Forecast for the Salt Lake Area Mountains

Issued by Drew Hardesty on

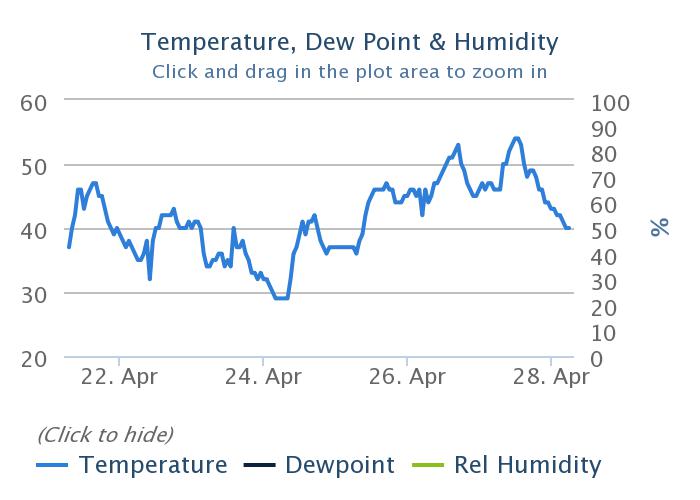

Tuesday morning, April 28, 2020

Tuesday morning, April 28, 2020

Regular avalanche forecasts with avalanche danger ratings have ended. We will continue to post all observations so please keep submitting them as you get out in the mountains. We will issue updates with any new snow that falls through the end of April.

During the spring we typically deal with three different avalanche problems:

1. Wet snow: Get out early and get home early. Get off of--and out from underneath--any slope approaching 35 degrees or steeper when the snow becomes wet enough to not support your weight.

2. New snow: We almost always get several winter-like snow storms in April and May. Treat each storm just like you would in winter. Avalanches can occur within the new snow typically from 1) low density layers deposited during the storm, 2) high precipitation intensity during a storm and 3) when cold, dry snow becomes wet for the first time, it almost always means wet sluffs (loose snow that fans outward as it descends). This can happen within minutes of direct sun on cold snow.

3. Wind Drifted Snow: Wind can rapidly load snow onto steep slopes making those slopes more prone to avalanching. Wind drifted snow looks rounded and pillowy, in some cases it can sound hollow like a drum. Be sure to check upper elevation wind sites in the links below to get an idea of what the winds have been up to.

Lastly - Glide Avalanches. These are an isolated issue and usually occur in areas where the snow rest on smooth rock slabs. The release of a glide avalanche is unpredictable, but it is usually preceded by the opening of a visible glide crack. The main way to avoid these slides is simply avoid being under slopes with a large glide crack.

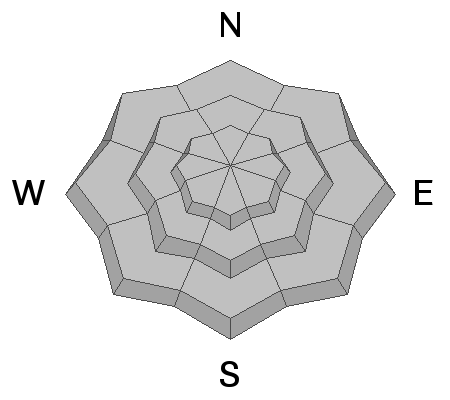

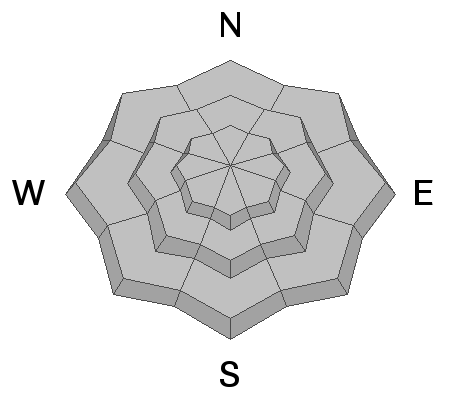

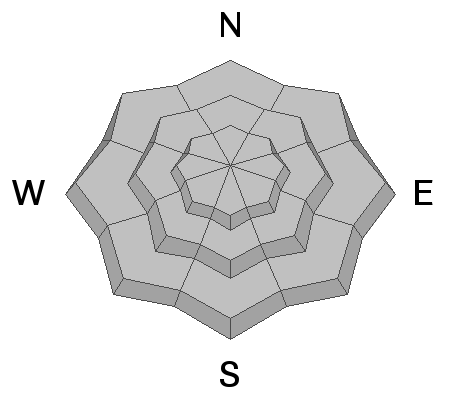

Low

Moderate

Considerable

High

Extreme

Learn how to read the forecast here