Eric Trenbeath

Forecaster

At the 12th annual USAW (Utah Snow and Avalanche Workshop) I gave a presentation on the epic avalanche conditions we experienced in the La Sal Mountains last winter. It all started with early-season October snow, followed by an extended period of high pressure, just like many mountainous areas in the Intermountain West are experiencing right now. We are currently high and dry in the La Sals, but for those of you who live in areas with snow, pay close attention to where it is and how weak it becomes. And then, even more importantly, pay attention to how it reacts when new snow is finally added.

MOAB – the Mother Of All Basal Weak Layers

A season of trepidation and destruction in Utah’s La Sal Mountains

By Eric Trenbeath

basal (rhymes with basil): forming or belonging to a bottom layer or base.

It happens every hundred years or so. A combination of weather factors over the course of winter create a prolonged period of dangerous avalanche conditions that challenge human perspective and reconfigure the landscape. The winter of 2018/19 was just such a winter in the La Sal Mountains of southeastern Utah. A particularly persistent weak layer, and a snowfall of more than 200% of average, created a season of sketchy, hair-trigger avalanche conditions that resulted in a fatality, numerous natural cycles, and a historic event in mid- March, that wiped out mature aspen stands, and 75-100-year old Douglas Firs in the process.

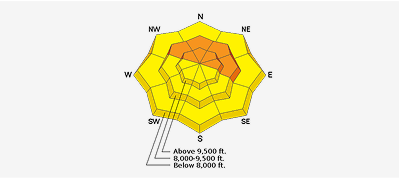

The season started early. Between October 5 - 7, 2018, a series of moist and powerful storm systems brought heavy rain and severe flash flooding to the Four Corners region of the Desert Southwest. When the gray, heavy, moisture-laden clouds finally broke, and the cold air moved on to the east, the peaks of the La Sal Mountains appeared pasty white, plastered with more than 3’ of snow above 10,000’. With winter trailhead access plowed to 9600’, and peaks approaching 13,000’, this made for a lot of early-season snow in the prime recreation zone.

Local skiers and even some out of towners flocked to the mountains for what was likely the earliest legitimate turns in La Sal history. The following week, scattered storms put down another foot of snow and then the hose turned off. As is typical for late fall in the region, high pressure moved in. Unfortunately, it hung around for a long and extended period. A few hopeful looking November storms passed by to the north before dipping down into Colorado, leaving our isolated desert range high and dry. And the once-promising 3’-4’ of October snow deteriorated into an ice/facet conglomeration that remained on the ground for the rest of the season, even on many of the highest, southerly aspects.

It started snowing again on November 30, more than six weeks after the early October snows. Four days of storm brought another 30” to the mountains and we thought it was finally going to be game on. But the storm track again moved to the north, and by late December, the snow that fell early in the month had metamorphosed into a sugary, faceted layer that was as loose as dry sand, and it began to sluff off the surface of the October snow, creating the perfect weak layer/bed surface combination for the epic winter that was to come.

And then it came. Starting the day after Christmas, and continuing through March, storm after storm cycled through, each one producing natural avalanches that grew continually larger and more widespread as the weak layer was buried deeper, and the overriding slab began to connect more areas of terrain. By mid-January, backcountry travel in the La Sals was akin to traveling through an over-deployed minefield, with human triggered avalanches all but certain. Collapsing and whumphing in the snowpack were rampant, and stiff wind slabs stretched taught as a drum over the underlying, early December weak layer.

Conditions were the most sensitive I had seen in more than 30 years of winter backcountry travel. Local observers and the backcountry community were fit to be tied. It was finally snowing and the range of available ski terrain was reduced to low angle wooded areas, and open slopes less steep than 30 degrees, both of which are in short supply in the La Sals.

Then, on the morning of January 25, a party of eight snowmobilers from Monticello, Utah headed around to the east side of the range and ventured up into the high alpine basin of Dark Canyon. It had been snowing all week, but the details and severity of the avalanche danger were unknown to the group and they were anticipating a day of excellent powder riding. On the way to Dark Canyon, the party did indeed enjoy incredible snow conditions as attested by helmet cam footage recovered from that fateful day. Around 4:00 p.m. the group arrived at the base of a high alpine cirque. Like most of the alpine terrain in the La Sals, there was no middle ground. It was either go big or go home. One rider made the decision to go big, and he shot up a steep gully flanked by a northeast aspect on one side, and a southeast-facing slope on the other. By navigating the southeast aspect, he was able to achieve a high saddle near 12,000’. Three other riders attacked the slope with one heading straight up the gully. The rider at the saddle reported hearing a collapse and said that suddenly, “the whole mountain just came down.”

