The Utah Avalanche Center is the interface between avalanches and the public. People who venture into backcountry avalanche terrain literally make life and death decisions. They base those decisions partly on critical avalanche information from the Utah Avalanche Center, so we take our jobs very seriously. We often think of ourselves as natural detectives. We gather as much information as possible from a wide variety of sources, and then communicate our analysis to the public. We look at the weather, talk to ski area avalanche control programs, helicopter ski companies and highway control programs and volunteer observers on a daily basis. Our most important source of information comes from our own observations. We regularly travel into the mountains, where we can be in intimate contact with the snow. Doing field work in uncontrolled backcountry avalanche terrain is not only where we get our best information, but it's also where we can get instant feedback.

We split our time between the field, the office and education. With a staff of six people covering northern Utah, we have a rotating schedule in which one person sits in the driver's seat in the office as the forecaster for the day while the others either head into the mountains to look at snow, work on various special projects, teach classes, or take their scheduled days off.

Field day

A typical "field day" might begin at 6:00 in the morning when we wake up and immediately get on our home computer and look at the data from the automated mountain weather stations. We check the latest avalanche observations and our own avalanche advisory to get the information that helps us decide where to go for the day. After clearing our plans with the office, we jump in the car or on the bus and head for the mountains.

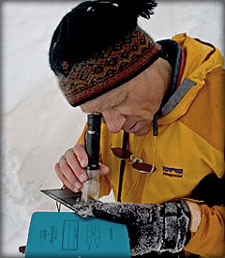

We conduct our fieldwork in the backcountry outside of controlled ski area boundaries. We put climbing skins on our skis and huff-and-puff to the top of a mountain, take off the skins, ski down into another valley, put the skins back on again, go to another ridge, and so on. We use snowmobiles to access more remote areas. We travel with a partner and carry avalanche safety equipment like electronic avalanche beacons, shovels, probes, belay rope, cell phones and Spots. We seldom have a regular patrol area; we simply go to the area that concerns us the most, or to a place that we know is representative, where we can look at snow on a variety of aspects, elevations and terrain types.

We gather information in many different ways. For instance, we dig snow pits on many different slopes to get a good feel for the distribution pattern of snow stability. A snow pit is about a 5 foot (1.5 meter) hole in the snow; we do a variety of stress tests on snow in the pit to determine the stability of the overall snow pack (click HERE for an overview of snow pit techniques). We also look at the crystallography of the various layers, temperatures and we document this information in a snow profile. Though these tests might sound complicated or time-consuming, we usually spend no more than 15 minutes in a single snow pit. We would rather dig several quick pits in several areas than do one detailed pit in one area because we want to know the distribution of the pattern. Once we figure out what kind of avalanche dragon we're dealing with, we can communicate it to the public.

We also jump on small test slopes, drop cornices, perform safe slope cuts, and visit recent avalanches to identify the weak layers and gauge how reactive they are. We keep close track of the pattern of recent avalanches, and we always pay very close attention to the present snow surface because it's much easier to map a layer of snow when it's still on the surface than after it's buried by the next storm.

Once we get home, we head to the computer, and create a detailed observation, often including photos, snow profiles and/or videos, which we post on line. We also may contact the next day's forecaster to discuss the current conditions in more detail, making sure not to call after 8:00 pm, because they have to be up by 3:00 AM the next morning.

People always ask if it's dangerous. We don't normally think of it as being dangerous but, like driving on the freeway, it certainly can be dangerous if you don't know what you're doing. It takes quite a bit of training and experience to be able to travel safely in the backcountry and several years of experience and training to be an accomplished avalanche forecaster. Some of our staff have degrees in physical sciences such as meteorology, geology or engineering. Some have several years experience doing avalanche control at ski areas or mountaineering backgrounds, and most have traveled through out the west, looking at, recreating and teaching avalanche classes in a wide variety of snow packs.

Office Day

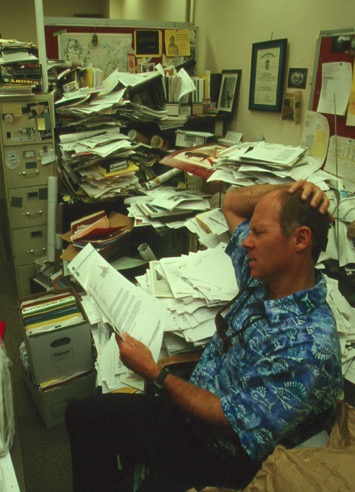

We usually arrive at the office around 4:00 am, sometimes earlier on big storm days. There's only one avalanche person in the office, which is co-located with the National Weather Service near the Salt Lake Airport, so the pressure and time constraints are intense. First, we check for backcountry field observations on the computer, the answering machine and by e-mail, not only from our staff, but from the army of volunteer observers, ski areas, helicopter skiing companies and highway control programs that contribute to our advisories. We then furiously kick into high gear and write backcountry avalanche advisories customized for three different zones (Ogden, Salt Lake and Park City, and Provo), record an the info on our 1-800 line, record 2 pod casts, and do two live radio interviews, all while trying to answer the phone from ski areas calling to leave observations or talk about avalanche hazard. All this activity is mirrored by the Logan, Western Uintas and Skyline forecasters.

The recorded advisories are on by 7:30am, when we're done with the last live radio interview, we finally collapse with relief, take that bathroom break we've wanted for the last couple hours and take a walk outside and watch the sun rise and hope that our information is accurate because an average of 800 people call the avalanche recording and over 13,000 access the website before heading into the backcountry to test our analysis with their lives. We send a custom emailed forecast to another 3500 each morning.

Then, when most people are eating a late breakfast, it's lunch time. After lunch, we start answering phones, collecting data, updating content on our web sites and just catching up. Then we head home and get some sleep. Later each evening, we are all back on the computer for several more hours, updating as much information as possible each evening, allowing the next day's backcountry recreationist a 10 hour head start in their information gathering. Meanwhile, the rest of the staff is out in the field, looking at the snow so the UAC can do another advisory the next day.