Chris Benson

It has been said that all models are wrong, but some are useful. Back in October, many models predicted that the 2020/2021 winter season would be impacted by a moderate to strong La Niña event.

As of early January, these aberrantly cool sea-surface temperatures in the east-central Pacific Ocean are delivering on their premonitions.

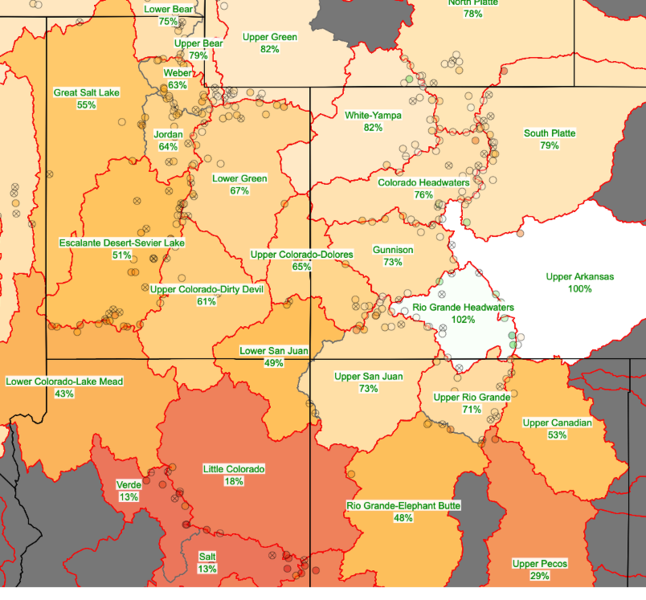

As early 2021, much of the Four Corners region is experiencing below-average precipitation.

Low amounts of snowfall and cold temperatures produced myriad weak layers throughout the region from October through late December. This pattern changed during the last week of December, when a strong closed low approached the region.

Looking southwest towards the east face of the Abajo Mountains on 12/27/2020 (aerial photo by C. Benson).

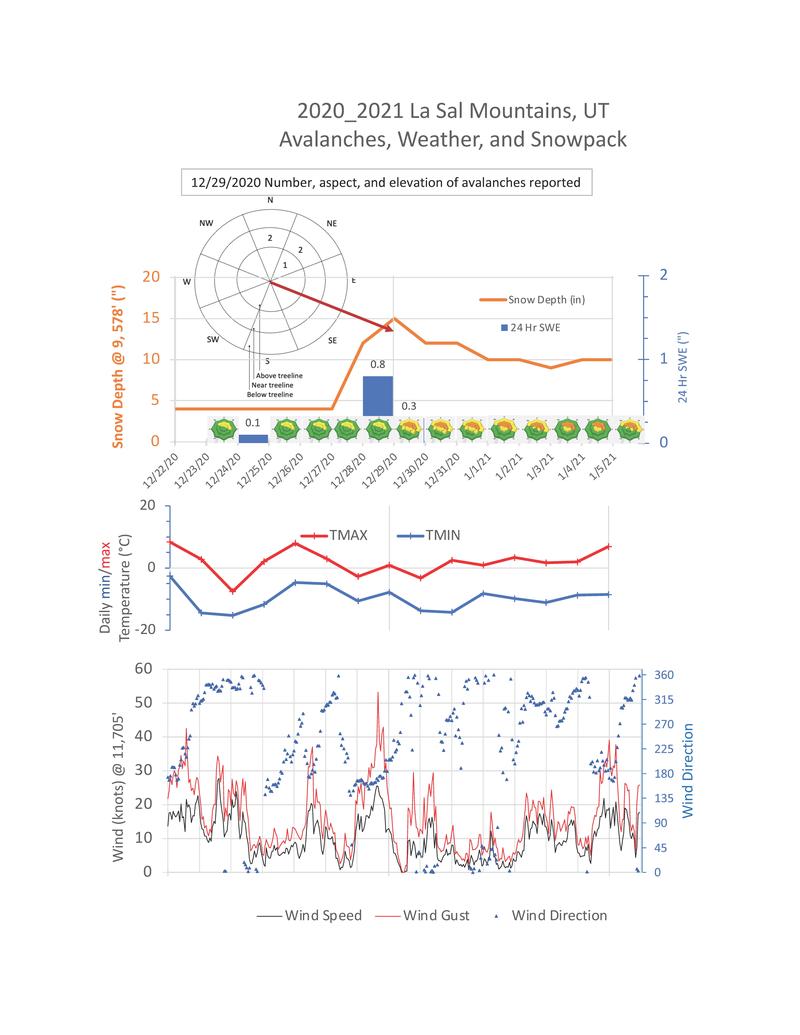

The December 27-29th storm snow fell on a variety of surfaces, ranging from snow-free slopes, to slopes with faceted snow, to slopes with facets and crusts.

Note the bare slopes on east and southeast aspects. Northeast and north aspects harbor weak snow layers from previous weather conditions.

Looking northeast towards the La Sal Mountains on 12/27/2020 (aerial photo by C. Benson). Note that most south-facing slopes had little to no snow.