Between January 15 and 21, 32” of snow at 3” of Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) had been added to the fragile snowpack. Since the day after Christmas, more than 6” of water, and several feet of snow had fallen prompting natural avalanche activity on January 16, 21, and 24, with a major cycle occurring on January 18. I had issued two avalanche warnings and rated the danger as considerable or high throughout the period. Between January 21, and 24, moderate to strong northwest winds picked up, and the high country was covered in wind slabs.

The avalanche measured almost 1000’ wide and ran for over 1500’ vertical feet. The average depth of the fracture was 4’. Remarkably, two riders in the path managed to turn and get off the slope. The rider shooting straight up the gully was hit head on. The debris was forced through a narrow gulch where it piled up to more than 20’ deep, while over wash continued on down the slope for another 1000’. The party assembled and began a frantic search in the fading light but were unsuccessful in locating the victim. A major recovery effort was launched the following day. The body of the rider was recovered near the tow of the debris. He was buried 2’-3’ deep. He had a beacon turned off in his pack.

As we moved into February, the snowpack began to quiet down and we tried to convince ourselves that we were rounding the bend toward greater stability. Snowpits dug by myself, and local observers, revealed many areas where the snowpack was gaining strength, while the weak layer was still alive and well in others. And though not nearly as frequent or widespread, the bombs would still go off. You’d be skinning along, not seeing any outward signs of instability, and then all of a sudden you would hear and feel a “whumph!” and your hair would stand on end as you collapsed an acre field of snow around you. Then, on February 19, a party of snowmobilers traveling along a forested ridgeline remotely triggered an avalanche several hundred feet wide that broke into a steep, northeast facing bowl. Exasperating our concerns was the fact that high elevation, south facing terrain had a reactive persistent weak layer as well. We were still a long way from being out of the woods.

March roared in like a lion, with strong southwest winds and another two feet of snow in the first week. Then, over a period of 36 hours between March 12-14, the mountains received 32” of snow at 3.6” SWE. This proved to be the final straw. The basal weak layer that had plagued us for the entire season was wiped away as the entire season’s snowpack broke loose to the ground.

The full extent of the avalanche cycle wasn’t completely revealed until Forest Service trail crews began to work their way around the range where they discovered drainage after drainage filled with downed timber. Up until then, an avalanche off the west face of Mount Tukuhnikivatz, with its flattened mature aspen stand visible from the town of Moab, was the only indicator of something truly historic. To be sure, we saw plenty of other carnage right after the event. A northeast-facing slide path I’ve come to call “Old Reliable” released up to 12’ deep and more than half a mile wide. Virtually every north face had run big, even though many were repeaters by this point, but the greatest devastation came from infrequently running, south through west-facing slopes.

And then, just like that, it was over. A winter of trepidation and destruction gave way to a deep and stable snowpack. After being tested by such a severe load, any path that hadn’t run had proven itself strong enough to stay in place. And a long slow, and cool transition into spring, punctuated with continued smaller doses of snow, likely contributed to further strengthening of the snowpack, preventing what could have been a major wet slab cycle failing on the deeply buried, persistent weak layer.

Lines opened up that hadn’t been skiable for more than 25 years, and people were skiing them. It was hard to believe that an area that had been so dangerous, for so long, could turn into such a playground. But that’s the mountains. The key is in knowing when you can go. And when you have the Mother Of All Basal weak layers, you may have to wait for a long time.

Hi Eric,

Great presentation and thanks for sharing your wealth of knowledge. At what point do you start feeling a little more at ease when you have such a questionable snow pack? How much trust do you put into snow pits as the season goes along and what observations do you put more value in? The Uintas typically get the early season snow which facets and lingers for a chunk of the winter. Thanks for your time.

Ted Scroggin (not verified)

Tue, 11/12/2019

Hi Ted, thanks for your question. I know you often have a similar snowpack and I follow all the good work you do up there. In the case of last season, we really couldn't trust it until after the mid-March avalanche cycle. 3" of water in 36 hours pretty much brought the whole house down, and I felt that any slope that hadn't run at that point had been sufficiently tested and was capable of withstanding any future load. Otherwise, I don't think I would have ever been at ease with it. I put a lot of value on snowpits, particularly ECT tests until the weak layer is buried by more than about 4' of snow. Then I rely on how the snowpack reacts to each new load, and how much time has elapsed since the last avalanche event, along with looking for the usual signs of instability. Last season, the snowpack was very audible with widespread collapsing and whumphing for almost two months. As it decreased, I tried to get more comfortable with things but isolated, large collapses would still occur so it was obvious that we weren't out of the woods. Bottom line, the old adage of never trust a depth hoar snowpack typically prevails.

Eric

Thu, 11/14/2019