The following blog post is by guest author, UAC observer, and Wasatch Backcountry Alliance vice president Tom Diegel. This post is not intended to represent official opinions of the UAC. Instead, it is to offer a starting point for constructive discussions and thoughts about how to recreate during the current health care crisis. The State of Utah has information about outdoor recreation posted HERE.

COVID19. It’s real, and real scary. Got it. But I, probably like you, am already weary of hearing about it. However, regardless of how weary I am of COVID19, it doesn’t matter: this will be something that will last for not just weeks, but for months and possibly years, and the social effects it will produce may last for a generation. But will these affect our recreation, and in particular, our willingness to assume Risk?

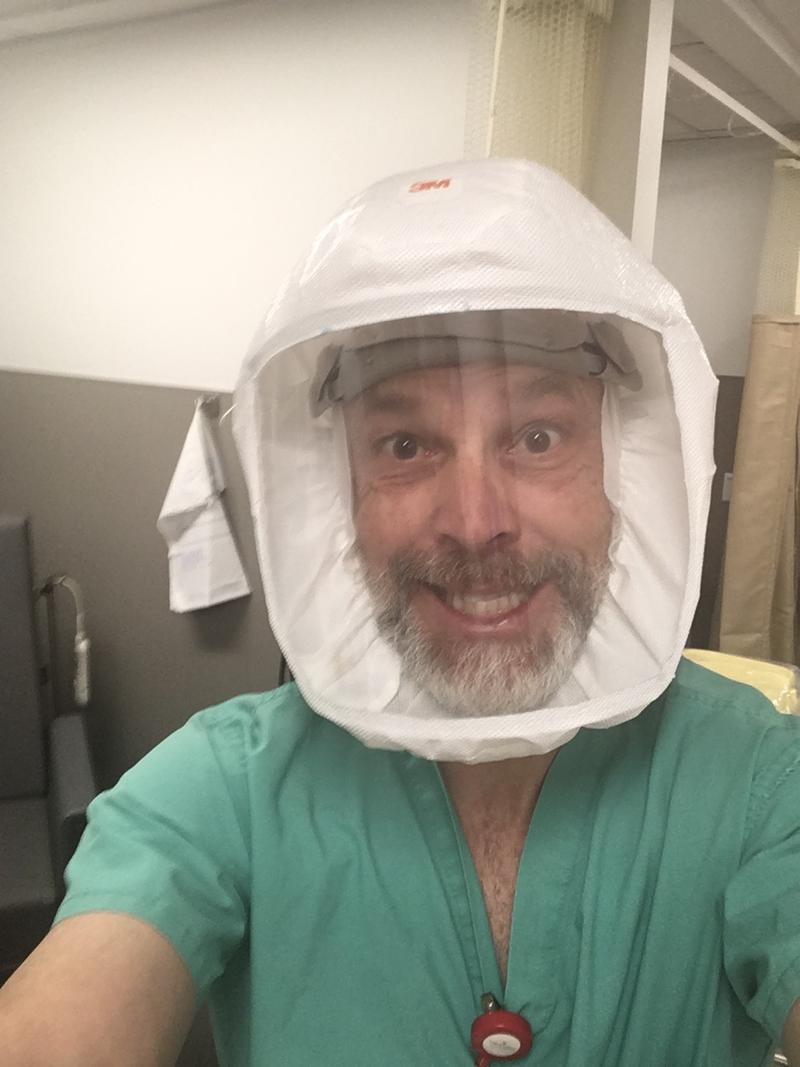

Photo - Having fun or risking it all?

I have been thinking about Risk a lot this winter, regardless of The Corona Plague. Specifically, I gave a lot of thought to the concept of Risk Tolerance, specifically as it has to do with skiing in avalanche terrain. Drew Hardesty of the Utah Avalanche Center did a great podcast interview this winter with two very smart and fascinating characters (whom I am fortunate enough to call friends): The Economist and The Weatherman (who walk into a bar) who – among other fascinating topics – discussed the concept of risk as it relates to uncertainty. Peter Donner (retired state of Utah economist) and Larry Dunn (retired director of the Utah National Weather Service office) had surprisingly never met (despite both being longtime Wasatch skiers) and despite their different backgrounds and perspectives, combined to make a fascinating conversation. Among many points, Peter made the great one that Risk and Uncertainty are two very different things, yet are strong bedfellows: Uncertainty is the likelihood of any given outcome to occur (or not), and Risk is a willingness to assume the effects of that uncertainty of outcomes. So “Risk Tolerance” is really an indistinct measure of our willingness to deal with the implications of an uncertain outcome.

When we ponder our decision to ride any given slope, we use the tools that we have developed (whether we are a newbie with no experience, a recreational backcountry rider who’s taken a level 1 class, a pro, or any level in between) to attempt to determine the likelihood of the slope to avalanche. With more experience come more tools, of course. Our understanding of the details and implications of the relationships between weather/wind, elevations, slope angles, aspect, terrain features, makes up our toolbox of knowledge.

