Observer Name

Bruce Tremper, Hardesty, Meisenheimer

Observation Date

Friday, April 12, 2013

Avalanche Date

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Region

Salt Lake » Big Cottonwood Canyon » Kessler Peak » Kessler Slabs

Location Name or Route

Kessler Peak - Kessler Slabs

Elevation

9,900'

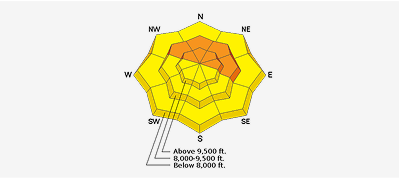

Aspect

East

Slope Angle

45°

Trigger

Skier

Avalanche Type

Soft Slab

Avalanche Problem

Wind Drifted Snow

Weak Layer

New Snow/Old Snow Interface

Depth

8"

Width

45'

Vertical

1,500'

Caught

1

Carried

1

Killed

1

Accident and Rescue Summary

This is a preliminary avalanche accident report and we will add additional information and videos to it as time allows. Please contact Utah Department of Transportation for all media inquiries.

Quite a large group of people went in together to investigate the avalanche. There was 5 Utah Department of Transportation forecasters including Chris Covington, Matt McKee, Bill Nalli, Adam Nesbitt and Steven Clark. From the Forest Service Utah Avalanche Center there was Drew Hardesty, Trent Meisenheimer and myself (Bruce Tremper) totaling eight people.

The victim was Craig Patterson, a forecaster for the Utah Department of Transportation Snow and Avalanche Program, which forecasts and controls avalanches for both Big Cottonwood Canyon and Little Cottonwood Canyon. Craig was doing fieldwork alone on Kessler Peak to check out the snow stability conditions, because avalanche slopes on Kessler Peak can threaten the highway below.

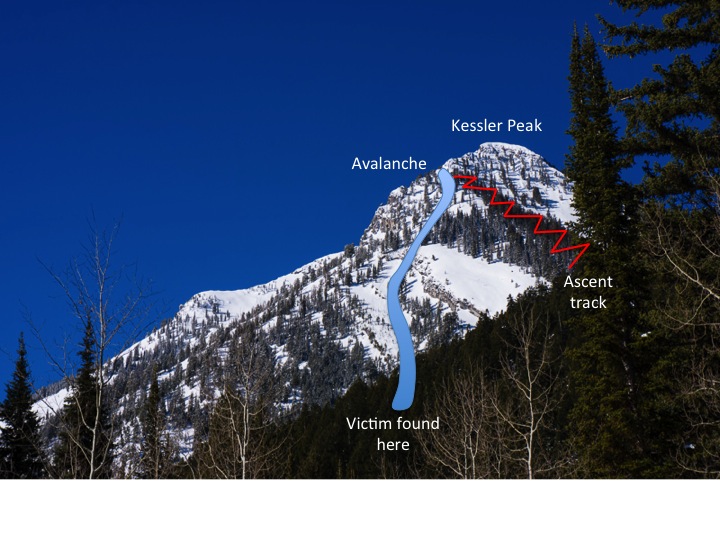

Craig followed a fairly standard up-track used by both public backcountry skiers and by UDOT forecasters, which utilizes a thickly-treed ridge between avalanche paths locally known as God's Lawnmower, which is just west of the ridge and Kessler Slabs, which is just to the east of the ridge. He ascended the ridge using climbing skins and made switchbacks up the northeast-facing ridge. As he neared the top of the ridge where he presumably planned to descend back down the ridge he ascended, his ascension track led around a corner from the northeast-facing ridge onto a steep, east-facing slope where he presumably triggered the avalanche that killed him. The flank fracture of the slab was directly on the sharp ridge that divided the safer snow on the northeast facing slope from what appeared to be recently wind loaded snow on the east facing slope. The distance of only a foot or two separated safe snow from dangerous snow. It's uncertain whether he was planning to make another switchback to stay on the safer north facing side and just stepped around the corner too far or whether he planned to continue onto the east facing slope to examine the snow there.

The avalanche was a relatively small wind slab, about 6-8 inches deep (a foot deep in the deepest section) and about 45 feet wide. It was on a very steep slope, which was 50 degrees at the crown face and 45 degrees where his track led across the flank wall of the slab fracture. It's likely that the avalanche broke 40' above him as he stepped onto to the recently wind-loaded slope. The avalanche path descends through many sparse trees and over a couple cliffs. The avalanche swept him 1380' vertical feet down the slope where he came to rest on the surface of the debris with his avalanche airbag deployed.

He checked in by phone around 1:00 or 1:30 in the afternoon when he was high on the mountain and reported stable snow conditions. He failed to check in later in the day nor return home that evening so the authorities were notified. His UDOT truck was still parked at the Cardiff Fork trailhead. A Life Flight helicopter was able to fly just before dark to search for him and they noticed the avalanche with a person on top of the debris and not moving, but the terrain was too steep to land. Ground-based rescuers from Wasatch Backcountry Rescue under the command of Salt Lake County Sheriff accessed the area on foot after dark. They found Craig's body on the surface of the debris with his avalanche airbag deployed and obvious trauma to his head and hip with rips in his pants. He was obviously still in "uphill mode" as he will had a climbing skin on his ski (the other ski was missing) and he was dressed lightly. He was laying head downhill and on his side. His body was only about 50' vertical feet above the toe of the debris.