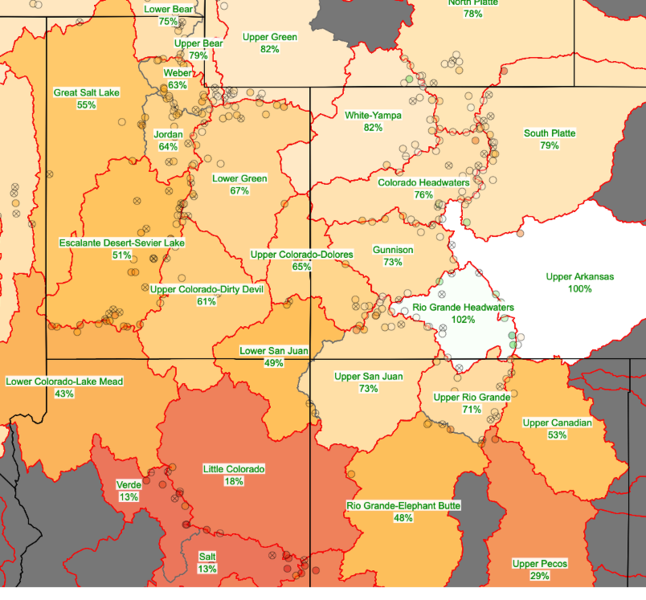

A snapshot of the atmosphere at around 18,000’. The closed-low-pressure system over the coast of California shows strong lift through a parameter called absolute vorticity.

What does this mean in terms of snow and avalanche conditions?

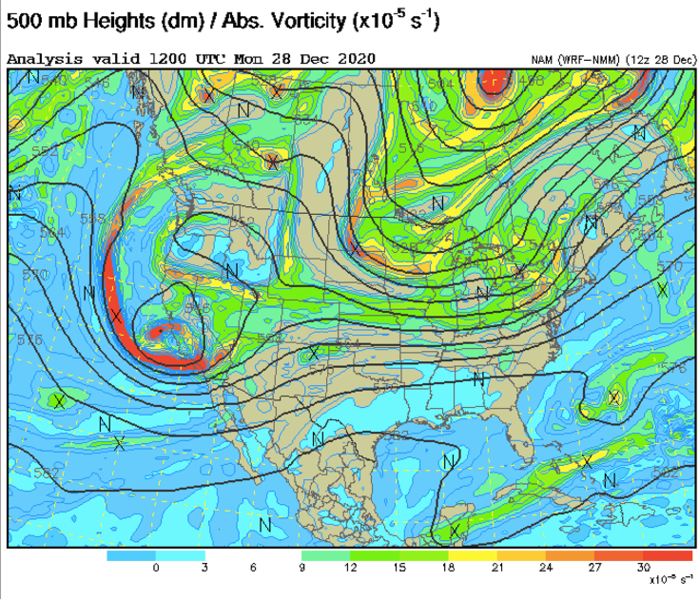

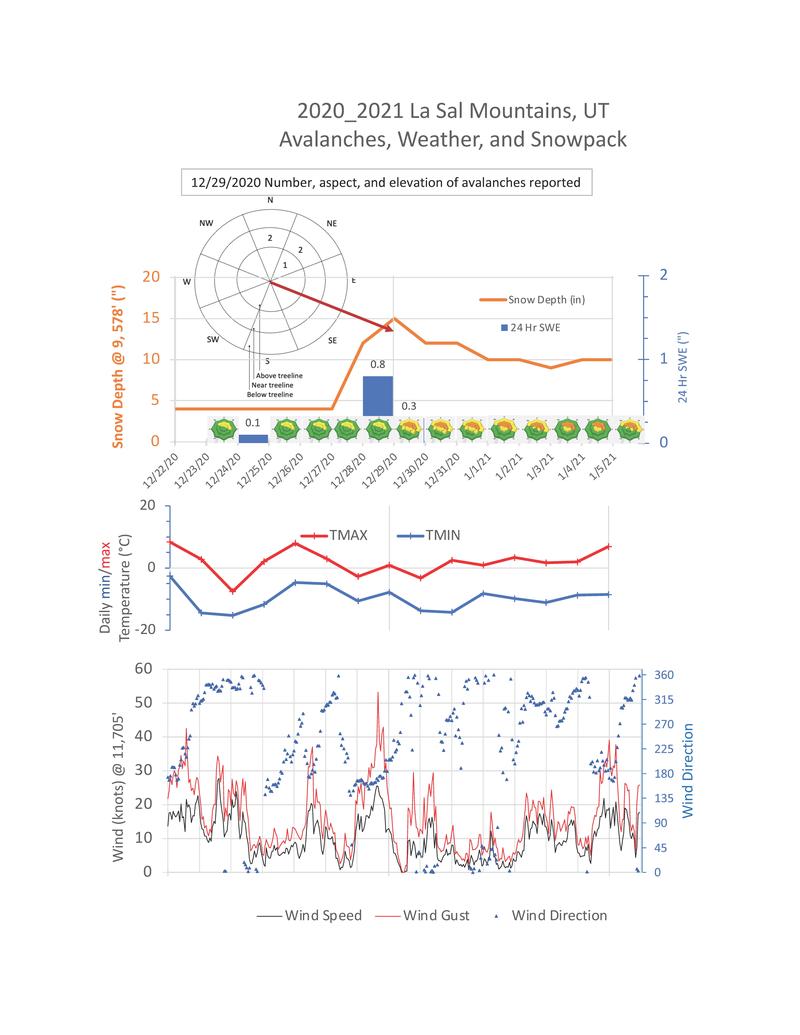

This storm resulted in about 1.1” of snow water equivalent (SWE) at the SNOTEL site near the Geyser Pass Winter Trailhead.