Then there’s the decision point: ride the slope or not? Even with a lot of knowledge, uncertainty still remains: we don’t know if it’s going to slide or not, if we do rip it and it doesn’t slide we don’t know if we got lucky or not, and if left untouched we’ll never know. And yet we push off a lot onto lot of runs, thus we are willing to assume The Risk of the implications of this uncertain outcome, and those implications can be severe: broken bones, head injuries, internal injuries, hypothermia awaiting rescue, and death. Even if you are lucky and end up intact on top, just ask anyone who’s been in an avalanche and they’ll tell you their tale that will be peppered with words like “terrifying”, “uncontrollable”, “panicked”, “death”, “sorrow”, “desperate”, “humbling,” etc.

Ideally, the decision to ride a slope or not is a function of reducing that uncertainty: based on what we know, we generate a level of confidence in our assessment of stability. Our Risk Tolerance is our willingness to take action based on that confidence, as well as a function of our perceived ability to deal with any potential negative outcomes. I have a friend who’s taken a level 1 class and has skied a fair bit in the backcountry, but she still lacks confidence to the point where she is perpetually scared of avalanches almost regardless of the conditions/terrain. She is unable to assume the risks associated with any level of uncertainty. On the other hand, there are many people who consistently ride terrain that the avalanche forecasters have indicated has a higher likelihood of avalanching. So those people are willing to assume the very same potential negative outcomes (ie risks) of humility, terror, panic, injury, death etc that are associated with that uncertainty. And do so simply for the sublime sensation of riding wild snow.

Of course, there are also the non-avalanche injury risks associated with winter adventuring that can at best ruin your day and at worst put you into the health care system. I have many friends who have blown ACL’s just skiing along, and just several weeks ago a notable member of the community with many years under his belt was paralyzed and scalped by clocking a tree on his exit at the end of a big ski day.

None of this is new; hopefully we all know and understand the uncertainty/risk/reward equation. However, the last few weeks has changed this mindset for a lot of people. With the advent of COVID19 there has been a lot of talk about backing off and reducing risk, ostensibly to avoid a) taxing a health care system that may soon be overwhelmed by virus sufferers, b) exposing potential health care providers to you, as a potential carrier, or c) exposing potential search and rescue (SAR) personnel to you and/or each other as potential carriers (there hasn’t been much talk of you - the selfish victim - becoming more at risk of infection from SAR personnel or health care providers). These are all legitimate concerns, because as many smart people have said: this shit is real, and people getting infected are not just the old and infirm. Utah Congressman Ben McAdams is a healthy, athletic, and vibrant 45 year old who spent 8 days in the hospital, lost 10 pounds, and now has noticeable lung damage. And health care providers who are supposed to be helping victims stay alive are more vital at this point than most folks, and we can’t afford to have them go down.

Photo - This guy can't wait for you to show up.

But should COVID19 affect our current judgment in the backcountry? Given that the implications of going for a ride in an avalanche can be quite severe, I would argue that your Risk Tolerance should not change now; it should be consistent with what you’ve done in the past and in the future. If it takes “don’t overstress or endanger our health care system” as the catalyst for someone to back off of a decision that has as much gravity as an avalanche accident represents, then perhaps that person should rethink their backcountry decision making process in general. Just as other inflection points, such as another level of avalanche class, an accident involving you or your friends, purchasing an avy pack, riding alone or with partners may have affected your confidence up and down over time, should/will COVID19 be another inflection point? Or to put it another couple of ways: next season, assuming that (hopefully) COVID19 is but a distant memory, will your avalanche terrain decision making process be any different? Or will you be more willing to risk breaking a femur or getting buried next season than you are today? Are you really not assuming risk of your own injury or burial or death today because you are worried about the effect on a potential rescuer or health care provider?

Photo - From a rescue recently in Bear Trap Fork, Big Cottonwood Canyon. Courtesy of SLCO Search and Rescue

It’s apparently easy for non-backcountry types – and these days, even many fellow backcountry enthusiasts - to angrily “ask” (declare): “Why are you even going out skiing! You need to stay home!” even as they drive their cars to the open grocery stores while conveniently ignoring the fact that 36,000 people in the US die in their cars every year, and grocery stores, gas stations, takeout pizza, and hardware stores are not conducive to social distancing and thus represent a far higher likelihood of infection than passing by each other on the skin track. And people continue to cut bagels in half, ride motorcycles, ride their bikes risking getting doored like a friend of mine did a month ago, take showers risking slipping in the tub, etc.

But these folks have a point: we all make decisions, and these days our decisions do potentially have a more profound effect on others, and our recreation that has historically been only to fulfill our own best self interests (ripping great lines in untracked powder) is now being put into a broader context of social responsibility, which resonates in these crazy days.

But when it comes to enjoying ourselves in avalanche terrain or in other “risky” activities, our decision making should remain consistent: we need to understand our decision making in an uncertain environment with unknown outcomes and acknowledge our willingness to assume the risks associated with that uncertainty, whether in the time of a global pandemic….or not.

Comments