Observer Name

Trenbeath, Staples

Observation Date

Saturday, January 26, 2019

Avalanche Date

Friday, January 25, 2019

Region

Moab » Dark Canyon » East Face Laurel Peak

Location Name or Route

Dark Canyon

Elevation

12,200'

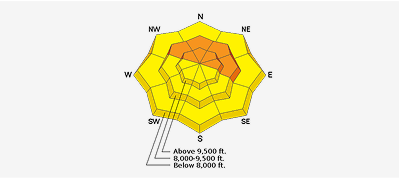

Aspect

East

Slope Angle

35°

Trigger

Snowmobiler

Trigger: additional info

Unintentionally Triggered

Avalanche Type

Hard Slab

Avalanche Problem

Persistent Weak Layer

Weak Layer

Facets

Depth

4'

Width

900'

Vertical

1,500'

Caught

1

Carried

1

Buried - Fully

1

Killed

1

Accident and Rescue Summary

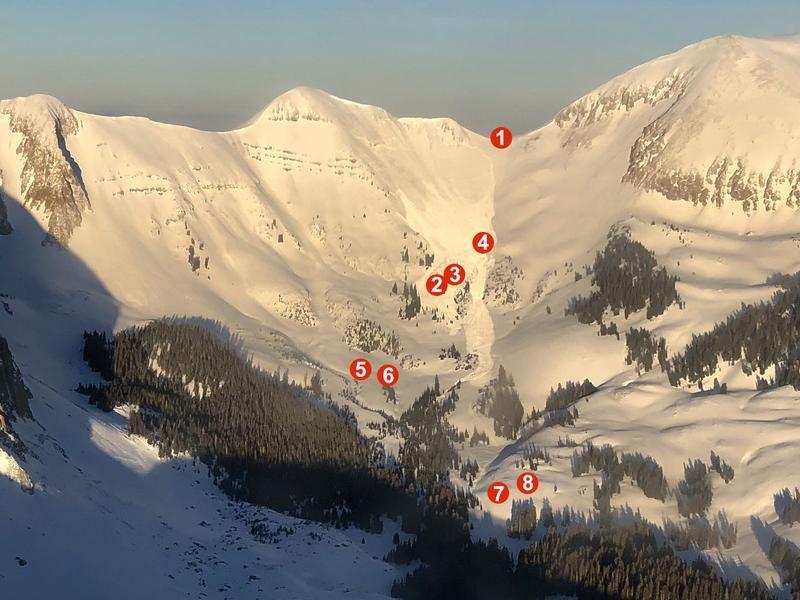

On January 25, 2019 a party of six snowmobilers and two snowbikers from Monticello, Utah were riding in Dark Canyon, in the La Sal Mountains of southeastern Utah. At approximately 4:00 p.m. one member of the party (rider 1) climbed to a steep, high pass with an easterly aspect at 11,974’, between Mount Mellenthin and a sub peak of Laurel Mountain. Three other members of the party followed with riders 2, 3 veering off to the looker's left, while rider 4 took a straight line up a narrow gully. Two snowbikers (riders 5, 6) were lower to the left, under a group of trees beneath the SE face of Laurel Mountain. Riders 7, 8 were riding beneath a small knoll out of sight of the rest of the group.

Rider 1 reported feeling a collapse as he looked down from the pass, and he saw the slab fail and propagate outward onto the entire NE face of adjacent Laurel Mountain. Rider 4, who was headed up the gully, took the force of the avalanche head on from approximately 600' below where the slide had initiated. Riders 2, 3 reported last seeing him in the avalanche at approximately 11,350’. Riders 2, 3 rode out to safety on the looker’s left side.

When the avalanche stopped, the party regrouped near the toe of the debris, did a head count, and realized that rider 4 was missing. Members of the party attempted a search. Between them they had 3 beacons, two shovels, and one probe. They believed rider 4 was wearing a beacon, and reported hearing a “ping.” They uncovered a snowmobile near the toe of the debris, and located a helmet, but not the victim. Rider 5 left the scene to call 911, and San Juan County dispatched a Classic Air Medical helicopter, but as darkness was falling, further search and rescue efforts were suspended until the following morning.

Photo illustrates the position of party members at the time of the avalanche. Rider numbers listed in the text above are labeled in the photo.

Coordination efforts between San Juan and Grand counties, and the USFS Utah Avalanche Center began around 6:00 p.m. with the San Juan County Sheriff’s Office in command. Plans for search and rescue efforts the following day included an aerial reconnaissance to determine scene safety, and contingency plans for avalanche mitigation, and professional avalanche rescue dogs and handlers from Wasatch Backcountry Rescue, with support from the Utah Department of Public Safety.