Various reports of 10-20” of snow at higher elevations from 12/29/2020 were received.

During the storm, moderate to strong southerly winds transported snow near and above treeline, resulting in additional loading on northerly aspects.

The first observed avalanches in the La Sal Mountains for the 2020/2021 season were noted on 12/29/2020.

Roughly five, D1 to D2 -sized, naturally occurring avalanches were documented on north and northeasterly aspects.

These probably ran sometime in the afternoon or night of 12/28/2020 and represent only a portion of similar avalanches across the range.

It will be important to note where these avalanches have occurred as they will probably become “repeat offenders”.

This is in part due to the fact that these areas now have a relatively shallow snowpack, and with cold temperatures, the remaining snow will continue to loose strength. If and when we recieve more snow, these areas will have a poor snowpack structure.

Although we have not had much precipitation so far this season, don’t let your guard down.

In fact, these conditions warrant extra caution because the various persistent weak layers will continue to “wake up” each time we get an additional load in the weeks and months to come.

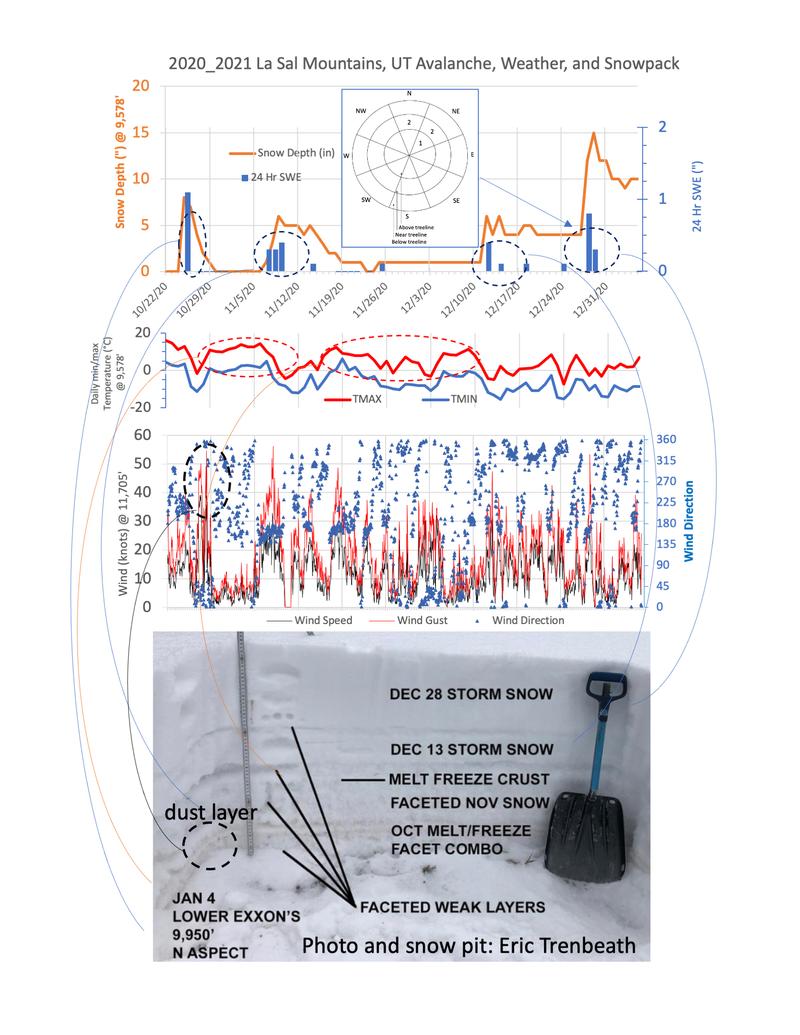

To help you know what to look for in your snowpits, and make more-informed decisions, here is season-long look at both graphical data, and what that looks like in a snow pit.

This will help you to identify these dangerous weak layers in our complex snowpack.

In general, northerly slopes that have had snow since late October are the most suspect. In contrast, southerly slopes that do not harbor old, rotten snow on top of melt freeze crusts are in general, lower risk in terms of avalanches, but are probably shallow and present many early-season hazards.

On one final note, several observers have noted surface hoar while touring and even buried-surface hoar in their snow pits.

This thin, feather-like weak layer may cause issues in our current snowpack and if buried by the next snow, could add to our weak snowpack structure.

One thing to remember is that if you are seeing surface hoar you are in a location favorable to its formation, and thus, there may be buried surface hoar lurking below the surface.....

Photo by Maggie Nielsen.