View of the accident site from the Big Cottonwood Canyon road. The victim followed a standard climbing track up the northeast facing, densely-treed ridge and on his top diagonal, he crossed around a corner onto an east facing slope and triggered an avalanche, which descended down a different drainage than the one he ascended.

This is the site where the victim was found on the snow surface with his avalanche airbag deployed. He was located where the person in the shadows is standing, which is about 50 vertical feet above the toe of the avalanche debris.

This is the site where the victim was found on the snow surface with his avalanche airbag deployed. He was located where the person in the shadows is standing, which is about 50 vertical feet above the toe of the avalanche debris. The victim's tracks are presumably the ones in the bottom of the photo and they lead into the flank wall of the avalanche he probably triggered. It's unknown whether he was doing another switchback and strayed too far onto the steeper, more east-facing slope or whether he intended to examine the snow there. The avalanche was a wind slab that was only about 8 inches deep and 45 feet wide but it was enough to catch him and sweep him down the steep slope.

The victim's tracks are presumably the ones in the bottom of the photo and they lead into the flank wall of the avalanche he probably triggered. It's unknown whether he was doing another switchback and strayed too far onto the steeper, more east-facing slope or whether he intended to examine the snow there. The avalanche was a wind slab that was only about 8 inches deep and 45 feet wide but it was enough to catch him and sweep him down the steep slope. Looking down the slope, which is quite steep--45 degrees where he stepped onto the slope and 50 degrees at the crown face. It drains through many sparse trees and over a couple cliffs on the way down.

Looking down the slope, which is quite steep--45 degrees where he stepped onto the slope and 50 degrees at the crown face. It drains through many sparse trees and over a couple cliffs on the way down. Looking downhill, you can see his ascent track on the left of the photo coming up towards the camera. He ascended the gentler, northeast facing slope and then crossed over a divide in the center of the photo onto a steeper, east facing slope on the right of the photo (where the avalanche occurred) that had different snow characteristics due to the different aspect with respect to wind and sun.

Looking downhill, you can see his ascent track on the left of the photo coming up towards the camera. He ascended the gentler, northeast facing slope and then crossed over a divide in the center of the photo onto a steeper, east facing slope on the right of the photo (where the avalanche occurred) that had different snow characteristics due to the different aspect with respect to wind and sun.Terrain Summary

The slope where the avalanche occurred was very steep--50 degrees at the crown face and 45 degrees where his track led onto the slope. The slope continues at around 45 degrees and strains through many sparse trees and at least two ~ 10' cliffs. With so many obstacles, it would have been unlikely to survive an avalanche on that slope. The slope is east facing with the crown face at 9921' and the bottom edge of the debris at 8540'. The starting zone is slightly bowl-shaped, about 50' wide and it obviously collects wind drifted snow both from north and south winds.

Weather Conditions and History

I will fill in the details here later, but basically there were two snowstorms accompanied by wind in the 5 days previous to the accident that deposited new snow on top of a pre-existing sun crust. Most of the snow had stabilized but there were lingering pockets of wind slabs and rapid warming on sun exposed slopes exacerbated the instability. Thursday - April 11's quick storm deposited 4-8" in the morning with gusty northwest winds along the high ridgelines. Intermittent midday sun and increasing temperatures (rising to 30 degrees at a representative weather station at 9880' in Big Cottonwood Canyon) may have accentuated the sensitivity of the wind slab.

Snow Profile Comments

Most of slope avalanched so there was not much of a crown face or flank wall left to examine. But from what we found, we all agreed the slab was composed of wind drifted snow, which slid on the sun crust, which was about 6-12 inches below the snow surface. In some places there appeared to be some weak snow on top of the sun crust--perhaps radiation-recrystallization crust, and on one flank there was obviously a small patch of faceted snow under the slab. I suspect that most of the slab simply slid on the interface between the new, windblown snow and the ice crust.

We did not notice any unstable snow conditions on the ascent route. We assumed that the winds from the northwest the previous day and the morning of the accident had drifted snow onto the east facing slope where the avalanche occurred.

The Utah Avalanche Center avalanche advisory rated the danger as Moderate for localized wind slabs and for wet avalanches from rapid warming.

Trent Meisenheimer, Drew Hardesty and I are examining the fracture line of the avalanche to determine the snow structure. UDOT avalanche forecasters are coming onto the slope below to also examine the snowpack.

Trent Meisenheimer, Drew Hardesty and I are examining the fracture line of the avalanche to determine the snow structure. UDOT avalanche forecasters are coming onto the slope below to also examine the snowpack.Comments

After seeing the accident site and the avalanche conditions, we all agreed that it was the kind of accident that could have happened to any of us. In the mountains, sometimes the snowpack can vary dramatically with subtle variations in terrain and only a step too far can have huge consequences. It was a sad day for all of us to lose a friend, a co-worker and such a wonderful person.

The accident was especially tragic because the victim, Craig Patterson, was not only a skilled forecaster but he was widely loved and admired. He was, smart, a great public speaker and teacher and one of the finest human beings most of us had met. Most tragic of all, he left behind a wife and a 6-year-old daughter.

Special thanks to Wasatch Backcountry Rescue and Salt Lake County Search and Rescue for their hard, and sometimes dangerous work. We are all very lucky to have such a great rescue team.

Final note: since he appeared to die from trauma and he was on the snow surface, having a partner with him probably would not have changed the outcome of this accident. As one of the rescuers noted, "It was a small avalanche but a really bad ride."

Coordinates