Observer Name

UAC staff

Observation Date

Monday, February 22, 2021

Avalanche Date

Saturday, February 20, 2021

Region

SE Idaho » Bear Lake Area » Sherman Peak

Location Name or Route

Sherman Peak

Elevation

9,400'

Aspect

East

Slope Angle

37°

Trigger

Snowmobiler

Trigger: additional info

Remotely Triggered

Avalanche Type

Hard Slab

Avalanche Problem

Persistent Weak Layer

Weak Layer

Facets

Depth

3.5'

Width

450'

Vertical

1,000'

Caught

1

Carried

1

Buried - Fully

1

Killed

1

Accident and Rescue Summary

48-year-old Allen Foss of Preston Idaho was killed by an avalanche Saturday, February 20, 2021 while riding in the backcountry near Sherman Peak, northwest of Montpelier, ID. Our condolences go out to the friends and family of the victim and those involved in the rescue.

Three snowmobile riders left the Copenhagen Basin parking area in Emigration Canyon Saturday morning, February 20, 2021. The party rode towards Sherman Peak, about 10 miles to the north. The group mostly stayed in the trees and avoided open slopes and gullies during their ride.

At around 10:30, the party approached the east side of Sherman Peak from the south. Rider 1 climbed across the lower shoulder of the east facing slope but stopped short of a deep gully. Rider 2 rode in below him and stopped as well, before the gully. Allen came in below the other two riders and, unable to hear verbal warnings from Rider 2 to stop, continued into the gully where he was last seen.

Rider 2 saw the avalanche a second before it hit, yelled “AVALANCHE”, wrapped his arm through his handlebars, and braced for impact. He was blasted hard by the airborne powder cloud, and a deep torrent of heavy avalanche debris ran about 6 inches in front of his sled’s skis. Rider 1 was stopped on the edge of the gully uphill a little bit from his father and tucked below a small knob that seemed to have deflected the flow a little. He did not see the avalanche until the powder cloud came out of the clouds. He thought it was just blowing snow until he saw chunks of snow flying 30 feet in the air. He was also hit by the powder cloud and was around 6 feet from the avalanche flow.

After the avalanche debris stopped, both Allen and his sled were gone, and it did not take long for his companions to realize that the avalanche had buried him. The avalanche likely hit Allen from behind and knocked him off his snowmobile in the gully. He was later found under about 12 feet of heavy avalanche debris in an upright, seated position, a few feet uphill of his sled which was buried, flipped on its side, nose facing downslope.

Allen was not wearing a beacon at the time of the accident, although his companions thought he was. They believe it might have fallen out of his pocket earlier that morning. Riders 1 and 2 both carried beacons and each had shovels and probes attached to the tunnels of their sleds. The two riders searched the debris with beacons for approximately 40 minutes with no success. Rider 2 returned to his snowmobile and went down the lower part of the gully towards the road to look for tracks out of the debris and to get help.

At around 11:00 am on February 20, 2021, the Bear Lake County Sheriff's Office was notified of the avalanche accident. Search and Rescue units from Bear Lake County, Caribou County, and Franklin County responded to the area.

Mike Porter of Preston owns a cabin at the base of Skinner Canyon, and on the weekend of the accident was hosting and instructing a private avalanche class with about 20 people, including friends and family, mostly teens and young adults. The class was en route to the Sherman Peak area to practice companion rescue, and a few of the young snow bike riders were nearly to the avalanche site when Rider 2 came downhill, requesting help. It took a few minutes for the students to realize that this was not a drill. There was a huge pile of fresh avalanche debris, this was real! One student contacted Mike Porter on the hand-held radio. The rest of the class was summoned, and they made their way up to the avalanche site.

Porter’s avalanche class and Riders 1 and 2 continued to use beacons to search the debris. After some time, the rescuers realized that either Allen’s transceiver was not transmitting or he wasn’t carrying it. Porter organized his students into a probe line, starting at the last seen point, where Allen’s sled tracks led into the deep debris pile in the gully, working downhill. The heavy avalanche debris in the gully was deep, and in some areas, the rescuers could not hit the ground with 10’ probes. One of the rescuers struck the tunnel of Allen’s snowmobile 9'10" deep with his 10' probe. Members of the rescue party excavated the deeply buried sled, while others continued a grid search with probes.

When the first members of the Bear Lake County Sheriff's volunteer Search and Rescue team arrived at the accident site, about 45 minutes after the report, Porter’s avalanche students had already found and partially dug out the snowmobile. Rescuers continued to dig out the snowmobile, while others continued to search with probes.

