Observer Name

Jason Wooden sent in the story by Author, Nolan P. Olsen

Observation Date

Thursday, January 23, 2025

Avalanche Date

Thursday, February 26, 1880

Region

Logan » Logan Canyon » Logan River below Temple Fork

Location Name or Route

Logan Canyon, Dugway Area, below (south) of Temple Fork Junction

Elevation

6,100'

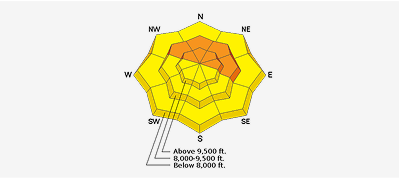

Aspect

North

Slope Angle

Unknown

Trigger

Natural

Avalanche Type

Wet Loose

Avalanche Problem

Wet Snow

Weak Layer

Wet grains

Depth

Unknown

Width

300'

Vertical

600'

Caught

7

Buried - Partly

5

Buried - Fully

2

Killed

2

Accident and Rescue Summary

Seven men, sawmill workers with two horse teams, were hit by a large avalanche in Logan Canyon as they approached the Temple Fork Sawmill on February 26, 1880. The story is told in the the book, "Logan Temple, The First 100 Years" by Nolan P. Olsen.

Comments

"Logan Temple, The First 100 Years" by Nolan P. Olsen, pages 76-79.

Logan Temple The first 100 years by Nolan P Olsen

Tragedy Strikes

February of 1880 was a snowy month and the white stuff was piled high. The local brethren were anxious to be at work at the sawmill, so on February 19, a group of them left Logan in a heavy snowstorm. They arrived at Wood camp, two thirds of the way into the canyon, where the road was closed and they were snow bound until the 26th.

The following morning dawned with a fair sky. “At an early hour all hands were at work again shoveling snow and otherwise clearing the road of slides and drifts that had formed.” Seven men, with two mule teams belonging to the temple, and one privately owned horse team, pushed ahead. When they had nearly reached the mouth of the fork, a huge snow slide came down upon them, burying the whole party and animals. The slide had come a distance of 750 feet and was 300 feet wide at the base, and was in the shape of the letter “V”. Five of the men were able to extricate themselves and were uninjured, but the animals and two brethren were buried deep.

William L. King. aged 25, was one of the chief teamsters who hauled logs out of the canyon. He had a wife and a child, and the men said he could sing and tap dance, and it was not uncommon for him to entertain the men by dancing on the tables at the mill camp. The other teamster was Nephi Osterholdt, a quiet man about 25 years from St Charles, Idaho.

Charles O. Card and Nathaniel Haws had remained at Wood Camp to make some repairs and do other chores, and then followed the men up the canyon. He says; “At 3:40 p.m. we had reached a point about a half mile below Twin Bridges. At this time David Beech and James Stratton arrived with the information about the tragedy, about three and one-half miles from where they were working. I immediately started to the rescue with six men, and dispatched a messenger to Logan for assistance. We arrived at the slide at 6:30 and found the other men doing all they could to extricate their companions. We labored frantically until 9:30 p.m., when all hands were fatigued and worn out. We arrived back at camp after midnight, had supper, and laid down to rest, but the circumstances of the day, together with the hard grilling labor made sleep impossible.”

The messenger arrived in Logan about 11 p.m. to find an extra lively dance in progress at Logan’s dance hall. “Siv” Jeppson’s orchestra was furnishing the music with a piano, two violins, a bass viol, and two horns. There was a large crowd and everyone was enjoying quadrilles, lancers, shotische, and polkas. “The waltz and other types of dancing were endured by some as a mild form of wickedness, but were certainly not encouraged.”

Just before intermission time a man in a heavy coat hurried in from outside and walked past the dancers to the man in charge, addressing him in an agitated manner, which drew the attention of the dancers. A hush fell over the hall as the announcement was made that Billie King and Neph Osterholdt were buried in a snow slide, and all the men were needed to go dig them out. There was only a moment of excited conversation and the men began hurrying for their coats and hats. Tears stood in the eyes of the ladies as they hurried to help the men get ready. The orchestra packed their music and instruments, and the hall was empty within minutes.

Messengers hurried to the homes of old canyon workers to spread the call for help. Magnus Holm hurried from the dance to the temple stables and put hay and other provisions in the sleighs, and it was not long until several outfits were on their way, followed by many others.

Digging for the men under the snow slide began at day break on the morning of the 28th. Water had backed up from four to eight feet deep and saturated the slide, freezing it solid. Working was very dangerous, with the threat of another slide. During the day two of the teams were found, and a roadway had been opened around the other side of the slide, so the weak lame and exhausted could ride to the mill. The search continued well into the night, but was fruitless.

On Sunday the 29th, the weather turned warmer during the night, and the river cut its own channel under the slide and drained the snow dry. This permitted the digging and search to be resumed with vigor. After some time the other team was found, and at about 10 a.m. the body of Brother King was found prone in the bed of the river. They said he had tried to get on the crest of the slide by standing on the backs of the team. His body was put on a sleigh and sent to Logan.

About an hour later the body of Brother Osterholdt was found crushed against the bank of the river, with upraised arms holding a shovel in both hands, with one knee raised as if he were trying to climb the bank. When they saw the slide coming and could not get out of the way, Osterholdt tried to reach the opposite side of the river, when he was caught. His companion David Beech managed to ride the crest of the slide amd was carried across the creek and quite a distance up the opposite bank. The searchers headed back to Logan with the body of Osterholdt. A terrific blizzard came up and the party had trouble arriving in Logan that evening. They said it was the worst storm they had ever experienced in a lifetime, and the road was entirely obliterated.

William King’s father was one of the searchers, and that night and day he paced up and down, wringing his hands, exclaiming in his best Scottish brogue: “Me son Billie’s a guid boy, but he’s got a cauld, cauld bed tae nicht.” he was so stricken with grief that he could hardly contain himself.

In town the tragedy was the chief topic of conversation wherever people met. All day Saturday and Sunday groups of women and girls and a few men could be seen trudging through the snow from their homes in the Fifth Ward to the brow of the hill to look down on the canyon road for the return of the searchers. They would stand in the snow and chill wind for a few minutes and sadly pull their shawls closer and trudge back. The whole community was in mourning and a great sense of loss pervaded their hearts.

Two homes suffered a great sorrow, and every one in the valley mourned the loss of these two good men who were too eager to get the Lord’s work under way. Their funerals were held together in the Tabernacle on March 2, with 1,500 people assembled to pay their respects. Forty-three vehicles were in the funeral procession as the bodies were taken to the Logan cemetery for burial.

The temple masons made monuments with sandstone from the Franklin quarry, which still stand in the Logan cemetery, but the inscriptions on the stones are so worn that they are hardly legible today.

This tragedy struck deep into the hearts of the temple workers, and thereafter they had more respect for the Logan canyon snows of winter.

Coordinates