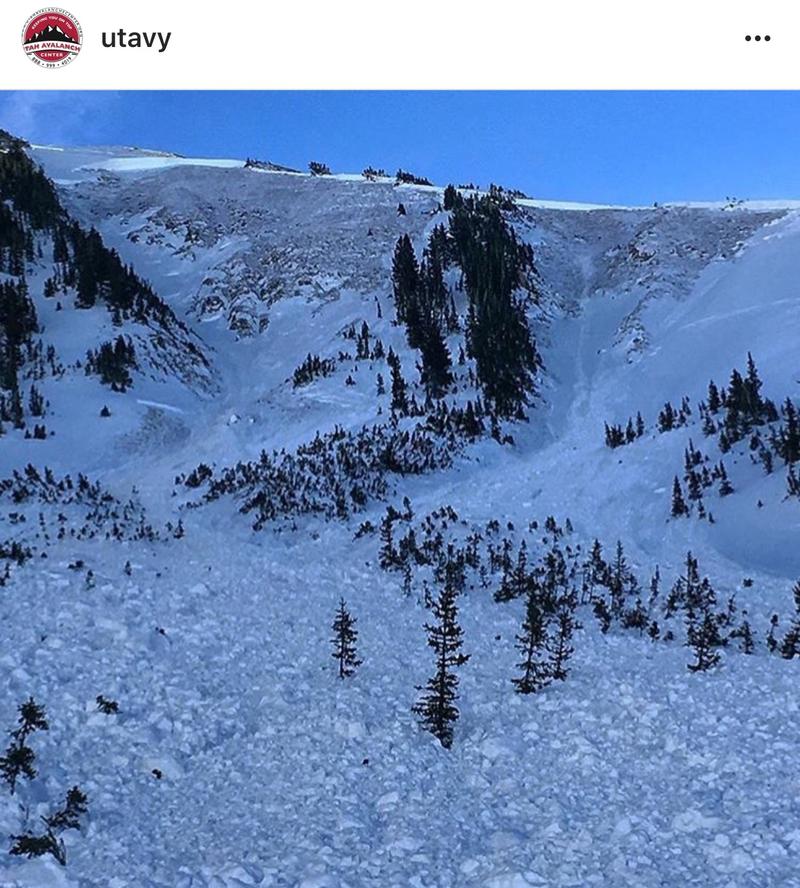

photo: Mark White of a very close call in the Birthday Chutes in Dec 2016.

I thought it would be worthwhile to pull back the curtain again and share some thoughts and struggles of the forecaster in the hot seat.

The old learns as much from the new as the other way around.

This email thread is between me and a new forecaster at another avalanche center.

Limitation of Forecast Guidance

New forecaster -

I'll start with the obvious caveat that it might be more a limitation in my communication and experience and not that of the forecast guidance tools.

It feels there is a missing link in communicating the reality and potential of avalanche danger to the public or maybe that the tools exist but they only make sense to us and are a foreign language to the public. As professionals, we talk so much about uncertainty but we don't have a great standardized way of sharing that with the public when we're using terms such as "likely" "unlikely".

