Mark Staples

2015-2024 - Director, Forest Service Utah Avalanche Center

In the winter of 2016-2017, a quarter of avalanche fatalities in the US were solo travelers. Having a partner to perform a rescue is a fundamental part of avalanche safety. We decided to look at other winters and see how many people in the US were dying solo.

The initial focus on solo avalanche fatalities brought to mind a handful of snowmobilers where the victim had left the group and was alone at the time of the avalanche. How often was this an issue with skiers and other user groups? What other situations were there when an avalanche victim with partners was “effectively solo?” How often are your partners in a good position to rescue you?

We ended up defining “effectively solo” as situations when you have a partner who can’t perform a fast, efficient rescue because they are:

(1) Out of sight

(2) Too far away

(3) Also caught in the avalanche

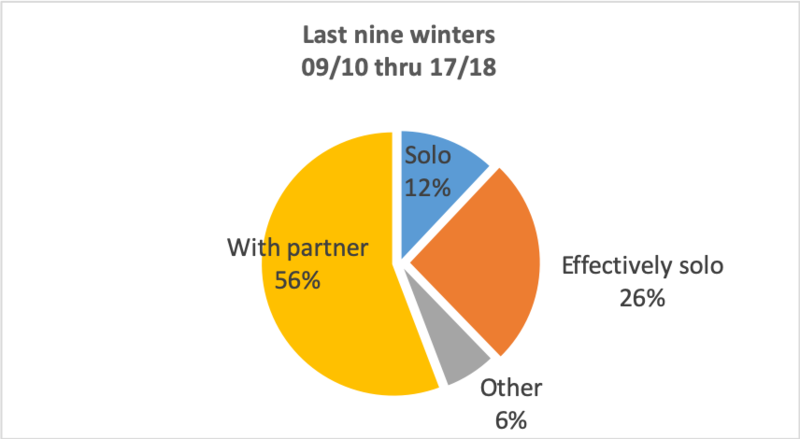

The numbers from the 15/16 and 16/17 winters shocked us so much that we decided to examine eight winters of solo and effectively solo avalanche fatalities as well. Below are the results for both data sets.

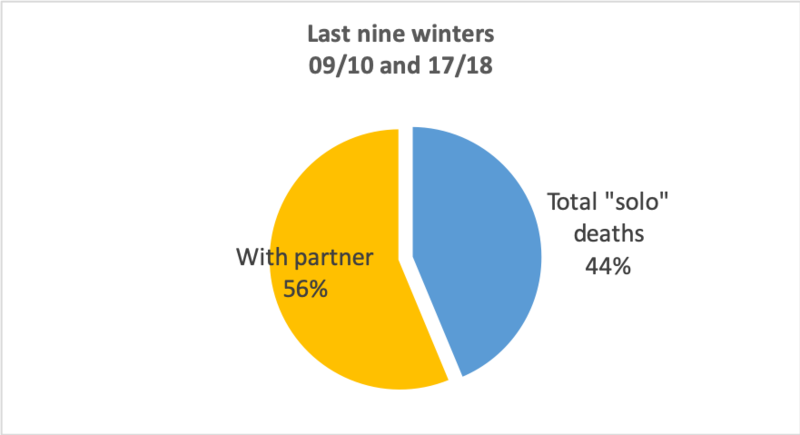

Five out of 10 were effectively solo. In the 15/16 and 16/17 winters, 54% of people killed in avalanches were either solo or effectively solo. Looking back over nine winters, 44% were either solo or effectively solo. Some of these victims would have died regardless, due to trauma, but a partner could have made a difference. An effective partner might have dug them out alive. A partner might have stopped the bleeding or taken some other life-saving measure. In a few cases the victims survived the avalanche and were conscious. More importantly than performing a rescue, a good partner may have also questioned the original decision to get on the slope that slid.

Evelyn worked with two other people to study how many folks were dying while traveling uphill. The results were surprising. Read more about avalanche fatalities during uphill travel here.

Outside Magazine wrote a great article on these topics worth reading. It can be found here.

The charts below show how the numbers break down for 9 winters. The Yellow wedge is all the people who died and had a partner nearby, but the person died anyway. The blue wedge is all the people that were traveling solo and had not parter available. The orange wedge is all the people who died that had partners but the partners were not able to reach them in a timely manner due to one of the three conditions listed above. The grey wedge is all the people who died and were kind of effectively alone but did not fit the definitions we outlined. These were cases sometimes involving climbers roped together, climbers sleeping in a tent, or other scenarios when no one was available to perform a timely rescue.

The second pie chart combines the blue, orange, and grey wedges for simplicity.

Greats stats. This is really helpful for the discussion on traveling solo, and more so the concept of an effective partner. While having both you and your partner caught in a slide makes you effectively solo, the one item that is missed (I think) is if there were deaths where the partner was not buried, but did not possess the rescue skills to save the buried skier. There are lots of good discussions about terrain decisions when setting out to ski tour solo, but not so much about terrain decisions when you know (or think you know) that you are heading out with a partner who does not practice with rescue gear and is not efficient with it. Then again, maybe making more risky terrain decisions because you think your partner ‘is’ efficient with partner rescue is a concern in of itself possibly falling into the Expert Halo heuristic trap.

John Adams (not verified)

Sat, 5/16/2020