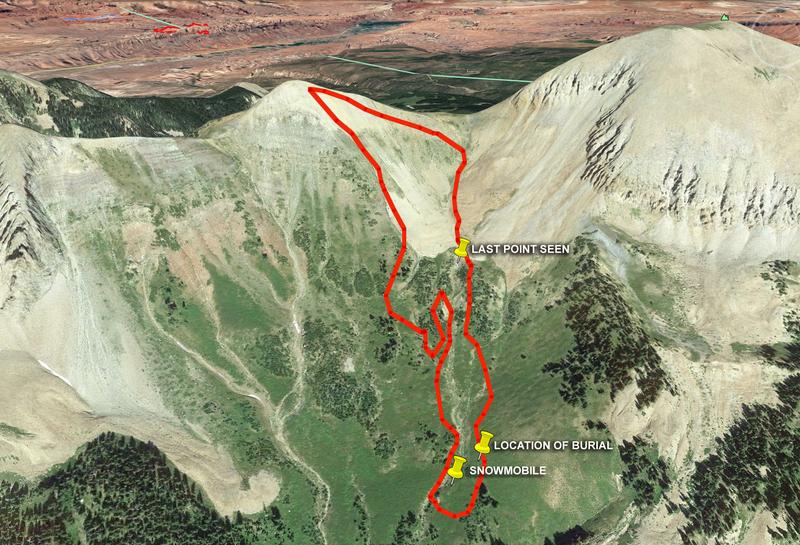

At 7:00 a.m. on January 26, a reconnaissance flight determined that avalanche mitigation work would be required to render the scene safe for search operations. While waiting for the arrival of the bombardier team, a DPS helicopter flew over the debris with a RECCO unit and a Long Range Receiver (LRR). A RECCO unit is a specialized search device for people with a RECCO reflecting chip built into their clothing. The LRR detects signals from avalanche beacons. They reported a signal from the LRR near the last point scene and dropped a flag. Avalanche mitigation work produced one very large avalanche but the debris did not over run the original avalanche debris. This work was completed at 2:35 p.m. and dog teams were inserted near the last point scene at 3:10 p.m. A beacon search was performed with one of four searchers receiving an erratic signal. A dog alert near the signal prompted a probe search of the area. Meanwhile, the other dog and handler continued down the debris. At 4:20 p.m. the second dog alerted near the toe of the debris, and at 4:35 a positive probe strike was made. The body was recovered about 150 feet uphill of the victim’s snowmobile. He was buried 2-3 feet deep. He was not wearing a beacon, but had one turned off in his pack.

Burial location: 38.45451 -109.22817, Elevation 10,920

Victim’s snowmobile: 38.45402 -109.22805, Elevation 10,840

Toe of debris: 38.45383 -109.22775, Elevation 10,830

Google image illustrates the locations of the point last seen point, the victim's snowmobile, and final burial point.

Photo illustrates site of victim's burial with pack for scale.

Terrain Summary

Located on the east side of the La Sal Mountains, upper Dark Canyon is a high alpine cirque surrounded by the prominent peaks of mounts Mellenthin, Laurel, and Peale. The area is remote and generally visited only by snowmobilers. Like most alpine areas in the La Sals, upper Dark Canyon is comprised of steep, open, avalanche terrain, punctuated with cliff bands and steep convexities. The slope that avalanched extended from a southeast facing saddle below the southwest ridge of Mount Mellenthin, up to the summit of northeast facing Laurel Mountain.

Weather Conditions and History

Season Synopsis

Early October storms brought 2’-3’ of snow to the La Sal Mountains above 10,000’. Snow remained into winter on E-N-NW aspects. A melt freeze crust of varying thickness developed with facets underneath. At lower elevations, melt freeze snow, or moistened and refrozen facets made up the entire base layer.

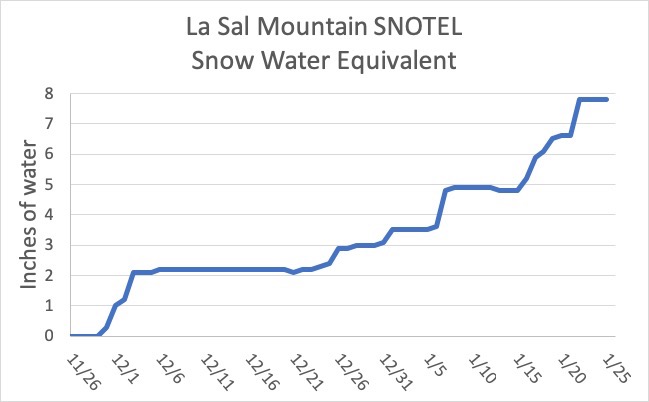

Conditions then remained dry until two storms between November 30, and December 2, brought up to 30” of snow. Most of December was dry, and the snow settled and faceted to the point that it was possible to trigger loose avalanches down to the October melt freeze crust later in the month.