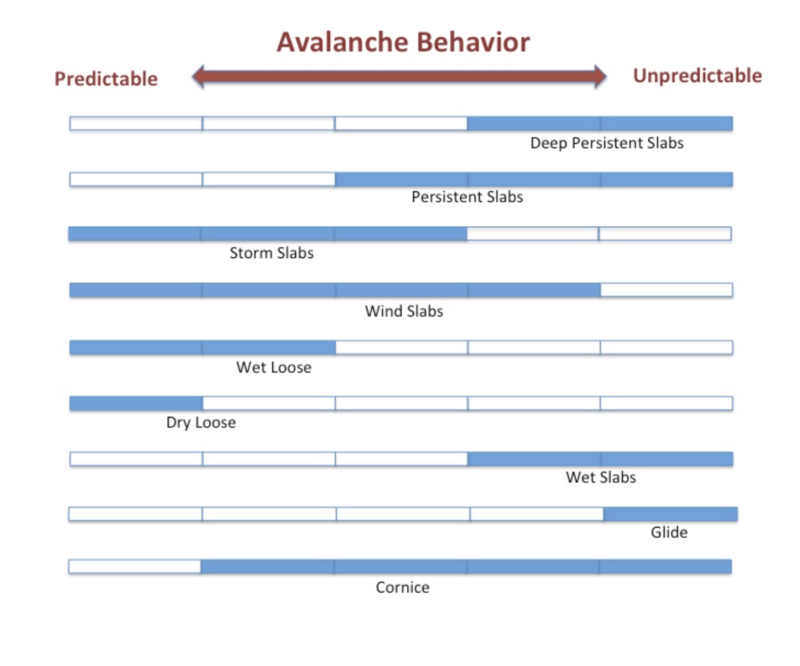

Another missing piece that would be valuable to recreational users to include in a forecast product is the "predictability" of a given avalanche problem. We know that ~70% of avalanche fatalities (in Utah) are caused by persistent weak layers so we should be proactively developing tools to help the public understand the problem better. The "I" buttons on the avalanche problems are a nice feature but I'm not sure it's obvious to the user.

Maybe the bigger issue is that the persistent avalanche problem is counter-intuitive, if you watch 10 people ride a slope it is intuitive to assume it's safe. If you haven't heard about avalanches in several days it's intuitive to assume it is safe. We need to short circuit people's intuition by providing a tool that lets them know their intuition is working against them.

As a recreational user, it would be really beneficial to know how predictable an avalanche problem is as I'm considering all the information I have. how reliable observations are, or if my snow stability tests are reliable? That would be great information to know as I'm making decisions.

Interestingly enough I stumbled upon Heather Thamm's presentation from WYSAW today and found her thoughts to be quite interesting about similar communication ideas.

I started writing this email last week and just finishing it. Since I wrote my original thoughts, I might already be convinced that external influences on the public are a greater contributor to avalanche accidents than any lack of communication on our part.

From Drew Hardesty -

The uncertainty thing. Well good food for thought below - Scott Savage and Ben VandenBos from the Sawtooth Avalanche Center had a nice write-up a couple days ago -

As avalanche forecasters, we spend a lot of time thinking about uncertainty and confidence. Thinking about these things helps us to produce forecasts that are both accurate and useful for you as a reader (at least, that's the idea). On days when we have a lot of information about the snowpack and the weather is simple, we can have high confidence in how the snow will behave. When the weather is changing rapidly and we find ourselves dealing with snowpacks that are unusual, our uncertainty can be high. This is the latter.

There is no reason to hide the fact that we have a lot of unknowns and a lot of unknowables throughout the forecast area. The widespread layer of weak, faceted snow buried in our snowpack is quite unusual, a once in a decade or two sort of thing. The warm, wet weather that we just experienced is also quite unusual for this time of year; Stanley set the record for the highest temperature seen on the solstice, breaking a record that was set over 50 years ago. Now, it's near zero degrees F and there's a little "blower powder" window-dressing on top of the snowpack. The combination of unusual weather and snowpack events basically puts us in uncharted waters. The first step in dealing with uncertainty is to acknowledge its existence.

As our abnormally weak snowpack slowly adjusts to the recent load, remember that weird weather makes weird avalanches. I'll be traveling cautiously today, building some extra safety margin into my program.

There is no reason to hide the fact that we have a lot of unknowns and a lot of unknowables throughout the forecast area. The widespread layer of weak, faceted snow buried in our snowpack is quite unusual, a once in a decade or two sort of thing. The warm, wet weather that we just experienced is also quite unusual for this time of year; Stanley set the record for the highest temperature seen on the solstice, breaking a record that was set over 50 years ago. Now, it's near zero degrees F and there's a little "blower powder" window-dressing on top of the snowpack. The combination of unusual weather and snowpack events basically puts us in uncharted waters. The first step in dealing with uncertainty is to acknowledge its existence.

As our abnormally weak snowpack slowly adjusts to the recent load, remember that weird weather makes weird avalanches. I'll be traveling cautiously today, building some extra safety margin into my program.

--------------

The uncertainty thing is a bit odd I think for a number of reasons. The lay public often want someone decisive (even if they're decisively wrong) and the scientists often get blamed for being too wishy-washy with caveats and, well, humility - we don't know it all. The line Certainty is the Enemy of Wisdom certainly fits here. At the same time, I feel that the public appreciates it (and builds us more trust) when we say, Well, I don't really know how it's going to play out...BUT here's how I would approach the day.