Allen was struck with a probe from within the snowmobile excavation hole, a few feet uphill and a little below the level of the snowmobile. The rescuers could not hit him with a 10-foot probe from the surface of the debris, because he was buried too deeply. By this time there were over 30 rescuers at the accident site. They spent approximately 30 more minutes digging him out of the avalanche debris. There happened to be a doctor in Porter’s class who was able to determine that, despite the heroic rescue attempt, Allen had passed.

Terrain Summary

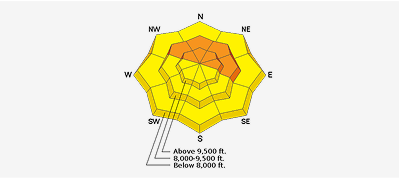

The accident occurred on the east side of Sherman Peak (9,682') in the northern Bear River Range. The avalanche is rated HS-ASm (r)-D3-R3-O. The avalanche on an east-southeast facing slope involved most of the winter’s snowpack. It was about three-and-a-half feet deep and we estimate 450 feet wide. It started at around 9400’ in elevation and descended about 1000 vertical feet.

The victim was buried around 12 deep in the gully, at about 8700 feet in elevation, approximately 40 feet downhill of his tracks entering the avalanche and his last seen location. He was found in a seated position uphill a few feet and a little below the level of his snowmobile, which was flipped on its side, skis pointing downhill.

Weather Conditions and History

Much like the rest of the Intermountain west, the Northern Bear River Range experienced low snowfall well into January 2021. Prolonged periods of high pressure without storms created a persistent weak layer of sugary faceted snow. Just over a week before the accident, the Emigrant SNOTEL site received more than 4 inches of Snow Water Equivalent. Snow depth rose from about 40 inches to near 60 inches with much of that snow falling earlier in the period, on February 12.

Winds during the week prior to the accident were generally moderate, although from February 16 through February 18 westerly winds blowing 10-20 mph with 30 mph gusts were recorded. Combined with the newly fallen snow, the winds created large slabs of wind drifted snow on leeward slopes. The day of the accident the sky was overcast with light snowfall and light winds. Visibility was limited due to low clouds and snow showers.

Snow Profile Comments

The snow profile displayed about a 3.5' slab of wind drifted snow resting on top of weak faceted snow. The avalanche failed just under a very thin rime crust at the bottom of the slab.

Comments

On 2-22-2021, Paige Pagnucco and Toby Weed visited the accident site with several of the rescuers...

Comments

All of the fatal avalanche accidents we investigate are tragic events. We do our best to describe each one to help both the people involved and the community as a whole to better understand them. We offer these comments in the hope that it will help people avoid future avalanche accidents. We do not intend to place blame on any of the involved parties or imply that any particular action or decision would have prevented this tragic event.

Consequences: Allen was very deeply buried in a gully, or a terrain trap. He was buried under about 12 feet avalanche debris. Survival of such a deep burial is extremely rare.

According to Auger and Jamesen, (1996 ISSW), close to 90% of those recovered alive in the US database and 95% of those recovered alive using Swiss statistics “were found at depths less than 1.5 m ” (close to 5 feet).

Comments

Rescue gear: Allen was buried without a transceiver. It is extremely unlikely that he would have survived the very deep burial with a transceiver, but the recovery time would probably have been reduced if he had been wearing one. His companions thought he had an avalanche transceiver with him and believe it may have fallen out of his pocket that morning.

Identifying Avalanche Terrain: All users are encouraged to attend an avalanche awareness class or more advanced training to learn safe travel techniques. Avalanche conditions across the intermountain west are especially dangerous and treacherous this winter, because of a widespread deeply buried weak layer of sugary or faceted snow. Avalanches failing on a persistent weak layer can be triggered by people remotely, or from a distance. In fact, the Utah Avalanche Center in Logan received several reports of large remotely triggered avalanches in the area during the weeks preceding the accident including one that occurred that day on Wilderness Peak, also in the northern Bear River Range.

Rider 2 said it well, “The only way we could have avoided this avalanche accident was for us simply to not have been there.” The avalanche occurred several miles north of the Logan Forecast Zone, and the party did not regularly access the avalanche forecast before heading out into the backcountry. They did not read the forecast on the morning of 2-20-2021, (https://utahavalanchecenter.org/forecast/logan/2/20/2021), but the danger was rated as CONSIDERABLE and recommended that people, “Choose safe routes in low angled terrain well out from under and not connected to drifted slopes steeper than about 30 degrees.” And, in the description of the buried persistent weak layer problem, “Avalanches failing on a buried persistent weak layer might be triggered remotely, from a distance, or worse from below!”

Coordinates