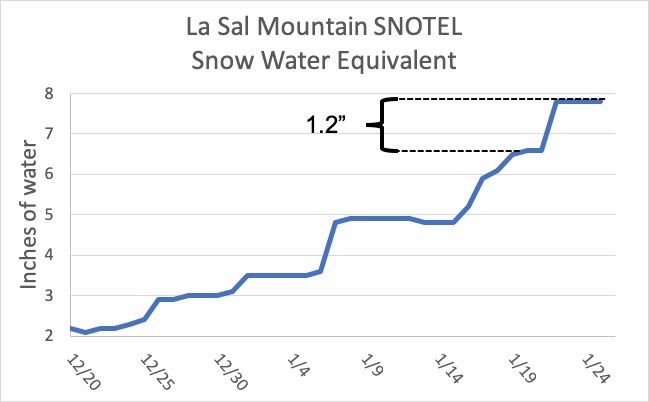

Over Christmas, 6-8” of snow fell accompanied by moderate to strong SW winds. Natural avalanche activity occurred during this period, both as loose snow sluffs, and as wind slabs failing on the faceted interface above the October crust. This kicked off an active weather pattern with regular storms, and a cumulative Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) over the next 30 days totaling 5.7”. Avalanche conditions throughout the period were very sensitive with widespread collapsing, shooting cracks, and frequent natural avalanches. Two Avalanche Warnings were issued, and a major cycle occurred on January 18. Natural avalanches also occurred on January 16, 21, and 24.

Snowpack

The snowpack can be broken down into three major events – October snow at the base of the pack, early December snow as a faceted weak layer, and storms since December 26, forming a cohesive slab 3’-4’ deep on top.

Weather history the week of the accident

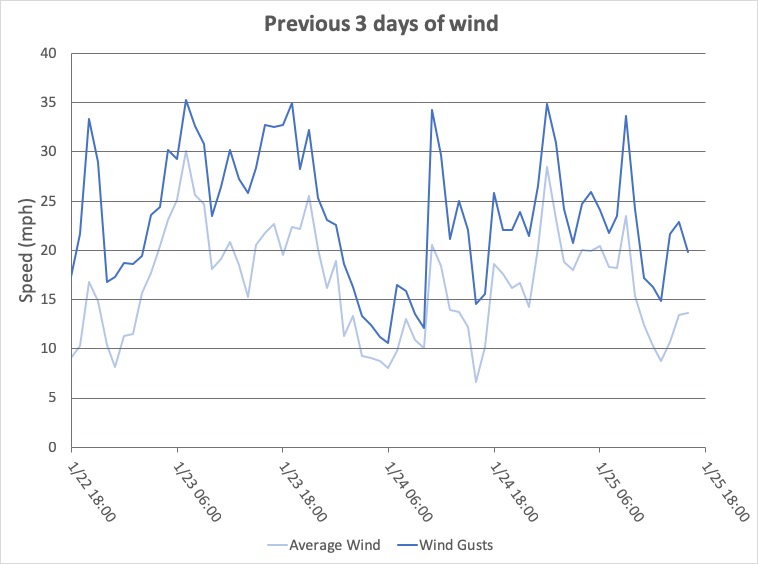

By Wednesday, January 18, three-day storm totals equaled 18” of snow at 1.75” SWE. This produced a wide spread natural cycle on E-N-W aspects. On January 20-21, 14” of snow fell with 1.2” of SWE producing more natural avalanche activity. January 21-25 brought on a windy period with moderate to strong west to northwest winds

Season snowfall in Snow Water Equivalent (SWE)

SWE for past 34 days leading up to the accident.

Winds for past three days leading up to the accident.

Snow Profile Comments

Due to the magnitude of the slide, inaccessibility of the crown, and circumstances surrounding scene safety and the timing of the search, it wasn't possible to do a snow profile. It is believed that like most other avalanches that have occurred since December 26, that this avalanche failed on a persistent weak layer of faceted snow that formed in early December. Wind drifts deposited over a period of days prior to the accident likely contributed to the instability.

Comments

The La Sal Mountain avalanche forecast for the day rated the danger as Considerable, with human triggered avalanches involving wind drifted snow, and buried persistent weak layers likely on steep slopes facing NW-N-E, on mid and upper elevation terrain. Travel advice recommended sticking to wind sheltered, low angle terrain and meadows.

We aim to learn from accidents like this and in no way intend to point fingers at victims. All of us at the Utah Avalanche Center have had our own close calls and know how easy it is to make mistakes including forgetting to turn on our avalanche beacon.

Please carry appropriate rescue gear - beacon, shovel, probe, and know how to use it.

Check the avalanche forecast and choose terrain appropriate for conditions.

Keep track of your partners, and only expose one person to danger at a time.

We would like to thank all of those involved in the search and recovery effort including San Juan and Grand County Search and Rescues, Classic Air Medical and the Utah Department of Public Safety, Snowbird, Wasatch Powder Bird Guides, and professional dog teams from Wasatch Backcountry Rescue, Alta, and Park City ski patrols.

Coordinates