One of the things that sets our world apart is that I argue we can't really develop expert intuition for PWL. We can only know it's there and have a sense of how unpredictable it is. We just don't have that much experience with it and both of these conspire to catch people and professionals alike. How to warn for it?

- Tell stories in your advisory.

- Describe the surprise of seeing old tracks taken out.

- Show the Wolf Creek avalanche video. (above).

- Beyond that, avalanche deaths are pretty esoteric for people, not unlike Covid deaths.

But they're not esoteric for everyone or their family.

Fatal avalanche in the town of Missoula, Montana Feb 2014, The Missoulian

Gobbler's Knob avalanche fatality, January 2016 pc: Hardesty

Wendy Wagner (Chugach NF Avalanche Center) and I felt that our Avalanche Problem Toolbox (example below; infographics by Bruce Tremper and Jim Conway) was a helpful product over and above the danger ratings...as it rated them with tests/observation validity, remote potential; etc and a few other avalanche centers included it in their webpage.

I do like your comments about our lingo being a bit of a foreign language to the recreationists. If I went to the beach and heard dim rumors of rip-tides and saw an orange flag...I wouldn't know what to do. I'd probably play in the baby pool.

All good thoughts. Take your thoughts and run with them. One of my favorite parts of our job is to have these conversations.

From the new forecaster -

I continue to think about this and I think ultimately I want people to have a better understanding of the risks they take. I trust people to make wise calculations if they really do understand the risk vs. reward. I don't like being the guy who looks at tracks and says "what the heck was that person thinking?" but from what I've seen people do, it makes me believe that they don't understand the reality of the risk they're taking or just how unpredictable, trick, and long-lasting the Persistent Slab problem is. Maybe they do and their calculation of risk is just far different than mine. As I've heard you say before, and I agree; the level of acceptable risk is very unique for each person and it's our job to provide them the information, what they do with that information is up to them.

I think the tools we use to convey that risk are helpful to specific people and the truly-educated backcountry user but "educated backcountry user" is a self-proclamation and I don't think skiers, snowboarders, or snowmobilers who have taken a Level 1 and think they are now educated walk away having a complete grasp of the level of risk they assume getting onto steep slopes.

I believe there are many backcountry users who are like me, in that when I started taking avalanche courses I was seeking out that silver bullet, the definitive information I could gather to know when I could ski steep, deep powder.

It wasn't until a few years in that I realized that silver bullet didn't exist, it was all a calculation of risk.

Input: How likely is the avalanche to happen? How big will it be? What will happen if I am caught? How certain am I of those variables? The forecast products do a good job of telling people how big it will be and how likely it is to trigger, but until people understand the specific criteria for the language we use to communicate I don't think they will fully understand the risk. It's not all on the users.

This is where I see improvement needed from our side too. The language used either needs to be clear, common, easily understood language, or the definitions and criteria need to be front and center beside the products.

Your example of showing up at the beach is spot on, I suppose that's the challenge of making public safety products useful enough for the most likely users and simple enough for the layperson.

As always, thanks for entertaining the conversation. I appreciate your thoughts.

Video - The Seventh Skier

Robert Crowe footage from near Wolf Creek in the San Juans of Colorado.

Robert Crowe footage from near Wolf Creek in the San Juans of Colorado.

Current avy speak has left me, unfortunately, out in the cold. More than 50 years of successful multi-day/multi-week backcountry experience here and, yes, caught in slides going back to the early 70’s. Learned deep lessons from that. Suggest you encourage plain speaking. That’s all.

Daniel Hindert (not verified)

Wed, 1/6/2021

Super Awesome dialogue, and a cool concept on digging into the underlying calculations and ideas people have about forecasts, snow pack, and terrain. I think there is some grist to be chewed on, when speaking of intuition (good) versus assumptions (danger!). Ultimately, it's a noisy era in humanity, media, ego, competition, population. Good decision making comes from listening, considering information, observing signs, careful analysis. And it's never a bad decision to be conservative. There are more people than ever storming the backcountry... Almost hard to witness at times, in my short span of 25 years in the western mountains. I am super thankful for all the forecasters and organizations who continue to bring forward these great tools and information, always evolving, and hosting fantastic dialogue. All the best, dj

derek jones (not verified)

Thu, 1/7/2021

Excellent! Another great effort to emphasize how unpredictable the snow can be and that each foray into the backcountry is our decision to poke the bear.

Jonathan A Webber (not verified)

Thu, 1/7/2021